Chinese firms are betting on the acquisition of prime assets in the US and Europe to drive growth as the economy decelerates at home.

The Chinese economy grew by 6.9% in 2015, down from 7.3% in 2014 and the slowest pace in 25 years. The slowdown is likely to last as China works to change the fundamentals of its economy and transition from a reliance on investment to more sustainable growth driven by services and consumption.

In November 2015, speaking at the Asia-Pacific Economic Cooperation Forum, Chinese President Xi Jinping said: “We will work hard to shift our growth from just expanding scale to improving its structure.”

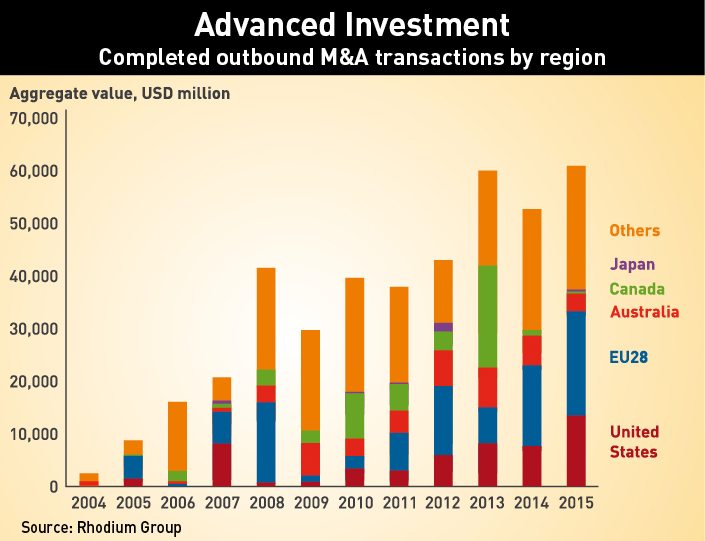

Overseas deal making is one way China is transforming its economy. Once used primarily to acquire energy and resources from developing countries, China’s outbound mergers and acquisitions (M&As) increasingly involve the acquisition of premium assets in the US and Europe.

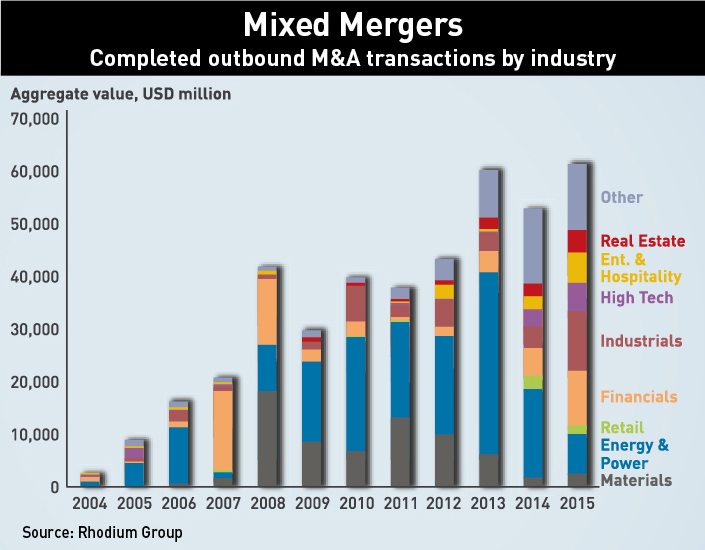

And while the Chinese economy decelerated at home last year, 2015 was a banner year for Chinese acquisitions. Chinese companies moved aggressively to capture premium global assets in a deal-making spree that drove China’s outbound M&A spending to an unprecedented $61 billion last year, up 16% from 2014, according to the Rhodium Group, a New York-based research firm.

“Many Chinese firms face limited growth prospects at home,” says Bee Chun Boo, a partner in the Mergers & Acquisitions division of Baker & McKenzie in Beijing. As a result, they are looking to acquire firms with advanced technology that they can later take back to China, reproduce at a lower cost and deploy in new products, she says. Once they have done so, “they are able to scale up those new assets on the back of existing customer relationships.”

In 2016, experts say China’s overseas M&A will accelerate as Chinese firms search the globe for premium assets to help them boost growth amidst the weakest domestic economy in a quarter century and a weakening yuan. The Rhodium Group forecasts outbound M&A spending by Chinese companies will rise to $97 billion this year.

