A less-than-healthy regulatory environment is holding back the Chinese pharmaceutical industry

A police investigation into a vaccine trading scheme in the eastern Chinese city of Jinan was nearly a year old when the story broke in March 2016. The news quickly went viral as outraged parents, citizens, and lawyers questioned how over two million expired vaccine shots could have been approved for distribution to hospitals and clinics throughout the country.

The scandal was just the latest setback for China’s pharmaceutical market, which is being held back by a dysfunctional healthcare system. On the consumer side, hospitals are overly reliant on drug sales for revenue, and doctors are chronically underpaid, both of which have led bribery scandals and even attacks on doctors by disgruntled patients, and of course drug safety. On the drug development side, pharmaceutical companies domestic and international are hamstrung by onerous regulations. And on top of that, the regulatory apparatus itself is under threat from corporate poachers armed with high-paying job offers.

The combined weight of these and other unresolved issues dragged pharmaceutical sales growth in China by multinational pharma companies down from over 20% in 2013 to only 5% in 2015. But even this hasn’t stopped global drugmakers from placing big bets on continued China market growth.

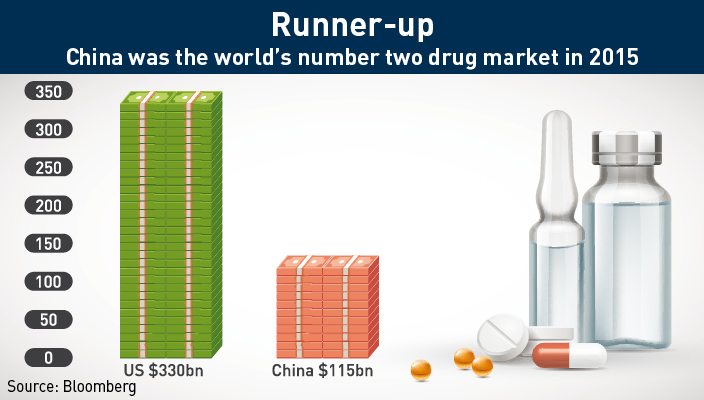

Last year, overall pharmaceutical sales in mainland China totaled over $115 billion, placing China behind only the United States ($330 billion). With a population of over 1.3 billion, the sheer size of the market all but guarantees that the Chinese market will continue to grow in spite of any problems faced by the healthcare system.

“Healthcare is the one market where the market size equals the population,” says Kent Kedl, a Senior Partner in Shanghai at Control Risks, a London-based global risk consultancy. Kedl has directed crisis management for several high-profile cases in China’s healthcare sector. “Not everyone will buy premium oncology drugs or AIDS treatments, but everyone needs healthcare at some point.”

Sickness Market

China’s large and still growing population makes it an ideal market for local companies as well as multinationals. But it is money—rising household wealth and rapid increases in healthcare spending—that has transformed China into the world’s second-largest pharmaceutical market. According to the World Bank, annual per capita expenditure in China on healthcare rose from $44 per person in 2000 to $420 in 2014 and this trend is set to continue as wages and living conditions improve.

Further driving demand are Chinese citizens’ changing lifestyles and habits. Living in crowded, polluted cities and working at white-collar desk jobs has dramatically increased the incidence of chronic ailments such as hypertension, diabetes, arthritis, cancer and cardiac disease. These health issues, once considered more Western problems, have sparked demand for new, advanced drugs to lower blood pressure, ease aches and pains, and lengthen life spans.

China’s aging society is also driving demand. Currently, around 16% of China’s population is over the age of 60, but this percentage is expected to grow considerably in coming years, with some estimating that nearly 25% of China’s population will be over 60 by 2030. Although this demographic conundrum vexes Chinese authorities, the growing elderly population will very likely be a boon for the healthcare industry.

With such fantastic growth potential, the number of local drug companies has risen to keep pace with China’s swelling demand. Many of these domestic drugmakers first appeared during China’s ‘opening up’ period in the 1980s, as the government started to promote new drug development and provide assistance to local manufacturers. According to the Council on Foreign Relations, a New York-based think tank, the number of domestic drugmakers in China increased from around 680 to over 6,000 between 1980 and 2000.

Recognizing the pharmaceutical industry’s enormous potential, Beijing included additional policy support in the 12th Five-Year Plan unveiled in 2011. The plan highlighted life sciences as one of the “seven emerging strategic industries” that would fuel China’s future growth. Accordingly, the government has incentivized local drug development by investing over $1 billion in drug R&D, aimed at disease research, facilitating start-ups, and incentivizing the establishment of new R&D centers.

