Less money is flowing to private enterprise in China.

Zhang Qingli has little interest in investing further in his textile business, as rising labor costs and raw material prices, as well as falling sales prices continue to shrink his profit margin.

“I don’t dare to invest more, not until a trustworthy client can promise me stable flows of orders,” says Zhang, whose factory in China’s eastern Jiangsu Province mainly exports products overseas.

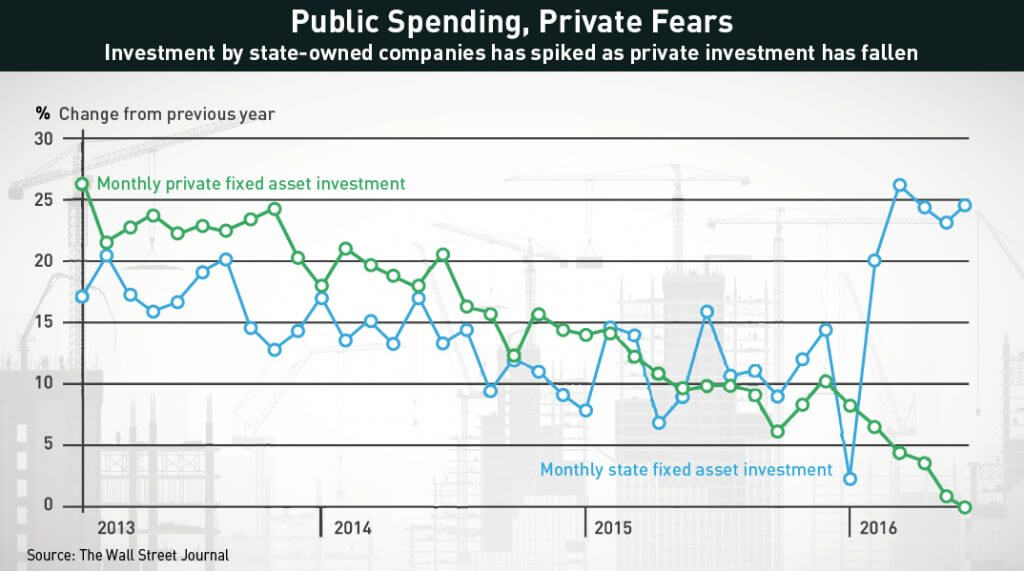

Zhang is not alone in his limited confidence in the future. Private investment in China, in terms of capital goods like factories and trucks, grew by just 2.1% in the first eight months of 2016, after a nearly 30% average annual growth rate over the past decade. In June 2016, it fell to a record low since China started tracking the data, and dipped even lower in July and August.

The pullback is happening just as the domestic economy is shifting to lower gear. The economy expanded 6.9% in 2015, the slowest pace in a quarter of a century, and is expected to cool to 6.6% in 2016, and slow further still to 6.5% in 2017, as the government continues policy support to help ward off a sharper slowdown.

While China’s state-owned enterprises dominate the monopoly industries such as petroleum and telecoms, the country’s private economy is still the major source for growth in production, employment and exports. Indeed, it was the private sector that created the Chinese economic ‘miracle’ of the reform era.

“We have to realize that private investment is rather large and works as a strong driver for consumption and job creation,” said Premier Li Keqiang at a conference in July with local government officials. He added that private investment is not only a concern for now, as it will affect economic development for years to come.

But whether the Chinese government has the ability to stimulate private business is unclear.

Who Hit the Brakes?

China’s overall investment growth—including state investment—has slowed down only slightly, from 10.1% at the end of last year to 8.2% in September. But private sector investment in the same period slid from 10% to 2.1% in August, before inching back up to 2.5% in September.

“There is simply no profit to hunt for,” said Liu Dongliang, senior analyst with China Merchants Bank. “The return on investment has dropped, so why bother to invest further.”

Private companies are more sensitive to economic changes, and will jump out of a sector if profit margins shrink. State-owned firms, however, have more complicated goals, including supporting government policies, and are more likely to soldier on.

With investment opportunities sparse, Chinese firms reported an 18% jump in cash holdings during the latest quarter, the biggest increase in six years. The $1.2 trillion stockpile—which excludes banks and brokerages—grew at a faster pace than in the US, Europe and Japan, according to data compiled by Bloomberg.