“It’s going to be a very active year, and will most likely exceed 2015,” says Joel Backaler, Associate Vice President at the Frontier Strategy Group consultancy and author of China Goes Global, a book exploring the international expansion efforts of Chinese companies. “[In late January] there were nearly $10 billion in deal announcements in the US and EU: Wanda-Legendary ($3.5 billion), ChemChina-KraussMaffei ($1 billion) and Haier-GE home appliance ($5.4 billion).”

Deal flow continued to pick up in February as Swiss agribusiness giant Syngenta accepted a $43 billion cash offer from state-owned ChemChina. The deal, which would be the biggest Chinese takeover of a foreign company ever, is pending approval by Syngenta shareholders and regulators in Europe and the United States.

Powering Up

For years, China’s state-owned enterprises (SOEs) dominated its forays into global markets in pursuit of energy and resources. Their objective was to ensure China’s energy security—helping to negate fallout from volatile global commodity prices—at a time when its economy was growing exponentially. From 1990-2014, the energy and resources sector comprised 40% of China’s outbound M&A, by far the largest of any single sector, according to Boston Consulting Group (BCG) research.

“As the largest state-owned oil and gas firms in China interact closely with the government, they have a profound effect on governmental policy,” says Hongyi Lai, an associate professor of social sciences at the University of Nottingham’s School of Contemporary Chinese Studies.

Prior to ChemChina’s takeover of Syngenta, the largest overseas deal done by a Chinese company was China National Offshore Oil Corporation’s (CNOOC) acquisition of the Canadian energy company Nexen, valued at $15.1 billion. That deal has given CNOOC access to new energy technologies and the opportunity to operate in North American fields.

Yet deals like that are becoming less common as China makes structural changes to its economy, giving high-end manufacturing and the service sector a larger role. Just 20% of cross-border deals made from 2010-2014 sought to acquire strategic resources, while about 75% had the goal of accessing technology, brands and market share, BCG says.

To a certain extent, SOEs need time to consolidate the many assets they have bought in the past, observes Bee of Baker & McKenzie. “The need for them to do multiple deals has decreased,” she says.

Meanwhile, some observers say President Xi Jinping’s anti-corruption campaign has frightened SOE bigwigs, who are increasingly choosing to keep a low profile. “Among SOEs, there’s a desire to wait out the storm,” says Backaler of the Frontier Strategy Group.

Private Sector Ascendant

Since 2010, there have been a number of important deals by private-sector firms in the industrial goods, consumer goods, agriculture and technology sectors. An increasing number of deals are happening in the US and Europe, where Chinese firms can obtain “strategic assets” such as brands, distribution networks, technology and human capital, notes Lai of the University of Nottingham.

One of the most important of these deals was Chinese automaker Geely’s 2010 acquisition of Volvo from Ford for $1.8 billion, widely hailed as a major success. Geely has invested $11 billion in Volvo since the acquisition, helping the Swedish automaker’s annual sales to rise from 374,000 in 2010 to a record 466,000 in 2014.

Geely has benefited considerably from the deal. Buying a strong European auto brand known for the safety of its vehicles has allowed Geely to boost the quality of its own brands and make them more competitive in China—the world’s largest auto market.

“Geely CEO Li Shufu wanted to show the world that a Chinese company could maintain Volvo’s high standards—and they’ve been very successful,” says Backaler of the Frontier Strategy Group.

With the $4.87 billion acquisition of US pork giant Smithfield Foods in 2013, Chinese pork maker Shuanghui gained access to world-class hog processing and pork production technologies. Given the concerns of Chinese consumers over food safety, those technologies will help Shuanghui increase its competitiveness in the China market, according to a 2015 report by the International Food and Agribusiness Management Review.

The 2014 acquisition by Wanxiang, China’s largest auto parts maker, of US battery maker A123 was also important—for very different reasons, notes Backaler. Initially, US regulators had concerns that the “dual-use technology” used in A123’s batteries could have military applications. “Chinese investors I speak to are often concerned about acquiring assets in the US because they think the security review process is too difficult,” he says.

The security review process is overseen in the US by the Committee on Foreign Investment in the United States (CFIUS), an inter-agency committee chaired by the Secretary of the Treasury. It reviews transactions that could result in a foreign person controlling a US business to determine how those transactions could affect national security.

In September 2012, US President Barack Obama issued an executive order barring the Chinese firm Ralls Corporation from acquiring four wind projects located near a US naval facility in Oregon where drones are tested. The President did so based on CFIUS’ conclusion that the transaction could harm US national security. Ralls Corporation has itself to blame: it failed to notify CFIUS of the transaction until construction had begun, two months after the deal closed—and only at the request of CFIUS.