Multinational companies have also taken advantage of the generous incentives by establishing on-the-ground R&D centers.

“China encourages companies to locally manufacture their R&D products,” says Katherine Wang, a life sciences regulatory lawyer and partner at Ropes & Gray LLP. “In principle, companies with local operations are eligible for fast-track approval for new products.”

These benefits have encouraged multinationals to establish research campuses in Shanghai, a city quickly becoming a global pharma R&D hub. In 2014, Sanofi established its Asia-pacific Research center in Shanghai, while earlier this year, Novartis finished work on a $1 billion research campus located on the outskirts of the city.

At the same time, highly-skilled researchers born in China and now working abroad are being wooed back home.

“Qualified research scientists are being offered generous compensation packages to return to China and work for Chinese companies,” says Kedl. These returnees have expanded the local talent pool, allowing companies to pursue more advanced research projects.

Together, the combined effects of favorable policies and repatriation of skilled scientists are transforming China into a key link in the global pharmaceutical manufacturing chain. In 2012, China became the world’s largest exporter of active pharmaceutical ingredients (APIs). APIs are the biologically active parts of a medicine and include pharmaceutical mainstays such as penicillin, ibuprofen, morphine, and vitamins. In 2013, Chinese companies produced over 2.7 million tons of APIs.

China has also become an ideal location for contract research organizations (CROs)—companies that provide support to pharmaceutical, biotechnology, and medical device industries worldwide. Epitomizing the rapid expansion of China’s drug R&D industry, Shanghai-based WuXi AppTec has grown into one of the world’s largest CROs. Capitalizing on high demand growth, it has expanded its capabilities to provide a panoply of services.

“Other than a CRO, WuXi has successfully built an open-access platform with end-to-end drug discovery, development and manufacturing capabilities that can substantially lower the cost and increase the speed of testing a scientific hypothesis, thereby improving R&D productivity,” says Dr. Steve Yang, WuXi’s Executive Vice President and Chief Operating Officer.

But while WuXi regularly collaborates with biotech companies around the world, Chinese drugmakers have found it more difficult to translate domestic preeminence into international success. This is partly due to China’s expensive and time-consuming drug approval process.

“When you apply for a new product approval in China, this requires a local clinical trial on Chinese patients. This requires another approval,” says Wang. “Companies basically have to go through two approval processes: one for the clinical trial and one for the actual product approval.”

Waiting for approval to begin clinical trials can take upwards of a year in China, double what it takes in the US and Europe. And then approval of the final product dossier can take months to years. While multinationals, too, must slog through this lengthy process, they have the advantage of being able to sell in Western markets to generate revenue while awaiting approval in China.

But the bigger issue is China’s healthcare system—an outdated setup facing the dual pressures of rising healthcare costs and a steadily growing pool of healthcare recipients. To truly free up China’s domestic industry, Beijing will have to make tough decisions regarding doctor compensation and hospital revenues.

Rescuing Healthcare

While scientists researching the new medicines are receiving better and better pay packages, the doctors actually prescribing medications are chronically underpaid and overworked. Because of this, many doctors have come to rely on under-the-table handouts and gifts to supplement their meager salaries.

Chinese doctors’ need for higher salaries combined with multinationals’ desire to push their products onto the market has encouraged bribery. Patients, frustrated with lengthy wait times and suspicious of doctor’s true motives, have even physically struck out at hospital staff. In 2014, there were over 1,400 such reported “security incidents” in hospitals—stories of patients attacking doctors have become familiar media headlines.

Hospitals themselves have also become reliant on drug sales to generate anywhere between 40% and 60% of their total revenue, and according to Bain & Co., almost all of their profits. In contrast, in the US, pharmaceutical sales only account for around 10% of overall healthcare spending and a much smaller chunk of hospital revenue. This dependence has created a system whereby Chinese hospitals sell products at higher prices to patients, who in turn pass the cost on to health insurance. This has created a headache for regulators who want to expand access to healthcare and promote local industry while simultaneously reducing costs.

“Regulators can talk about changing prices, but right now hospitals rely on mark-ups to make money,” says Kedl. “You can take this away from them, but they still need to make money.”

Additionally, health scares and corruption scandals continue to rattle citizens’ confidence in locally-made products. Incidents such as the 2002 SARS outbreak, the 2007 toxic cough syrup case, and the 2008 poisoned baby formula scandal linger in the public consciousness. This year’s vaccine scandal has reignited concerns.

