How much sizzle remains in the world’s hottest tech startup scene?

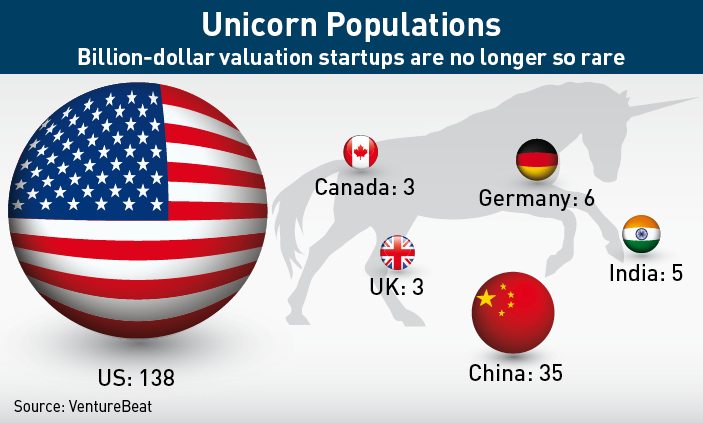

China has 35 tech startups valued at one billion US dollars or more, giving it the most ‘unicorns’ in the world after the United States, which has a whopping 138 of the once near-mythical companies. But 32 of the 35 have hit the billion-dollar valuation mark only since late 2014, and some observers see a bubble in the valuation surge.

China’s startup scene has long been the most vibrant in Asia. It has produced some of the most highly valued startups in the world, including smartphone vendor Xiaomi, No.3 at $45 billion, and ride-hailing service Didi Chuxing, No. 4 at $28 billion—although its value may balloon to $36 billion, if an agreed-upon merger with Uber China goes through. But the scene is now showing signs of frothing over as the world’s second-largest economy slows and traditional asset classes such as property and equities begin to lose their sheen.

Return-hungry investors of every stripe are pouring capital into young tech companies in sectors like online-to-offline (O2O), fintech and biotech. The Tencent-backed biotech startup Icarbonx, founded in October 2015, reached a $1 billion valuation in just six months, making it one of the fastest companies ever to reach unicorn status.

Simultaneously, Beijing is pushing supply-side reform in a bid to recalibrate the Chinese economy and turn China into an advanced manufacturing power, the goal of the “Made In China 2025” initiative. To succeed, Beijing will need more homegrown technology titans that can compete globally and the hope is that startups will play a key role in that endeavor. The combination of these factors has made for a lot of excitement.

“There is certainly a startup bubble, or a soon-to-be one, right here in China,” warns Stephanie Yan, head of the ZH Studio media consultancy, an experienced angel investor in China and a close watcher of the nation’s startup ecosystem.

And yet, for some, the money keeps rolling in. In January, Meituan-Dianping, China’s top restaurant booking and movie ticket platform, raised $3.3 billion from investors, including Tencent and VC firm DST Global, bringing its valuation to over $18 billion.

Yan concedes that China has a number of valuable, high-performing startups that are unlikely to falter. But she is concerned that with some institutional VCs tightening their belts and a glut of novice venture capitalists (non-institutional investors without a financial background) in the startup scene, Chinese entrepreneurs often lack a solid support system from their investors, “other than the money input.”

“No matter how much money they raise in round A or B, many Chinese startups usually cannot survive beyond round C,” she says.

The Story Behind the Chinese Tech Startup Surge

China’s startup frenzy began five years ago as fast smartphone adoption brought hundreds of millions of new consumers online. The most prominent company to emerge from that early pack of startups was Beijing-based Xiaomi, valued at $1 billion in December 2011, before most of China’s current unicorns were even founded. Notably, Xiaomi is a hardware maker, making the company an outlier—along with Shenzhen-based drone maker DJI—among the dozens of Chinese internet startups in the “unicorn club.”

Many of China’s top startups are in the online-to-offline (O2O) category, offering smartphone apps covering services like ride hailing, food delivery, and laundry pickup and drop-off. The demand for O2O in China is tremendous, observes Arthur Yang Zhang, a partner at the Sunnyvale, California-based Plug and Play Center, one of Silicon Valley’s earliest incubators, which provides resources for young companies.

“China lacks good service companies,” he says. “Big companies cover maybe half the market, which leaves a lot of opportunities for smaller players.”

And with China’s economy decelerating, startups are one of the few asset classes with strong growth potential. As a result, it has been easy for tech entrepreneurs to secure funding from China’s internet giants (Alibaba, Tencent and Baidu), venture capitalists and private-equity firms.

