Long the purveyors of advanced skills and knowledge, Chinese sea turtles, or overseas returnees, are now finding a different environment back home.

Growing up in Mianyang, Stone Shi didn’t always fit into his surroundings. He particularly found it hard to fit in at school in the city, the second-largest in the southwest province of Sichuan. “It was a lot of struggle,” he says.

In junior high, while classmates buried their faces in textbooks, Shi began developing a “silly” interest in personal fitness. In breaks after the end of afternoon lessons at 4pm, he would cycle to the gym and work out before racing back to make the start of evening study. “I would eat my snack on the way, sometimes still eating when the class was starting,” recalls Shi.

His reluctance to focus on schoolwork did not endear him to educators. “Everybody was study, study, study. I wanted to exercise and it was a huge issue in the class.” The school called his parents in several times over the perceived problem, and eventually delivered an ultimatum—drop the fitness training.

He dropped China instead. In 2000, Shi left for the US at the age of 22. With a Master of Engineering degree from Texas A&M University and an MBA from Tuck School of Business at Dartmouth College in hand, he returned to China in 2010—turning down job offers from Google and a Silicon Valley start-up in the process—to launch his own business in Shanghai. The 37-year-old is what one calls a Chinese sea turtle or haigui (pronounced hi-gway), an overseas returnee who left home to study and work overseas before returning to a rising China.

Haigui are not a new phenomenon. Modern-day China is steeped in their legacy and the Communist Party arguably owes its existence to them. And in 1911 Sun Yat-sen returned from abroad to play an instrumental role in the establishment of the republic that ended thousands of years of dynastic rule.

More Chinese than ever are returning though, particularly since 2008 when Beijing hosted the Summer Olympics and the global financial crisis roiled Western markets. China’s economic growth is drawing some back, while others are being courted by local businesses seeking top-level talent.

The leadership also wants to entice more Chinese expatriates home. “You are warmly welcome if you return to China,” President Xi Jinping said in 2013. Previous appeals have worked in the past. “A lot of Chinese want to help the second generation or help the country to grow,” says Hubert Tam from Sirius Partners, an Asian financial executive search firm.

Returnees brought back advanced knowledge and skills in energy, agriculture and other critical industries. Others established new research fields, helping to restart the process of education, innovation and discovery that had been disrupted during the decade-long Cultural Revolution. Later on, others flooded into hi-tech fields, with e-commerce a prime example. Sea turtles have founded leading technology firms such as Robin Li’s Baidu and Tao Zhang’s Dianping (he also had a co-founder).

Overseas Chinese should heed Xi’s call with caution though. The sea turtles of today have it tougher than their predecessors. Competition for the best jobs is ferocious. Returnees compete not only with each other, but also against the thousands of other workers who stayed in China to sharpen their skills and experience. Once a rare and fettered breed, haigui are no longer unique and their ubiquity potentially undermines their once-prized status.

Across the Ocean

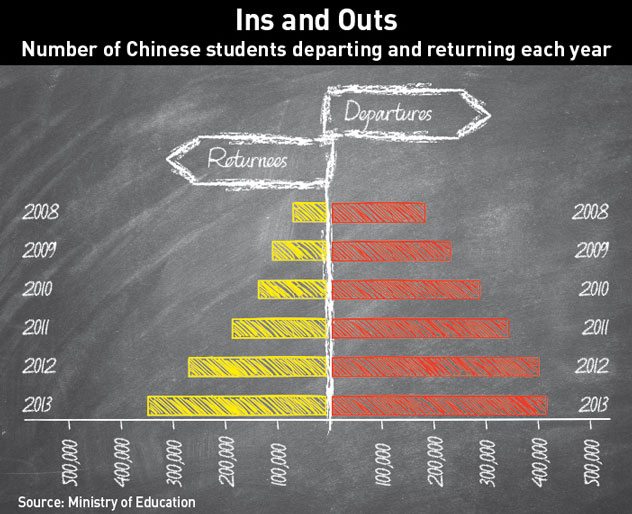

The vast majority of haigui originally left China for educational reasons. China has been sending students and scholars to study abroad for more than a century, with government-funded education overseas dating back to the late 1840s. In 1978—when China’s per capita GDP was less than $200, one-fiftieth of the US’s—the government expanded the number of students permitted to study abroad. From that year to the end of 2013, a total of 3.06 million Chinese had studied abroad, and in 2013 alone, 413,900 students travelled overseas for further education—making China the largest source of overseas students—according to the Ministry of Education.

They were funded by the government or employers, or at their own expense. Most of them landed in the US, Australia, Japan, the UK or Canada. That figure was up from 399,600 students in 2012 and 284,700 in 2010. Meanwhile, 353,500 graduates returned with a foreign degrees and experience in 2013, raising the total since 1978 to 1.44 million.