By contrast, with the assistance of its advisors, Wanxiang was able to assuage the concerns of US regulators, says Backaler. The Wanxiang deal showed it is possible for a Chinese company to successfully navigate the American national security review process when there is sensitive technology involved, he observes, adding: “I visited the A123 factory in Hangzhou last summer and it’s been a clear turnaround from a business perspective as well.”

Shop ’til You Drop

During China’s record cross-border M&A spree last year, one of the biggest players was Beijing-based Tsinghua Unigroup, the private-equity arm of Tsinghua University.

In the past two years, Unigroup has spent more than $9.4 billion in a quest to become a top global chipmaker. Its investments include the $3.8 billion purchase of a 15% stake in US data storage company Western Digital—the world’s largest hard-drive maker—and the purchase of a $600 million stake in Taiwanese chip packager Powertech Technology last year.

State-backed Unigroup is leading a drive by the Chinese government to build semiconductor national champions, a policy that could include up to RMB 1 trillion ($170 billion) in support from Beijing over the next five to 10 years. As a result, Unigroup is one of the few SOEs making bold M&A moves amidst President Xi Jinping’s ongoing crackdown on graft.

In November 2015, Unigroup announced it would invest RMB 300 billion ($47 billion) over the next five years in a bid to become the world’s number three chipmaker.

“Tsinghua Unigroup has demonstrated its grand ambitions to conduct aggressive M&A moves worldwide,” says Kevin Tu, a semiconductor analyst at the Taipei-based Market Intelligence & Consulting Institute (MIC).

For the Chinese, building a homegrown integrated circuit (IC) sector is “closely associated with national security,” Tu says, noting China’s current domestic IC production volume is low while demand is enormous. China is the world’s largest and fastest-growing semiconductor market, comprising 50% of the $336 billion global market in 2014, according to a 2015 report by the United States Department of Commerce. Yet demand so far outstrips supply that 91% of China’s semiconductors are imported, the report said.

The single biggest China outbound deal of 2015 was ChemChina’s purchase of Italian tire maker Pirelli for $8 billion, also China’s largest acquisition in Europe to date. ChemChina plans to combine the companies’ truck tire businesses and incorporate Pirelli’s expertise into its Chinese operations.

Meanwhile, HNA, owner of China’s fourth-largest airline, agreed in July to buy Swissport, the top global provider of cargo and ground handling services, from PAI Partners SAS. That purchase is expected to increase HNA’s access to a global aircraft leasing market where GE Capital and AerCap Holdings are dominant.

But for all the successes of China’s outbound M&A last year, there were some notable failures. Both Tsinghua Unigroup’s $23 billion bid for US chipmaker Micron Technology and the London Stock Exchange’s plan to sell its Russell fund management business to Citic Securities for $1.8 billion fell through.

No Deal

On average, Chinese firms complete just 67% of their outbound deals, which compares unfavorably with their European, Japanese and US counterparts, according to a September 2015 report by BCG research.

One of the impediments to China’s deal making is unclear M&A strategy. “Many companies lack a clear M&A roadmap, have only a vague idea of the purpose of any given deal and know little about the value of possible synergies or how to capture them,” wrote BCG partner Ying Luo in the report.

Unigroup’s failed bid to buy Micron indicates the Beijing-based firm’s interest in NAND flash chips, used on mobile devices to store music, photos and other data, says Samuel Tuan Wang, Research Vice President of semiconductors at Gartner and a 35-year veteran of the IC industry.

Yet an ill-defined strategy may have doomed that bid to failure, analysts say. “Over the years, Micron has shown it is determined to boost its market share in the memory sector with several M&As,” says Tu of MIC. “Therefore, it is unlikely Micron would want to exit the memory industry in this manner [a buyout by Unigroup].”

Given the association of the IC sector with national security, it is also unlikely the US government would have approved the deal, especially given Unigroup’s state backing, he adds.

Meanwhile, the London Stock Exchange Group’s attempt to sell the Russell fund management business to Citic Securities collapsed following investigations into the Citic management team. By December 2015, at least 10 Citic executives had been ensnared in a government probe into China’s July 2015 stock market tumult.

Once a deal has cleared regulatory hurdles, it can still be hamstrung by poor post-merger integration (PMI). Among Chinese firms, a common problem is the failure to develop a viable plan for the new entity’s organizational structure in advance of the closing.

“The post-merger integration phase is by far one of the most challenging aspects of cross-border M&A deals involving Chinese firms,” says Backaler of the Frontier Strategy Group. “Cross-border deals are always more complex, but when you take often relatively inexperienced Chinese buyers and they acquire companies in the US or EU, it’s all that more difficult.”

