China has rapidly established itself as one of the biggest players in the global green finance movement. But how green are China’s green bonds in reality?

China has rapidly established itself as one of the biggest players in the global green finance movement. But how green are China’s green bonds in reality?

It’s not often that financial reforms are compared to wonders of the ancient world, but December 19, 2017, was no normal occasion. On that day, China launched its first national carbon trading scheme, covering a massive 3 billion tons of carbon emissions.

Overnight, Beijing became the operator of by far the world’s largest carbon exchange, surpassing even the European Union’s Emissions Trading Scheme. When asked to put the initiative into context, Nathaniel Keohane, Vice President of the Environmental Defense Fund, a New York-based charity that assisted the Chinese government on the project, reached back into history.

“This is an incredibly ambitious exercise,” Keohane told the South China Morning Post. “It’s like the Pyramids of Giza.”

Such hyperbole is common in discussions of China’s rapid rise within the world of green finance, a new approach to funding that aims at ensuring that capital is channeled into sustainable projects. As late as 2015, China barely registered as a player. But in November that year, President Xi Jinping’s government made developing the field a priority in its latest five-year plan and the effect was almost instantaneous.

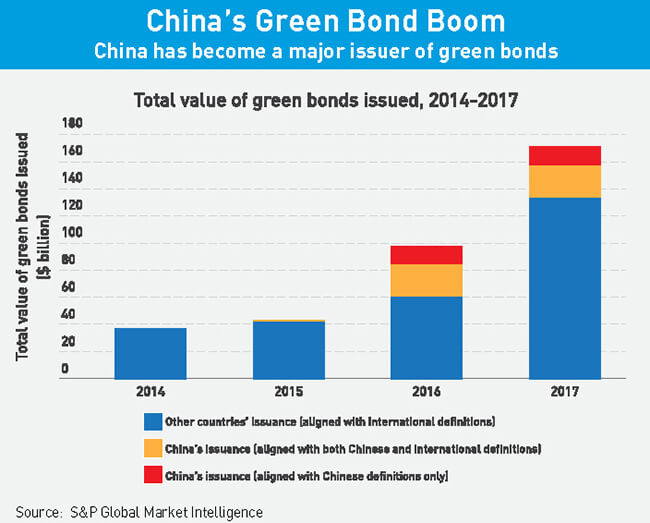

In 2016, China became the world’s largest issuer of green bonds, raising $33 billion from 43 deals, compared to just $1.3 billion the previous year. That September, China also became the first country to make green finance a major part of a G-20 summit when it hosted the event in Hangzhou.

By November 2017, the United Nations Environment Programme (UNEP) was impressed enough by the country’s rapid progress to declare: “China has firmly established itself as a global leader on green finance.”

The Chinese leadership has been quick to embrace the role of green pioneers. Some are even talking about China exporting its sustainable practices through its $1 trillion infrastructure-building program, the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI). Yet China’s green finance credentials remain controversial. Many analysts argue that if you scratch under the Chinese system’s green veneer, it reveals a different color entirely.

Funding Gap

China has stronger motivations than most countries to push its financial system in a more sustainable direction. A desire to meet its climate change obligations is part of it: Xi famously promised President Barack Obama in 2015 that his country would launch a cap-and-trade scheme by the end of 2017 and kept his word, with 12 days to spare. But green finance for China is primarily about pollution.

Simon Zadek, Co-director of the UNEP Inquiry into the Design of a Sustainable Financial System, believes the start of China’s green finance push traces back to January 8, 2013. That was the day the “Airpocalypse” hit Beijing and the city’s air quality index (AQI) soared to 960, over 20 times higher than the level considered safe by the Chinese government.

“After that, everybody only wanted to talk about one thing—pollution and the environment,” Zadek tells CKGSB Knowledge. “For the first time, in my view, ‘green’ became a political issue in China.”

This view is echoed by Ma Jun, the former Chief Economist at the People’s Bank of China (PBOC). “China has now… the most complete set of data on the PM2.5 AQI in the world,” Ma told Eco-business.com during a recent interview. “This transparency has enabled people to pay greater attention to… anything contributing to the improvement of the environment, including green finance.”

Xi Jinping has placed dealing with environmental issues at the center of his policy agenda. He has called on the government to shift the economy from high-speed to high-quality growth, and even placed environmental issues alongside gross domestic product (GDP) growth as the top issue on which officials’ performance is assessed.

“There are a couple of key mandates for Xi Jinping: there’s the Belt and Road Initiative and there’s the environment,” says Andrew Collier, Managing Director of Orient Capital Research, a Hong Kong research firm.