Beijing continues to play an important role in helping people acquire an education overseas. The state-sponsored China Scholarship Council—a non-profit that provides financial aid to Chinese citizens to study abroad—will send 25,000 students abroad in 2015, 17% more than the 20,400 in 2014. This year’s tally will include up to 8,000 more Chinese graduate and doctorate students. The council has sent a total of more than 160,000 Chinese students to study abroad since 1996, and 98% of them have returned home.

But far greater numbers pay out of their own pocket. Decades of economic growth in China have spawned an enormous middle class with the ability to fund expensive overseas tuition for their children.

That is partly reflected in data published by the Brookings Institution in August, which showed China’s wealthiest cities were the biggest source of Chinese students in the US, while Beijing and Shanghai were the second and third-biggest source of foreign students in the US between 2008 and 2012—with 49,946 and 29,145, respectively—after the 56,503 sent from Seoul, South Korea. And of the nearly 400,000 Chinese students who attended foreign higher education institutions in 2012, around 380,000—90%—were self-funded.

It wasn’t until the late 1990s that the number of returning Chinese students grew large enough to become a trend. That was arguably the golden period for haigui, as returnees typically had experience in economics, sciences or running large firms—skills China needed at that time. But greater affluence nowadays has allowed Chinese students to choose what they study, meaning that more haigui are returning with skills in less traditional fields, such as fashion and education.

“The number of haigui returning to China has been rising, just because there’s more people going out,” says Tam from Sirius Partners. “It’s a numbers game. People are getting richer and they have the luxury to go out for education.”

The reasons behind people choosing to leave have also evolved. The first people who went out and returned as China began its reform era were applauded because they left to acquire advanced skills or expertise that could aid the state.

But Chinese these days are more likely to be departing over frustration with the rigid methods and rote learning of the traditional educational system. Shi says grievances over the mindless memorization and competitive streak at school pushed him to look elsewhere. “It was quite disheartening and I really had huge trouble just fitting into the system… [which] I completely disagreed with,” says Shi.

That is why after graduating from Mianyang’s Southwest University of Science and Technology in 1999 with an engineering degree, Shi opted for graduate study in the US. Now more Chinese are following in his footsteps. Chinese students now make up 31% of all foreign students in the US.

Paddling Home

Family ties are a major reason for why haigui return to China. A survey conducted by British recruitment firm Hays last year shows the powerful personal pull of home. In a survey of 454 Chinese who are either studying or working overseas but considering a return to China, it found that 41% want to come back to live closer to family.

Impressive salaries and benefits attract some returnees who are in demand for their foreign experience and skillset, according to recruitment firms. A head-hunter lured Shi back to China with a job in product management at Cambridge Silicon Radio. Salaries in specific industries—such as finance and consulting—have grown rapidly to be competitive with the US and UK.

But higher taxes also mean a returnee can have more take-home pay than in the West. “The actual lump sum is bigger if they were working in the States, but what they actually take home at the end of the day after tax, expenses and everything is probably more in China,” says Tam. Moreover, Chinese authorities have begun enforcing a rule, normally ignored, that Chinese citizens must pay tax on their worldwide income, not just on their earnings in China.

But job satisfaction is also a key consideration, with 31% of the people polled by Hays saying they would be willing to take a drop in salary if it meant coming home to a good job. Meanwhile, a quarter of respondents revealed they were attracted by the possibility of an accelerated career path in China. That resonates with Shi, who describes a ‘bamboo ceiling’—like the so-called glass ceiling—for Asian males in the Western corporate world.

Another haigui working for a local company in Shanghai shared similar feelings, after growing frustrated at bumping up against career ceilings while employed at multinational firms. “I’ve worked in the US and Canada [and] it’s very difficult to head up a very senior role in a foreign country. There’s much more opportunity here—in Asia, in China—versus the US or the UK,” says the haigui, who would only speak on condition of anonymity.

In contrast, Chinese companies can often entice sea turtles home by offering them better positions with greater scope for decision-making. Coming home also means being closer to the action when it comes to top-level decisions at a local firm—a level of involvement that can go missing at foreign peers, who may map out strategy back in Western headquarters.

Chinese companies are also finally beginning to match the big ambitions of sea turtles. “Family ties are a strong motivator to bring talent back home, but also people who have lived and worked abroad are often highly ambitious,” says Sarah Jones, business director in north China for Hays. “If a couple of years ago, they looked to further their career, they went overseas. They’re probably still as ambitious as they once were back then, and now they’re motivated to achieve certain career goals by returning.”

