China has been quietly involved in Africa for decades, but it is only recently that the relationship has taken on dramatic importance, both economically and politically

Fortunately, no one was injured when a $12 million bridge being built by a Chinese firm in Western Kenya collapsed before it was opened last June, though the incident was an embarrassment for Kenyan President Uhuru Kenyatta. Then campaigning for re-election on policies that included infrastructure development and Chinese partnerships, he had been to “inspect” the Sigiri bridge as part of his campaign only two weeks before.

Shortly afterward, the Chinese-built Nairobi-Mombasa rail project opened 18 months earlier than planned. The 470-kilometer (290 mile) line slashes travel time to four-and-a-half hours—half of the time required by bus—but the $4 billion price tag raised eyebrows. Critics claim the cost was inflated because the project was rushed for political purposes and now risks saddling the nation with monstrous debts to China for decades to come.

Although Kenyatta won re-election in August, the policy of Chinese engagement with Kenya’s economy is clearly being questioned. This stands in contrast to Ethiopia where a new Chinese-built railway, also costing $4 billion, links the capital city, Addis Ababa, to the port of Djibouti on the Arabian Sea.

With services still ramping up, the line promises to cut transport time between the two locations from three days to 10 hours. The hope is that Africa’s first fully-electrified cross-border line will at last provide access to global shipping lanes for Ethiopia just as the east African country is developing into a textile hub.

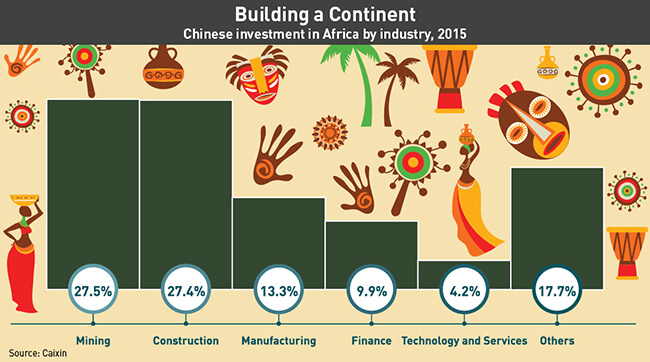

The two tales reflect the complexity of China’s expanding involvement in Africa. Total Chinese investment in the continent reached $3.5 trillion by the end of 2015, nearly seven times the 2007 figure. In the first six months of 2017, Chinese foreign direct investment (FDI) into Africa was $1.6 billion, up 22% from a year earlier, while imports from Africa jumped 46% to $38.4 billion, according to China’s Ministry of Commerce (MOFCOM).

Altogether there are around 10,000 Chinese firms operating in Africa, 90% of them private, according to a recent report by McKinsey. The same report also estimates that Chinese firms already handle 12% of Africa’s industrial production, valued at $500 billion a year.

But like high-profile infrastructure projects, private ventures can have mixed results, says Jilles Djon, Director of Operation at the Shanghai-office of the African Chamber of Commerce (AFCHAM). In the two years Cameroon-born Djon has held the position of AFCHAM’s Director of Business Operations, he has seen more individual Chinese entrepreneurs fail in Africa than succeed.

“Some cut corners by not paying for feasibility studies and some make the mistake of entering multiple African countries at the same time,” Djon says.

Successes, however, are impressive. In 2016, jobs created from Chinese FDI projects hit an all-time high of 38,400, more than double the number in 2015 and more than three times the number created by the next biggest investor, the US, according to EY (formerly Ernst & Young). More importantly, Chinese firms are bringing capital investment, management know-how and entrepreneurial energy, all of which are helping to accelerate the progress of Africa’s economies.

“In the past, China saw Africa only as a market for Chinese-made goods or a source for raw materials for the Chinese economy, but that has been changing amid different initiatives by the Chinese government to encourage companies to go abroad, such as OBOR [One Belt, One Road],” says Djon. “This, in turn, makes more Chinese private sector players willing to put up with the risks of entering the unknown.”

Depletion to Development

Africa’s 54 countries comprise an area more than three times the size of China, and Chinese interest varies enormously by geography. Companies engaged in resource extraction—mining, petroleum, timber—for export to China are concentrated in Angola, Congo, Guinea and Zambia as well as South Africa.

Manufacturers have been drawn to populous Nigeria and Ethiopia, on opposite coasts. Agricultural producers focus on Kenya. There also is considerable engagement north of the Sahara desert: almost a quarter of Chinese FDI projects in Africa in 2016 were in Egypt, according to data compiled by EY.