“The vaccine scandal further shattered my faith in China’s medical system,” says Pengqiao Lu, a China market analyst who recently moved to United States. “[It] has made me reluctant to visit the hospital in China.”

Huang Jing, a new mother with an 11-month old son, shares similar feelings of distrust.

“I’ve been closely monitoring the Chinese vaccine scandal, but there’s not much I can do besides postpone my son’s vaccination date,” she says.

Chinese authorities, well aware of the public’s flagging trust, have begun to clampdown on the flow of money circulating among drugmakers and doctors.

In a landmark 2014 case, a Chinese court found GlaxoSmithKline, a UK multinational drugmaker, guilty of bribery. Along with a $488 million fine, the fallout from the case damaged GSK’s reputation and forced the company to overhaul its China marketing. The case reverberated throughout the drug industry.

“It was a wake-up call,” says Kedl. “Up until the GSK case, multinationals mainly had to deal with the US Foreign Corrupt Practices Act, and, to a lesser extent, the UK Serious Fraud Office. Now these companies also have to pay attention to the CFDA [China Food and Drug Administration] and local Chinese corruption laws.”

The threat of being taken to court has complicated life for multinationals because most lack experience working with local regulators to ensure compliance with newly enforced bribery laws.

“The new laws are challenging companies’ government relations departments. Prior to the GSK case, they mainly worked with getting new products approved. Now, government affairs has become a whole different animal,” says Kedl.

Adding to the challenge is the lack of qualified staff at the CFDA. Just as Chinese scientists have been lured away from pharmaceutical positions in the US or Europe, regulators at the CFDA have been enticed by local drug companies promising lucrative pay packages. This brain drain has made it difficult for understaffed regulators to keep an eye on new developments.

Responding to questions regarding the recent vaccine scandal at a March 2016 news conference, CFDA head of drug supervision Li Guoqing candidly admitted, “There are dead spaces and blind zones for regulation and inspection.”

These “dead spaces” have made it difficult for both regulators and drug companies, not to mention increasing public risk.

Road to Reform

Faced with a daunting set of challenges, Chinese authorities have moved to separately address each of the problems facing China’s healthcare and pharmaceutical industries.

To create a stable, functioning healthcare market, regulators must tackle three main issues, according to Kedl. First, regulators must reform how hospitals are compensated. Currently, state and local governments only provide around 10% of total funding to public hospitals. Second, doctors must receive greater compensation. Finally, state and local governments need to agree on one procurement process for drugs. Currently, it is not clear who has the final say in negotiating the prices that hospitals pay for drugs. This system makes it difficult for drugmakers as well as hospitals.

To improve China’s drug approval process, the CFDA’s first step has been to aggressively recruit more trained staff into its ranks, according to Andrew Yu, Director of Strategy and Operations at Deloitte China.

“The second step has been to establish a ‘green channel’ mechanism that expedites the approval process for innovative drugs in high demand,” he says.

In 2013, this “green channel” allowed US drugmaker Pfizer to bring an innovative lung cancer drug to China’s market in only 11 months—a previously unthinkable timeframe for a brand new product. “Finally, in July 2015, the CFDA raised the requirements for generic drugs and forced companies to provide evidence that their products are as effective as existing innovative drugs,” Yu says.

Drugs that failed to meet these standards would be dropped from the approval process, thereby reducing the backlog current clogging the CFDA approval pipeline.

An additional concern for drug companies is China’s spotty intellectual property record. Nevertheless, “China’s IP laws have made big strides in recent years. Multinationals are more likely to stay away due to the lengthy registration process rather than fears of copying,” says Yu.

Foreign brand name products also carry an additional advantage.

“While there is always the risk of a copycat product being released, there is a general belief among the Chinese population that brand-name, international products are superior to local drugs,” Yu says.

Prognosis

Reviving China’s healthcare system and reforming the country’s drug approval process will take considerable time, and it is impossible to forecast how these separate but complementary changes will play out. But despite the uncertainties, all of the elements are there for China to become a global pharmaceutical hub, with rising domestic demand, qualified professionals, top-level political support, and foreign interest in the local market.

China may still have a way to go before it can launch its own, homegrown blockbuster drugs, but the market will probably be there to support them when they appear.

“Despite all the challenges in the healthcare sector, this is the one sector that everyone is betting on,” says Kedl.