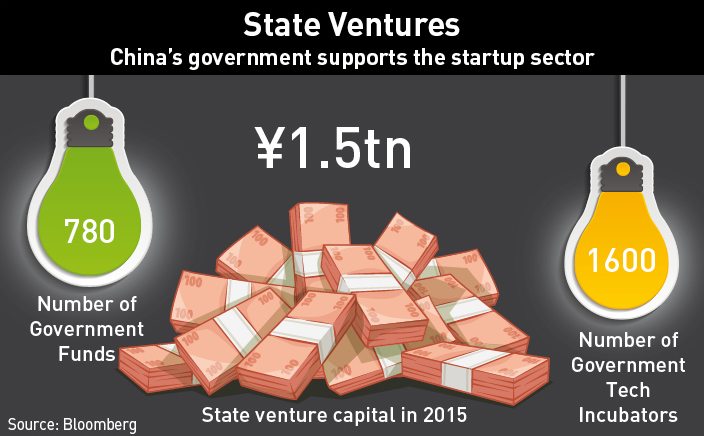

Beijing is providing further momentum as it seeks to reshape China as an advanced manufacturing power. As the offical annual GDP growth rate fell to a 25-year low of 6.9% in 2015, China’s state-backed venture funds raised about 1.5 trillion yuan (about $220 billion) in 2015, according to the research firm Zero2IPO. It is the largest fund pool in the world for startups.

“There’s a huge amount of money trapped in China because the government doesn’t want it to leave,” says Jamie Lin, co-founder of Taipei-based AppWorks, one of the largest accelerators in Asia. “There’s nowhere for it to go right now—except into startups.”

Much of the cash is contained in “government guidance funds,” which are operated by both central and local government agencies. There are 780 such funds, with tax revenue or state-backed loans providing most of their capital. To date, the government has yet to issue specific guidelines for how the funds should be managed, so experimentation is the norm, market observers say.

But government support for tech startups goes well beyond funding. Since 2014, it has also opened 1,600 high-tech incubators for startups. In May 2015, China’s State Council issued new guidelines to boost high-tech entrepreneurship. And in a June 2015 statement, it said: “It is imperative that we intensify structural reform, boost efforts to implement the strategy of pursuing innovation-driven development, and all institutional obstacles should be moved to give way to mass entrepreneurship and innovation.”

“Some people have argued that the government’s mode of support for startups is not conducive to nurturing an innovative, entrepreneurial ecosystem,” says ZH Studio’s Yan. “There’s some truth to that.”

Still, she acknowledges the positive role government-backed incubators on China’s eastern seaboard are playing. “Those organizations play very constructive roles as the early stage net for startups established by Alibaba and Tencent alumni, who personally told me that without these incubators and the VCs they helped bring in, they would have been less likely to launch their companies.”

The Chinese authorities “are directing where the market is going,” says Zhang, from Plug and Play Center. “Unicorns in China can only become unicorns because they are affiliated with prominent forces.”

Coming Down to Earth?

Meanwhile, the Chinese government has taken steps to ease overheating in the startup market. According to a May report by the Chinese-language business publication Caixin, the China Securities Regulatory Commission (CSRC) is moving to restrict firms in traditional industries from investing in tech startups, for instance by refusing to approve private share placements in a sector outside of a traditional firm’s core business. Additionally, the CSRC will more carefully scrutinize merger and acquisition activity involving traditional companies and tech startups.

Those moves come as more experienced investors are becoming more cautious. Compared to even a year ago, “there’s less hubris and more humility,” says Rui Ma, a partner at the Silicon Valley-based 500 Startups accelerator and the company’s head of Greater China operations. “For a startup at the early stage, it takes much longer to raise money. Investors want to know: What is the technology and IP [intellectual property] that you have that differentiates you?”

Plug and Play’s Zhang raises the example of the ultra-competitive and fragmented O2O fruit segment. “If you’re selling pineapples online, you better know exactly who your customers are and have cloud-based business intelligence tools to prove it to investors,” he says.

The upside of the market slowdown is that investors are less likely to back pedestrian business ideas in hopes of quick returns, which gives entrepreneurs more incentive to innovate, Ma observes.

Following several high-profile startup failures, “people are a little bit more cautious now,” Ma notes.

In March, the state-owned China Daily newspaper reported the Beijing-based e-commerce startup Metao was “facing imminent closure.” The news came as a surprise given the company had raised a total of $35 million from series A and B funding rounds in 2014 from prestigious VCs including Matrix Partners China and Morningside Ventures.

The Chinese-language Sina site reported in March that Metao founder Xie Wenbin was new to e-commerce and aimed to carve out a niche for Metao as a business-to-consumer platform offering heavily discounted products from overseas. Although Xie enjoyed some initial success, by 2015 he was ensnared in a head-to-head price war he could not win with e-commerce giants JD.com and Taobao. Metao never reached its Series C funding round, and was headed for collapse by late 2015.