Cultural clashes can be heated. A notable case is the lease of Pier II of Greece’s Piraeus port by state-owned shipping giant Cosco. When the deal was announced in 2009, it was hailed by Greek officials as a much-needed investment in the sclerotic Greek economy that would boost Piraeus’s competitiveness. For Cosco, the pier serves as an important strategic gateway to bring Chinese goods into Europe.

Yet soon after Cosco took over operation of Pier II of the Piraeus port (Pier I is still operated by the Greek state-backed OLP Port Authority), Greek workers accused the company of mistreating them. The workers alleged Cosco forced them to work unreasonably long hours, failed to pay overtime and did not let them take a lunch break. Local union leaders warned Cosco was importing a harmful “Chinese labor model” to Greece.

Union leaders have observed frequent safety violations on the Chinese side of Piraeus, according to a December 2015 report by the Council For European Studies. For instance, crane operators work a four-hour shift—the maximum as stipulated by EU safety regulations—on the Greek side. But on the Chinese side, they work for eight hours. Additionally, union leaders say several accidents on the Cosco-run pier have gone unreported. They attribute those accidents to sub-par worker training, poor equipment maintenance, and a lack of safety precautions.

Learning From the Best

How then can Chinese firms become more adroit overseas dealmakers? “They need to be able to find the right assets, get them at the right price (not overpay) and be able to attract the best talent from around the world to run the acquired firms,” says Lai of the University of Nottingham.

At the same time, Lai urges Chinese firms to become more open, transparent and internationalized in their business practices.

To ensure greater success in cross-border deals, Bee of Baker & McKenzie says Chinese companies should involve advisors from an early stage. That will help Chinese firms be prepared to act decisively as slight hesitation can mean losing out to a rival bidder, she says.

Two cross-border deals done by Chinese firms stand out as exceptionally successful. The first is the acquisition by Mindray, China’s largest medical equipment manufacturer, of the patient-monitoring unit of US data science consulting firm Datascope in 2008. According to BCG research, Mindray is unusual for a Chinese company in that its M&A team consists of experienced deal counselors from global investment banks and law firms. Moreover, at each stage of a transaction Mindray has also clearly defined the roles of its management team, core M&A team and professional advisors.

By 2015, Mindray had become one of the top three companies in patient-monitoring systems globally and a leader in the ultra-competitive North American healthcare market.

The second—and most celebrated—example of a Chinese cross-border deal is Lenovo’s 2005 acquisition of IBM’s personal computing unit. Lenovo came to the conclusion it wanted to buy IBM after first launching a targeted global search for acquisitions, according to BCG. With its strong brand, technology, market channels and cost structure, IBM presented an attractive proposition to Lenovo.

The success of the acquisition has been clear: Lenovo achieved a compound annual growth rate of 41% from 2005 to 2015, BCG says.

After the acquisition, Lenovo adeptly integrated its own culture and IBM’s at the senior management level, and now a decade later, they have one of the most internationally diverse senior management teams of any Chinese company, notes Backaler of the Frontier Strategy Group. “This ‘global perspective’ only helps them be more successful as they attempt future acquisitions, as demonstrated by their successes including Medion, Motorola Mobility and IBM’s enterprise server division,” he says.

Lenovo has been prudent rather than opportunistic in its deal making, observes Tu of MIC. In the case of its 2014 acquisition of IBM’s server unit, “servers are not tied to national security in the same way as ICs,” he says.

Lenovo’s disciplined approach to deal-making is something for other Chinese firms shopping for overseas assets to consider. Over time, persistent failure to complete deals or smoothly execute post-merger integration could harm the global growth prospects of Chinese companies. Acquisition targets could grow wary of Chinese buyers—especially if they believe the buyer is not serious.

Tsinghua Unigroup should take note. Its informal $23 billion bid for Micron in July 2015 looked like a crass publicity stunt. Gartner’s Wang doubts Unigroup was sincere about the bid. Even if it was, cultural differences between the two companies “would have been extraordinarily difficult to bridge,” he says. “It would not be advisable for Micron to accept that deal.”

The offer was not serious, says Backaler, who spoke with a senior representative from Unigroup during during a site visit to Micron’s production facility the week that the bid made headlines in July 2015. That person said he did not expect the bid “to go anywhere beyond the headlines.”

“While many Chinese companies now have the cash to make high profile international acquisitions, what they often lack is the savvy and technical expertise to approach the deal in a way that is right for the overseas market,” he concludes.