Not all sectors are suffering from the investment slowdown. In the first eight months, infrastructure investment—almost entirely state-funded—increased by 19.7%, “playing a key supporting role in stabilizing investment growth in the country,” says Wang Baobin, a senior statistician from National Bureau of Statistics.

But China’s strategy to prop up economic growth by pushing large-scale projects could also potentially sideline the private companies that account for three-fifths of China’s economy and four-fifths of its labor force. The government’s push for infrastructure projects usually come with financial and policy support, funds that are therefore not available to bolster private companies.

A survey of China’s industrial economy by the Cheung Kong Graduate School of Business pointed to the same trend. Only 9% of firms polled made fixed investment in the second quarter and a mere 2% made expansionary investment. The sluggish pace of investment looks like it will not improve in the third quarter as only six firms of about 2,000 said they planned to make investments.

“Recent media reports have noted that the country’s fixed investment during the first six months of this year was dominated by government-led investment, while private investment has been contracting. Our survey has found this trend to be a persistent one,” said the survey report.

There are, however, voices saying that the China’s private investment spending isn’t completely falling off a cliff. Analysis by Nicholas Lardy and Zixuan Huang of the Peterson Institute suggests the official data has exaggerated the decline as the government’s RMB 1 trillion bail out of the stock market has pushed some private companies into the state-controlled category, because state investment funds now own significant parts of those companies.

The researchers tried to provide more clarity by detailed examination of the share of investment undertaken by private and privately-controlled companies. It shows the private share declined slightly in the first half of this year, but it is still the first decline recorded in the decade for which these data are available.

Real Economy, Real Problems

But private companies aren’t only being squeezed by policy, they are also being challenged by the market.

Like Zhang Qingli’s concerns over overseas orders, the Cheung Kong Graduate School of Business school survey also indicated that weak demand is by far the biggest challenge for the industrial economy, as reported by 81% of the firms surveyed in the second quarter. Some enterprises also cited concerns over labor and raw material costs.

“We heard about a lot of policy support for small companies, but they [only appear] in the news stories and not in real life,” said Zhang, complaining about lack of government and bank credit support.

Zhang said it is very difficult for small companies like his to get bank loans unless he provides hard collateral, usually in the form of real estate assets. Instead, he relies on retained profit and other sources to keep the business going.

John Wang, China manager of Corporate Value Associates, who has been consulting for Chinese banks for more than 10 years, says the banks do tend to favor state-owned companies.

“When the economy slows, it has a similar impact on state and private companies,” says Wang. “But to the banks, the private companies pose additional credit risks.”

Wang says that private companies may dress up their balance sheets, misappropriate the borrowed money or even transfer it to another company and bankrupt the current one.

“The bar for private companies is higher versus the state-owned companies even if they have similar operating results, cash flows, and collaterals, ” Wang says.

Possible Solutions

China’s top economic planning body, the National Development and Reform Commission, sent out a research team in May to look into the private investment slow-down problem, and then issued a work plan including 60 proposals. It mainly suggests that local governments improve services, help private companies to find funding and offer greater access to more areas.

But such structural reform pronouncements have yet to result in much real improvement. The government’s usual method of infrastructure investment to spur growth has not shown much effect in shoring up the broad economy this time, and has so far failed to encourage more private companies to invest.

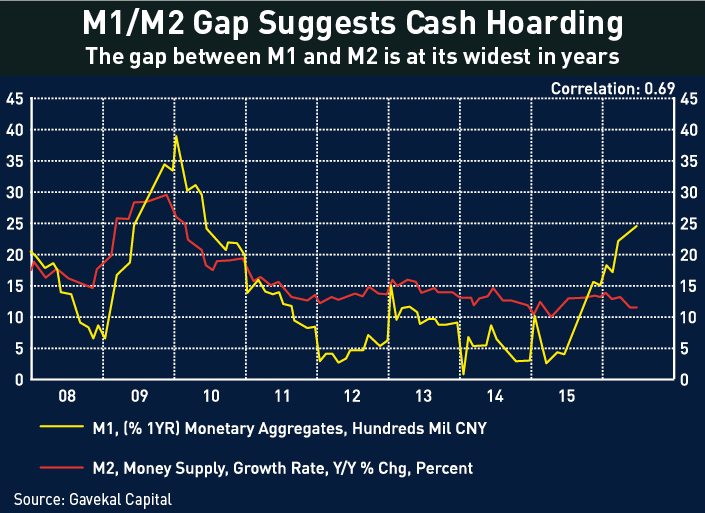

China’s central bank has been pumping money into the banking system, but analysts are concerned that much of the cash hasn’t been able to reach the real economy, or that companies that have spare money would rather hoard instead of expand their business.

