Chinese companies are increasingly abandoning Western stock exchanges and looking at relisting at home in China. What is driving them to do so?

Since early 2015, 47 Chinese companies have received combined offers of $43 billion in funding from private equity houses and Chinese internet giants to delist from American exchanges and make a run for the domestic stock markets. But so far only 14 of them have delisted and precisely none of them have managed to complete the journey and re-emerge on a Chinese exchange.

The sudden desire to rush for the exit represents a swift reversal of a quarter-of a-century flow of Chinese companies to the West. At its most broad, it is the result of two factors: the poor performance of many Chinese companies on US and other western exchanges, and the much higher valuations that companies can command on Chinese exchanges.

The prospect of riches in China is more attractive than the credibility of a US listing, but when the dream hits the reality of actually figuring out how to go private and then relist, things get messy.

“The bottom line is it’s hard,” says Michael Feldman, an independent analyst in Boston. “First they might need to do some corporate restructuring and then as we all know the [China] domestic IPO queue is years long.”

The China Securities Regulatory Commission (CSRC) was once keen to lure these companies home, but it has recently changed tack. It announced on May 6th that it was concerned about the huge valuation gap between domestic and overseas stocks.

Fraser Howie, an independent analyst and co-author of Red Capitalism: The Fragile Financial Foundation of Chinaʼs Extraordinary Rise, said that in his view, the regulator “doesn’t know what it wants and it’s trying to please a number of audiences at the same time.”

Shares in companies which have received go-private offers have fallen on concerns following the CSRC statement. Shares of the Nasdaq-listed Chinese dating app Momo Inc, for example, fell 8% after the CSRC’s comments.

The relisting frenzy began with a company called Focus Media, which sells advertisements on LCD displays. It delisted from Nasdaq in 2013, at which point it was valued at $2.6 billion. When it relisted on the Shenzhen Stock Exchange in December 2015 in a backdoor merger with an already-listed company, its market valuation more than doubled to $7.4 billion. In May 2016, its market cap was $22.3 billion.

These are very attractive numbers, especially for Chinese companies languishing in more rigorously regulated parts of the world like Wall Street. Deep issues of trust and problems of regulation and transparency have been wearing on the relationship for years, largely accounting for these companies’ lacklustre performance on US boards.

“Chinese companies don’t think they’re fairly treated. Financially and mentally these companies are suffering in the American market,” says Guo Chengang, a stock analyst in Shanghai who until recently worked in New York covering Chinese internet companies for Investment Technology Group. “There needs to be better understanding from investors.”

But the often opaque nature of Chinese companies is off-putting for many investors and the warm glow of business plans based on China’s huge population and endlessly hyper-fast growth do not resonate like they once did. Added to that are the suspicions generated by the many fraud cases involving Chinese companies that have been brought to light. One memorable example was Sino-Forest Corporation, a Canadian-listed tree supplier that was found to possess zero trees.

“No one should trust [these] companies,” says Howie. “There has to be a discount factor with Chinese companies.”

Money Talks

China’s stock markets last year were an extraordinary rollercoaster ride of boom and bust, but in early 2016, there was a spate of successful China IPOs. According to Bloomberg data, six companies on China’s stock exchanges took bids from IPO investors in orders worth RMB 7.1 trillion ($1.1 trillion) in January this year alone, but only because the regulator changed the rules and allowed bids with no money upfront, making it in effect a lottery with free tickets.

Currently, there are 147 Chinese companies listed on American exchanges with a combined market cap of almost $800 billion. Among the biggest are internet giants like Alibaba and Baidu and state-owned enterprises (SOEs) such as PetroChina and Sinopec. According to a McKinsey analysis in 2011, they came to America in three distinct waves.

The first wave in the 1990s consisted of major SOEs such as Shandong Huaneng Power and China Eastern Airlines. The second wave in the early 2000s included more massive SOEs like China Telecom and China Life and also some private companies. Together they totalled about 200 companies.

The third wave in the late 2000s was much larger, at around 500 firms. These companies were typically private and smaller, coming to US exchanges because they were unable to list on domestic markets due to the domination by SOEs.

Third-wave companies have had relatively short tenures on exchanges. Focus Media, whose Shenzhen relisting brought so much value, listed on Nasdaq in 2005. Qihoo 360, a Chinese information security provider, which inked a $9.3 billion privatization deal in March this year, listed on Nasdaq in March 2011. Bona Film Group listed on Nasdaq in 2010 and completed a roughly $1 billion buyout in April.