The problem is that cleaning up China’s poisoned air, water and soil and transforming its industry-dependent economy is a vast task, one that dwarfs even the Chinese government’s enormous budget. The PBOC has estimated that greening China’s economy will require investment of RMB 3-4 trillion ($470-620 billion) per year, and that the government will only be able to directly fund 10-15% of that amount.

To achieve its ambitions, the government needs to attract investment from the financial sector, private companies, households and international investors. Green finance offers the opportunity to do that.

Green Shoots

China has made impressive strides toward creating the architecture for a green finance market. In August 2016, the government issued the Guidelines on Establishing the Green Financial System. Ma from the PBOC hails this as “the world’s first attempt at an integrated policy package to promote an ambitious shift toward a green economy.”

The policies have produced concrete results. China raised $37.1 billion from green bonds last year, accounting for 15% of the global total. The amount of debt owned by the main Chinese banks classified as green credit has risen from $810 billion in 2013 to $1.2 trillion as of June 2017, says Gracie Sun, an adviser from the Green Finance Center at the Paulson Institute in Shanghai.

The number of green funds registered with the Asset Management Association of China, meanwhile, nearly doubled from 144 to 265 in 2016. And a massive 7,826 public-private partnership deals for green and low-carbon projects worth $1 trillion were registered with China’s national PPP project catalog, according to the UNEP’s Establishing China’s Green Financial System 2017 report.

This rapid progress has been possible because of China’s state-driven system. “It’s basically a Xi Jinping top-down policy, and whenever that happens everyone has to pay attention,” says Collier, of Orient Capital Research. “You have the China Development Bank behind a lot of this, and the minute you have significant policy banks pushing a theme then the cost of capital is lower.”

In fact, Zadek from the UNEP believes that in some ways the Chinese system is uniquely suited to promoting green finance because the state has the muscle to align the financial market and the country’s economic objectives.

“China’s PBOC would be seen by organizations such as the OECD as beyond the pale because it is combining policy and regulatory agendas,” says Zadek. “But that’s what allows them to look more systemically at the nexus between financial markets, environment and national development priorities.”

But this strength also has a downside, which is that state or state-backed investors still dominate the nascent green finance market. The China Development Bank (CDB), for example, issued 21% of the green credit in the Chinese market as of 2015, according to research organization New Climate Economy.

Many of the PPP deals, meanwhile, are not public-private partnerships at all. They are public-public tie-ins between local governments that are often heavily indebted and state-owned enterprises (SOEs), which sometimes have even greater debt levels and are being propped up by local governments and lenders.

This kind of partnership is banned, but still widespread. In April, a government crackdown led to more than 2,000 PPP deals being canceled, though how many projects were related to sustainability is not clear.

This suggests that the green finance system is not yet ready to become a long-term mechanism for lifting the burden on the state by attracting funding from a wide range of private sources. Though there are tentative signs of progress.

While only $6.6 billion of the $37.1 billion raised through green bonds last year came from overseas, new initiatives such as allowing Chinese banks to issue green bonds via the Bond Connect Scheme, which enables international investors to access China’s bond market through a Hong Kong trustee, have been effective. The first such bond, worth $450 million, was issued by the Agricultural Bank of China last year and was oversubscribed 4.4 times.

Color Blind

To entice more international investment, China may need to deal with a serious PR problem. For every article praising China as a trailblazer, there is another putting its high numbers down to “greenwashing,” the practice of disguising environmentally harmful projects as green investments.

Sam Geall, an associate at the UK think tank Chatham House, believes that the green credentials of some of China’s projects are murky at best. “There is still a long way to go in terms of clarifying what’s green about a green bond,” he says. “If these bonds can be used to finance new coal-powered generation then I think that’s a genuine cause for worry.”

The case Geall is referring to is Tianjin SDIC Jinneng, a power company, issuing green bonds worth $150 million in 2017 to finance a 2,000-megawatt coal-fired power plant. In the West this kind of investment is seen as incompatible with green finance. Yet Chinese experts point out that upgrading outdated coal plants with cleaner alternatives is crucial to dealing with the country’s air pollution problem. More than 60% of China’s power generation still comes from coal, though this is declining.

According to Ma, the debate over greenwashing reflects the difference in priorities between the West, where green finance is mainly about tackling climate change, and China, where pollution is the number one issue.

“Defining green finance isn’t just a matter of basic technology, it also reflects a nation’s environmental protection priorities,” he told Caixin. “Clean coal reflects this: China needs to prioritize reduction of air pollution, so it’s going to put a lot of effort into reducing emissions of sulphur dioxide and nitrogen oxides… by the use of scrubbing technologies.”