Over the last decade, the focus has moved from resource extraction and farming toward manufacturing. Benjamin Cavender, Associate Principal with Shanghai-based China Market Research, who has frequently visited Africa on behalf of international investment funds, attributes the change to several factors.

“Many companies have trouble manufacturing cheaply in China because wages have risen,” Cavender explains.

Another reason is that African countries’ have high import tariffs, especially on electronics. This makes Africa-based production more attractive. Owing to weak local supply chains, manufacturing focuses on assembly of imported parts of electronics, home appliances, vehicles, fashion and footwear in Ethiopia, Nigeria and South Africa, Africa’s largest markets.

Other drivers have been the devaluation of African currencies versus the RMB, as well as the EU’s extension of preferential treatment to exports from Africa compared to exports from China. Cavender also sees tremendous opportunity for growth in the local markets themselves, with Chinese companies tending to adapt to local needs faster than Western peers.

He points to Hisense, a Chinese home appliance-maker, as an example. The company designs refrigerators specifically for African needs by making the freezing temperatures much lower than usual. “Power outages are commonplace in Africa, but that kind of refrigerator will keep the food fresh without electricity for up to three days,” says Cavender.

Likewise, the overwhelming success of Chinese mobile phone brands in Africa is built on localization. Data from the India-based technology consultancy Counterpoint Research shows affordable mobile device brands Tecno and itel, both owned by Shenzhen-based Transsion Holdings, took the third and first spot respectively in the African mobile market in the third quarter of 2016. Taken together, Transsion has grabbed 40% of the African market, out-competing much bigger opponents like Samsung.

“Chinese smartphones and feature phones have bigger batteries because electric sockets for recharging may not be readily available to the African consumer,” says Shobhit Srivastava, Research Analyst at Counterpoint. “Similarly, these phones have two or three slots for SIM cards rather than one, as signal coverage remains patchy and a substantial number of Africans commute across borders.”

However, most phones are made in China and shipped over to Africa. Srivastava notes that while sales of mobile phones in Africa are likely to continue doing well due to the continent’s relatively low smartphone penetration rate of 50-60%, manufacturing such complex devices in Africa is likely some ways off.

“You would not readily set up a factory if you cannot even source basic things such as battery chargers locally,” Srivastava says.

History, Diplomacy, Economy

China’s involvement in Africa has received much recent coverage, but it is not entirely a new phenomenon. One of the earliest contacts was by famed admiral Zheng He, who made a once-off voyage to Africa in the 15th century. But direct involvement remained minimal before the modern era.

When Mao Zedong declared the People’s Republic of China in 1949, most of Africa was controlled by Western colonial countries, which had subjugated the continent in the 19th century. In the early years of the PRC, China used aid to spread the Communist message and to challenge the international influence of its rival, the Kuomintang-dominated government based in Taiwan, which still claimed dominion over the mainland.

“Their civil war became a diplomatic war, fought in the halls of ministries of foreign affairs across the third world,” writes Deborah Brautigam, author of The Dragon’s Gift, published in 2009. “Ideology and political strategy were then the primary thrusts behind China’s extensive aid program.”

China’s financial help has also clashed with Western efforts, not least because African leaders often preferred China’s “non-interference” policy. This generally means it does not link human rights or governance issues to aid and economic cooperation.

A key event in crafting non-interference while increasing investment was a 1995 Africa trip by Zhu Rongji, who became China’s Premier three years later. Zhu visited the Tanzania-Zambia (Tan-Zam) Railroad, the largest and most expensive foreign aid project China had undertaken up to that time.

The 1,162-mile long railway was constructed in the early 1970s to upstage the Soviet Union’s foreign aid efforts in the region. According to John F. Copper, an American political scientist and the author of China’s Foreign Aid and Investment Diplomacy, Tan-Zam was a resounding political success for China, but a practical nightmare, suffering from construction issues, frequent engine breakdowns and financial losses. But Zhu Rongji deftly turned the railway’s shortfalls into an opportunity for engagement.

“When Zhu visited in 1995, he cited the problems the Tan-Zam Railroad had encountered and promised to do something,” said Copper.

Then-President Jiang Zemin toured Africa the next year. He later spearheaded the Forum on China-Africa Cooperation (FOCAC), which paved the way for the rise in Chinese investment in Africa. FOCAC has been held five times since 2000, bringing together more than 80 ministers from China and 44 countries and representatives from more than a dozen international and regional organizations. China’s aid pledges made within the framework of FOCAC included building economic zones in Africa that attracted considerable funds and were effective in promoting economic growth.