The globalization and increasing sophistication of China Inc. has ratcheted up demand for haigui, who are highly sought after for their ability to understand Chinese cultural nuances while being trained in Western practices. Their cross-cultural ability and global mindset—understanding both East and West—dovetails with the demands of local large-sized enterprises expanding into new markets. Five or six years of foreign experience is very transferable to China, says Tam.

JD.com, an e-commerce company, launched a recruitment scheme in 2014 called the International Management Talent Program, designed to hoover up the best MBA graduates from top business schools around the world, many of whom in practice, due to cultural reasons, will be Chinese.

In its maiden year the program scoured six universities, including MIT, Yale and Oxford, and attracted 10 graduates—most of who had at least a few years of working experience at Western companies such as Amazon, PricewaterhouseCoopers and Verizon Communications. With CEOs and vice-presidents as mentors, the candidates are groomed to become the next generation of leaders in the company.

But foreign companies also compete aggressively for top talent. For them, haigui are appealing because of their overseas education and training, and familiarity with local customs. Foreign businesses want to tap into the China market and in order to do that, “you need to be mainland Chinese,” says Tam. Foreign financial firms, in particular, value haigui because they are bilingual and their experience abroad means they usually grasp the culture of the company more easily than a local.

In the Chinese financial industry, foreign companies trump local rivals when it comes to haigui intake. That is often down to the haigui themselves preferring multinational firms because “they know they have the edge”, says Tam. That leverage frequently sees returnees offered better compensation at non-local firms. “Haigui expect more. Their expectation will be much higher because they got an education overseas and they expect it to be repaid,” says a haigui at a large state lender in Shanghai.

Sunny Shores?

Some returnees dispute this, saying while some industries still aggressively recruit returnees, an overseas education no longer means a high starting salary or fast-track promotions. Moreover, employment at multinationals is not always rosy and can hinder a career in China in the long run.

“It’s not really as good as people think,” says the haigui with the state bank, citing the experiences of friends working at foreign institutions. They enjoy a salary premium over local hires at state-owned Chinese banks, but the basic wage makes up most of their compensation. “The base salary is better, but that’s not the total. You need to see the whole package,” says the haigui, who spoke on condition of anonymity.

Joining a foreign company also carries an element of risk. They remain subject to restrictions absent from their domestic counterparts, and not all of them survive China’s tough business environment. Under this backdrop, for haigui to hitch their career prospects to a multinational can be fraught with long-term risk. The danger is arguably even greater now that conditions have turned chilly for foreign companies.

Opting for a foreign company can create another problem in the long run. Many sea turtles who have worked at Western companies for years experience culture shock when they join a Chinese company. “There will be quite a bit of culture shock,” agrees Tam. “That’s going to be a difficult challenge for haigui.”

Turtles who have spent six or seven years working at a foreign business can find it “really hard” to switch to a state-owned company because their mindset is different, says the haigui from the bank. In multinationals, returnees frequently excel in the job by being quick, efficient and polished. But in state businesses, says the haigui, the job itself constitutes only a small part of one’s employment. “The job is really the basic thing. You need to think more about relationships with different levels in the company. It’s more about how to position yourself.” That kind of mentality can sometimes go missing in haigui, who began their careers in job markets that emphasise transparency, meritocracy and ethics.

Today’s turtles also face much tougher competition than the vanguard that went out 20 or 30 years ago. China’s economic ascendance has stoked pride among the population while helping the workforce shed some of its inferior complexity. Local professionals that stayed behind can come out on top, with local market knowledge and contacts highly prized by domestic and foreign businesses alike.

The hordes of Chinese going abroad have also diluted the overall quality of haigui. In the 1980s, Chinese studying overseas tended to be an elite group at the graduate level. Whereas Ivy League universities would have once been de rigueur, more and more Chinese are ending up at less prestigious institutions. Between 2008 and 2012, the most popular American universities for students from China were Michigan State University, Purdue University, Ohio State University, the University of Illinois and the University of Southern California, according the Brookings Institution, representing a wide range in quality and ranking. “Now there’re so many haigui. The quality is so uneven,” says a manager with a Chinese Internet firm in Beijing.

As more haigui come home, they render themselves more ubiquitous and less unique. Their stock soared when they were a rare breed, but now they are confronting a China that no longer values their skills and experience as much as before. Those who stayed have quickly skilled up and are squeezing out the need for haigui.

But as China retools itself into an innovation-led economy and goes out into the world, returnees are finding new ways to stay relevant—using their cross-cultural ability to help managers understand both foreign and local nuances. As long as China continues to seek improvement, there’ll always be a place for sea turtles carrying fresh ideas from foreign shores.