Another issue is lack of transparency in China’s financial system, which makes it difficult to be sure that funds labeled green are actually being used for sustainable projects. Only around $1.5 billion worth of green bonds issued by China in 2017 were deemed not to meet international standards due to a lack of disclosure, according to the China Green Bond Market 2017 report, but this figure may not capture the extent of the problem.

“The data are weak,” affirms Zadek. “But we’re fairly early on in the change process, and so one is cautious in drawing definitive conclusions.”

Sun from the Paulson Institute insists matters are becoming more transparent. “People learn lessons from the previous stage and what to focus on next,” she says. “Things are moving quite fast.”

Zadek agrees that the green finance push is helping to drive an improvement in the culture of China’s finance industry. “We know that there is a more studious and senior level-driven approach to assessing environmental risks on the bank balance sheets,” he says. “We are seeing improved due diligence, improved metrics, improved verification and improved public reporting.”

Yet China’s focus on pollution over climate change makes attracting investment more challenging in another way: Chinese issuers are funding different projects to peers in the West, and these projects offer more uncertain returns.

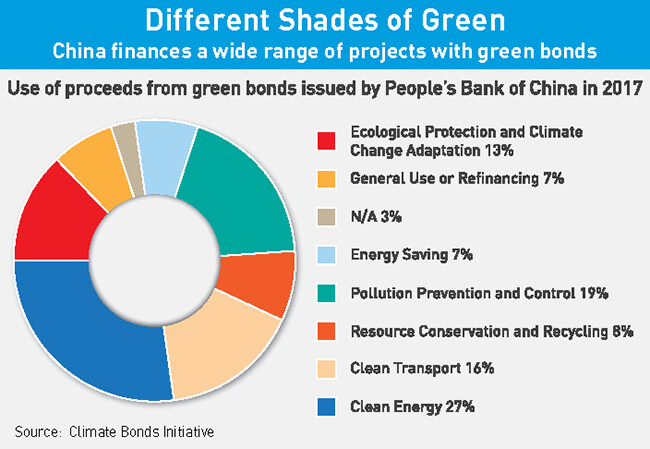

By far the most popular green bonds on the global market are for clean energy and energy efficiency projects. These made up 33% and 29% of the market in 2017, according to the Climate Bonds Initiative. China’s market is more diverse. Clean energy projects make up 27% of the market, but the next most popular are pollution control (19%), clean transport (16%) and ecological protection (13%).

Charles Donovan, Director of the Centre for Climate Finance and Investment at London’s Imperial College Business School, is doubtful about the profitability of many of the projects. “I see a lot of situations in which finance is seen as a way of covering over the fact that the policy or the regulatory structure doesn’t really enable a profitable investment,” he says.

Ma, on the other hand, argues that the projects will pay off in the long term, but that bonds need to have a much longer maturity. “A lot of green finance projects—subways, railways, water treatment, solid waste, new energy—have lengthy investment periods,” he told Caixin. “It might be 10, 15 or even 20 years before investments see a return.”

Stepping up the Pace

All these discussions ignore the obvious. Despite China’s headline-grabbing progress on green finance, the financial products are just a means to an end. The real objectives are blue skies and lower carbon emissions. On those fronts, China still has a long way to go, says Zadek. “The direction is right, but the pace of travel is inadequate,” he says.

The underlying issue is that China’s high pollution and carbon emissions levels stem from the way its economy is structured, according to Collier from Orient Capital Research. “China’s GDP is heavily industrial-oriented and much of that is heavily polluting,” he explains.

Unless Beijing takes more radical action, green finance will be nothing more than a band-aid. Although China was the world’s second-largest issuer of green bonds in 2017, green bonds still only accounted for around 2% of the total bonds issued in the country, according to Sun.

The same contradiction is seen in China’s Belt and Road Initiative. Though Sun argues that there is a genuine desire on the part of the Chinese government to adopt global standards on green finance and help BRI partners meet those standards, Geall from Chatham House points out that, “there are plans to build coal-fired plants in Turkey, Pakistan, Sri Lanka, Vietnam, Indonesia, Malaysia, the Balkans and so on.”

The reason for this contradiction, Geall suggests, is Beijing’s reluctance to move against its giant state-owned industrial firms, which employ millions and wield significant power. “My hunch is that there is a protracted bargaining process between [the Chinese government] and vested interests and strong incumbents who are seeing their markets shrink in China and are looking for an overseas outlet,” says Geall.

The trade-off for regulating the domestic coal industry may be allowing the SOEs to build dozens of new plants overseas. The punchline, as Zadek points out, is that if China wants its green finance push to make a real contribution, more—not less—state meddling is required.

“If you want to deal with carbon lock-in on the Belt and Road, that takes central government policy intervention,” says Zadek. “There’s no other way to do it.”