Speaking at a forum in Shanghai August, Sheng Songcheng, the head of the central bank’s statistics department, said the gap between the growth rates of the narrower gauge of money supply, M1, and the broader measure of money supply, M2, had widened since October of last year largely because companies were having a hard time finding good investment opportunities.

China’s M2 slowed down to 10.2% in July year on year, the weakest pace in 15 months. The slowdown in M2 suggests that money isn’t being put to productive use. Rather, it is just sitting idle in corporate bank accounts.

What also worries analysts is that the high-flying property market has probably attracted too much liquidity from the real economy. Home prices are up about 60% in the past year in cities like Shanghai and Shenzhen.

“I plan to buy another apartment in my hometown where prices are expected to rise in the coming years,” said Zoe Chen, who owns an export company in Zhejiang Province.

Zoe’s company exports ink, and she says she has no plans to expand production.

“There aren’t many investment opportunities,” she adds. “If you invest into the products sold by the banks, they only offer you a return around 4%.”

In the first half of 2016, close to half of new bank loans were housing mortgage loans, according to the state media. While loans to non-financial enterprises have slowed, loans for fixed assets increased by 7.5% on year, 1.6 percentage points down on the first quarter.

Bright Spots

But not everything is doom and gloom.

“We are investing every year to update our manufacturing facilities to make our production more efficient and develop new products,” says Song Zhigen, whose company is a major stamp pad producer in China.

Song represents a group of business owners that believe they can continue to make decent profit by increasing efficiency and introducing new products, even if the industry they focus on has slowed down.

“The companies that produce automated equipment are very tied up recently, as so many manufacturers are replacing their facilities,” Song says, adding his company would invest at least half a million RMB for the same purpose.

Additionally, some industries in China are still expanding. Official data showed that private investments in electricity, heating power production and supply grew by 32.6% in the first eight months this year, while private investment in education increased by 15.7%, and 13.5% in auto manufacturing in the same period.

The speed of private investment also differs from place to place. Eastern China grew fastest, recording growth of 7.1% in the first eight months this year. It’s not a surprise as the area includes economically thriving cities and provinces like Shanghai, Jiangsu and Zhejiang.

But northeastern China has been a drag on the national economy, as the area’s private investment declined by 30.3% from January to August. Liaoning province even posted a 1.0% drop in GDP in the first half of 2016.

“Liaoning is a famous old industrial base in our country with most of its enterprises in commodity chemicals,” said Sheng Laiyun, spokesman with the National Bureau of Statistics. “In this round of readjustment, commodity chemical prices had the deepest correction, which posed downward pressure on Liaoning’s economy.”

Down but Not Out

China’s private investment isn’t slowing down all on its own, but rather along with the country’s economy as a whole. And while China is looking for reasons and solutions in the private sector, the real question is how to spark growth in general.

One solution under discussion would be for China to further reform its state-owned enterprises and allow the private companies to compete in more areas. There are also options like cutting taxes, launching favorable policies and sharing infrastructure construction opportunities with private companies more effectively.

Whether China can enact the right reforms to regenerate growth is an open question. The government is surly aware of the problem, but to carry out reforms to overhaul the system would mean cutting into the meat from the free lunches currently enjoyed by state-owned companies and local governments.

But ultimately, shoring up the confidence of entrepreneurs means the prospect of profit, either by raising expected revenue or cutting costs. The recent dip in the value of the RMB is helping export companies stay the course, but that’s not solid enough to encourage them to invest. They may see hopes rise if China can tame soaring property prices, control the rise in labor costs and make the government work more efficiently, which would all mean lower costs for private companies. But that is a tall order.

In the end, it might just be up to the market.

“Private companies invest for genuine demand,” says Liu Dongliang, “They retreat quickly when the broad environment worsens, and they will come back when the ice melts.”