According to Copper, the idea comes from the Chinese development playbook. Most prominent was the special economic zone (SEZs) initiated by the Deng Xiaoping reforms in the late 1970s, which attracted foreign capital and fostered economic growth. The SEZs have been a huge success, and building such zones abroad would expand China’s trade opportunities.

The first African SEZ was established in Zambia in 2007. There are now seven zones: in Algeria, Egypt, Ethiopia, Mauritius, Nigeria (two), and Zambia.

“The bulk of Chinese investment goes into zones and industrial parks, where there is cheap power because of [Chinese-built] hydro dams and low taxes,” said Charlotte King, Africa Lead Analyst of the Economist Intelligence Unit, a UK-based think tank. “These zones embody China’s approach: paving the way in Africa with help of government-government MOUs [Memorandums of Understanding] and letting the private sector doing the heavy lifting.”

Uncharted Territory

As China’s momentum in Africa has picked up, so too has the need to expand beyond economic involvement. A key event marking the deepening of China’s long-term commitment came in July, when China dispatched military personnel to set up its first-ever overseas base in Djibouti, the small, but strategically-placed country on the Gulf of Aden.

China’s agreement with Djibouti establishes a military presence in the country until at least 2026, with a contingent of up to 10,000 soldiers, according to international current affairs magazine The Diplomat. Its stated purpose is to resupply navy ships taking part in peacekeeping and humanitarian missions off the coasts of Yemen and Somalia.

Another apparent aim reflects increasing risks: to be ready to evacuate Chinese nationals from the region. China has already been forced to do this in recent years during the Yemen and South Sudan civil wars, as well as from Libya, when Western coalition forces toppled Muammar Gaddafi. But there are additional, even longer-term considerations in play.

“Although China will not say so, the Djibouti base extends its global power as its blue water navy needs support facilities there and in other parts of world,” says David Shinn, a professor who served as US Ambassador to Ethiopia and Burkina Faso. “Depending how China uses the Djibouti base, it may signal the end of the non-interference policy,” he adds.

One pressing question stemming from China’s engagement is if it is helping stabilize Africa, which, unfortunately, is accustomed to a certain amount of turmoil. Western voices often accuse China, with its policy of non-interference, of fueling corruption and civil wars in Africa. They also accuse Chinese FDI of exploiting Africa’s weak environmental regulations. African voices also often decry the loss of jobs resulting from Chinese imports flooding the market and the low wages Chinese firms active in Africa pay to local employees.

Shinn, in his opinion, says that the short answer is yes, China is helping to stabilize Africa. However, the full picture must include the risks associated with the large trade surpluses China has developed with African countries in recent years, except those exporting natural resources to China.

“If that trend continues it could be harmful to Africa,” Shinn says. “The other issue is that there are so many value-added goods coming in from Asia that it makes it difficult for African manufacturers to compete.” Neither the export nor import issues are close to being resolved.

Osita Agbu, Professor of International Relations at the Nigerian Institute of International Affairs, has a different take. According to him, the trade deficit is not dangerous as it reflects the importation not only of Chinese consumer goods but also machinery and equipment needed to make African economies reasonably competitive.

“The point is that while China does have a big role in Nigeria, we never had serious problems with them,” Agbu says. “The Chinese are setting up the Tinapa Free Trade Zone in Calabar [in southern Nigeria] and the Lekki Free Trade Zone in Lagos [Nigeria’s largest city with a population of some 16 million]. With their ports, warehouses and connecting infrastructure, these zones will ensure international transactions that will be good for the future of Nigeria, as well as that of the whole west coast of Africa.”

Positive, but Uncertain

The balance currently seems to be a win-win. A recent survey by pollster Afrobarometer showed 63% of 56,000 people polled in 36 African countries felt that China’s influence in their countries was somewhat to very positive. At the same time, the July McKinsey report showed that nearly a quarter of the Chinese firms in Africa said they had covered their initial investment within a year or less.

The main threat to China’s growing relationship with Africa is probably instability in African countries. For example, Kenyan President Kenyatta, who was embarrassed by the Chinese bridge collapse, won re-election in August in a contest that was then annulled by the Kenyan Supreme Court.

Tensions escalated with many fearing a repeat of the 2007 election standoff when a disputed presidential poll resulted in the deaths of more than 1,000 people and weeks of bloodletting. And it is important to keep in mind that Kenya is viewed as one of the more politically stable of Africa’s countries.

But Copper, the old African hand, downplays fears of such political mishaps derailing the long-term China-Africa cooperation. “This project is so big and has been so successful it can no doubt weather a few storms,” he says.