These companies are among many that have been tempted by higher valuations to go back home, although the trend has also included Hong Kong, which for decades has been a key destination for Chinese companies, even more so than New York. Alibaba, for instance, originally wanted a Hong Kong listing, but went to New York only after local authorities refused to change the rules to meet the companyʼs requirements. According to UBS research, over two-thirds of shares listed in both Hong Kong and China have a 50% higher valuation on the mainland.

“The story is a relatively simple one,” says Howie. “It’s all short-term moves to maximise profits at a particular point in time—at each stage it has made logical sense in terms of market dynamics.”

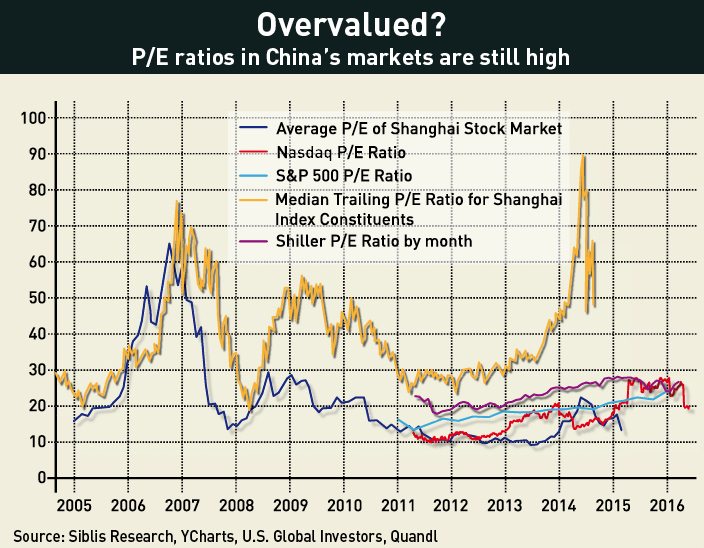

When Focus Media announced its Shenzhen backdoor listing plan last June, the average price-to-earnings (P/E) ratio on the ChiNext index, a technology-heavy exchange touted as China’s Nasdaq, was a 126-times multiple, eventually reaching 144 later in the year—Nasdaq’s P/E ratio was around 13 during the same period. Even after the Chinese stock market bubble burst in July, there was still more “bang for the buck” on Chinese exchanges compared with American ones, according to Guo. On May 8th this year, the ChiNext average P/E was still 70.

“Credibility Gap”

But as big as the pull toward domestic markets is, the push is just as strong, with many if not most Chinese companies facing the cold shoulder on Wall Street.

“American investors don’t believe the figures coming out of Chinese companies,” says Guo. He points to the fact that Facebook had an average P/E ratio of 76.58 during 2015 while Alibaba averaged 56.05 over the same period, despite Alibaba’s higher earnings performance.

Explaining the discrepancy, Howie sees reason to be doubtful. “Alibaba is dependent on a lot of independent merchants,” Howie says. These merchants are often accused of faking sales, meaning “there is genuine concern about the quality of the numbers.”

Compounding the issue is that many Chinese companies, Alibaba included, use a variable interest entity (VIE) structure to list in the US. VIE is a complicated mechanism that allows foreigners to invest in restricted industries in China by buying into an offshore company. Tencent and Baidu and many other foreign-listed companies have taken this route. But the gain in the ability to float stock overseas comes at the price of trust. “[Investors feel that] I, as a shareholder, have very little rights in this business,” says Howie.

An even bigger problem may be poor corporate governance and fraud—a problem common to reverse-merger companies. Research last year by Wang Zigan, Assistant Professor of Finance at The University of Hong Kong, found that of the 48 Chinese companies that were forced to delist by US regulators between 1998 and 2013, 85% were reverse merger cases. His research revealed a network of factors supporting malpractice in these firms.

“I find that the firms are assisted by professionals to help them circumvent the US regulations,” Wang wrote. “Further, I find that the social network of the linked directors facilitates the spread of their misconduct.”

Raman Chitkara, Partner and Global Leader in the Technology Practice of PricewaterhouseCoopers, also sees a direct link between backdoor listings, lack of information and stock price.

“Reverse-merger companies are ill-prepared to deal with being a public company. It’s not surprising that many of these companies have failed expectations,” says Chitkara. “If you have got that credibility gap, investors will get shy.” The problems go “hand in hand” with a lower stock price, he adds.