Then in April, China’s official Xinhua News Agency reported the leading Shanghai-based grocery retailer Yummy77.com had filed for bankruptcy. Founded in 2013, the company received a $20 million investment from Amazon in 2014 that brought its valuation to $100 million.

Like Metao, Yummy77.com faced fierce competition from China’s e-commerce juggernauts, including Alibaba, JD.com and Yihaodian. Market insiders say Yummy77.com spent beyond its means on warehouse construction and a logistics network, and was unable to generate sufficient profits to offset those costs. A management team of online grocery retailing novices did not help matters.

Changing Fortunes

Those failures aside, to date none of China’s major startups have collapsed. But some market observers are beginning to wonder about the viability of China’s top unicorn, Xiaomi. Once the hottest rising star in the global handset market, Xiaomi’s sales have plateaued. It missed its 2015 shipment target of 80-100 million handsets by a wide margin, selling just 70 million units. In the first quarter of 2016, rival Chinese smartphone maker Oppo overtook Xiaomi in terms of units shipped.

Worse yet, Xiaomi is struggling to deliver its smartphones into the hands of consumers. The company’s strategy of negotiating low prices with its suppliers in order to reduce costs is taking a toll, observes Eddie Han, a smartphone industry analyst at the Taipei-based Market Intelligence & Consulting Institute (MIC).

“Suppliers see their prices and margins decline when they do business with Xiaomi, so some of them now prefer to work with other brands,” he says. As a result, “Xiaomi ends up with component shortages that put a dent in its shipments.”

Brand positioning is a problem, too. Han notes that Xiaomi is squeezed between the premium and mid to low-range market segments, offering little to distinguish itself. In the high-end market, for instance, Huawei is winning market share with “impressive hardware, such as a force-touch Leica camera or [a] homegrown high-end processor,” he says. In the low-end and mid-range market segments, LeTV and OnePlus offer top-notch smartphones for a fair price.

“It is hard to say whether this trend [of Xiaomi losing market share] is reversible,” he says.

As for Xiaomi’s much-touted internet-of-thing ecosystem, since it is likely to duplicate the same model used for its smartphone business, that is, the same concerns arise.

“Whether this will be the right move to make will depend on whether Xiaomi will be able to obtain enough revenues from content, services, and VAS (e.g. video, finance, online retailers, ads, and data analytics) and whether its suppliers will provide stable supplies to Xiaomi despite the decline in their margins,” Han says.

By contrast, Didi Chuxing’s prospects look considerably better. Its announcement in August to acquire Uber China’s operations eliminated its main competitor in China’s lucrative ride-hailing market, although the deal is currently surrounded by some regulatory uncertainty. Didi also has the support of the Chinese government, and is backed by a suite of heavyweight investors: Alibaba, Tencent, Softbank, Apple and ChinaLife.

AppWorks’ Lin says Didi Chuxing “is in a much better position than Xiaomi. I wouldn’t be surprised if in one year, Didi’s valuation is higher than Xiaomi’s.”

‘Late Summer’

Didi Chuxing’s case is not isolated: Many of China’s top startup companies have solid user bases and revenue streams, and some are profitable, notes Lin of AppWorks. He is dismissive of speculation about a tech startup bubble in the world’s second-largest economy.

“The situation in China now is completely different from conditions prior to the dot-com crash,” he says, referencing the infamous collapse of tech stocks in the early 2000s that wiped out over $5 trillion in market capitalization between March 2000 and October 2002. “There will be price corrections in the valuations of Chinese startups, but the risks are only borne by the companies and private institutional investors. The public isn’t involved.”

Critically, heavyweights in the global investment community remain sanguine about Chinese tech startups. In mid-July, veteran Silicon Valley investor Jim Breyer—known for his early investment in Facebook—and Chinese firm IDG Capital Partners announced they had raised a massive $1 billion VC fund in China, defying concerns about an overheated market. The new fund will invest in a number of industries such as technology, media, health care and energy.

According to data compiled by Dow Jones LP, the fund is the largest China investment fund backed by Breyer and IDG to date. Their investment collaboration in China dates back to 2005 and comprises seven funds including the most recent one. Accel Partners, Breyer’s former firm, collaborated with IDG on the first five funds, while the more recent two are between his new firm, Breyer Capital, and IDG.

In a statement, Breyer expressed admiration for “the caliber, creativity and drive of Chinese entrepreneurs working across a range of industries.” He added: “China continues to represent tremendous long-term investment opportunities, particularly in companies applying machine-learning and artificial intelligence to revolutionize a multitude of industries, including financial services, healthcare, and social media, to name just a few.”

Is he correct? To a certain degree, says Lin of AppWorks. “The China startup scene has reached late summer,” he says. “The heat has peaked, but the days are still warm.”