Although Focus Media made it back to China via reverse merger, its relisting looks less like a total success story when the full circumstances are considered. In 2011, the company came under pressure from short-sellers Muddy Waters Research, which claimed it was overstating the number of advertising displays it had in China. The company’s shares tumbled by 40% before it went private in 2013.

While the claims were not proven, Focus Media was ordered to pay $55 million by the US Securities and Exchange Commission for failing to disclose details of a sale of one of its subsidiaries to another part of the company. The price was six times lower than it was when sold a few months later to an external buyer. The case compounded doubts about the company’s credibility.

The problem extends beyond just the North American exchanges as well. The London Stock Exchange (LSE) has attracted 80 Chinese companies since 2005, including many on AIM, the small-cap market run by the LSE. But AIM has suspended many for insufficient due diligence. Similarly, since 2007 the German stock exchange Deutsche Boerse has attracted 23 Chinese companies, but a third have since delisted amid corporate governance concerns.

Many Chinese companies seem to list overseas without understanding the importance of transparency. Analyst Michael Feldman, who has helped many Chinese companies list in the US, believes there is a basic difference in management culture.

“A lot of smaller ones feel ‘why do investors need to know this [information]? It’s not important,’” Feldman says.

Charmed by the Government

Alongside the difficulties that are encouraging Chinese companies to leave foreign shores, the Chinese government and securities regulators have, until recently, been making various moves to draw companies back home.

In December last year, the State Council announced its intention to allow the Shanghai Stock Exchange to create a strategic emerging industries listings board to promote the relisting of companies in sectors such as internet services, biotechnology, IT and new energy. Crucially, the new board would lower the profitability requirements of companies wanting to list. (US exchanges lack a profitability requirement.) Howie, however, sees this proposed board as “having little influence” pointing out that China already has the ChiNext, its equivalent of the Nasdaq.

The government last year also announced the removal of the 50% cap on foreign investment in e-commerce companies operating in China, and encouraged financial institutions to get behind technology companies. Investment bank China Renaissance has partnered with Citic Securities to raise funds to assist companies looking to return home and Shengjing Management Consulting has also launched a fund of funds to bring Chinese companies home.

All it’s Cracked Up to Be?

Would-be returning companies that manage to get all their ducks in a row still have to make it through the Chinese listing process, which is by no means straightforward.

“It sounds like a good idea if you could do it all in one day,” says Howie. There were 675 applications pending at the end of 2015, most of which will have to wait at least two years to list. And all IPOs were stopped in the immediate aftermath of last year’s Shanghai stock meltdown, which could conceivably have an encore.

To solve this problem, the government announced last December that it intended to introduce a US-style market where companies could list if they meet certain financial conditions, removing politics and speeding up the process.

“You have this problem that you need government approval, however good a company you are. You’ve got to remove this moral hazard,” says Howie. But he believes the change won’t happen anytime soon. “[That] reform has been talked about for over a decade.”

Liu Shiyu, head of the CSRC, said in March that the reform would take time. Meanwhile, many US-listed China companies are getting anxious.

“Everyone thought China was going to welcome these companies with open arms, but there are a lot of structural issues these companies have to work out,” says Feldman.

Crucially, alongside all the structural issues with China’s stock markets, is the CSRC’s apparent change of heart.

According to Howie, whilst once the regulator was “encouraging these companies coming home to help capital markets,” now “the regulatory environment in China has got substantially worse, to the extent that the regulator may ban [these] reverse takeovers. They’re concerned about domestic investors in China due to companies that are not doing that well in the US being dumped on Asian markets. This is a regulator that’s paranoid about small investors being on the street. It’s trying to regulate the market and trying to ensure people don’t lose money.”

The fear is that local investors will be in line for losing money if these companies return home on sky-high valuations which then subsequently fall when the market corrects.

The mooted strategic emerging industries board also now seems to be on the backburner, with mention of the new board not included in the government’s 13th Five Year Plan, released in March.

More broadly, Chitkara believes some of the companies may be reconsidering their decision to delist. “The initial reasons for listing in the US—publicity, marketing value, liquid markets and better valuations if you can deliver on growth promises and flexibility in corporate governance structure such as multi-voting stocks—are still valid.”

One possible bellwether was a decision by an investor group including the founder of smartphone maker Xiaomi, Lei Jun, in May to pull out of a $2.5 billion deal to take private the Nasdaq-listed Chinese karaoke company YY.

Just how many Chinese companies return home from US exchanges is unknown at this point.

“They may find China is not the rosy market they expected,” says Feldman.