China’s changing appetite is driving up the country’s food imports.

On a visit to France last year President Xi Jinping waxed Napoleonic by comparing China to a sleeping lion, which “has already awakened” but is, reassuringly, “peaceful, pleasant and civilized”. He might have added that she is hungry, as any examination of Chinese food imports since the turn of the century will demonstrate.

Until then, China largely fed itself. Yet the tables have since turned, transforming China into the largest food importer in the world. And as food prices have absorbed the implications, triggering occasional riots and revolutions in the poorer parts of the developing world, big international food exporters lick their lips.

As with most things Chinese, exponential growth and the seemingly unstoppable juggernaut of economic development encroach upon the boundaries of hyperbole. Changing food consumption patterns in China have seen increasing demand for foreign consumer food brands outpaced by even faster growth in demand for imported agricultural products and feed stocks.

This has happened despite a continuing stated policy goal of food self-sufficiency. The result has been an evolution in land use within China, greater integration of Chinese state-owned enterprises (SOEs) in global wholesale markets and a subtle shift of emphasis away from self-sufficiency within China, towards prioritizing the security of the Chinese supply chain. And while this fast growing market provides many opportunities for foreign food companies, the political sensitivity of food will ensure conditions apply to their uptake.

Iron Rice Bowl

Food has always had a political dimension. For ancient city-states like Athens or Rome, securing food imports from the Black Sea and Egypt became vital imperial priorities. China, by comparison, has always fed itself, the ability to do so providing a measure of government or dynastic legitimacy through the ages. In pre-reform China the ‘iron rice bowl’ referred to the daily food allowance of workers, but came to symbolize the protected benefits of state employees, such that accession to the World Trade Organization (WTO) meant committing to ‘breaking the iron rice bowl’ and ensuring the market played a greater role in employee compensation arrangements.

In practice, joining the WTO has also meant China participating directly in world agricultural markets, and laws of comparative advantage ensure food cost advantages accrue to more mechanized economies with a relative abundance of arable land, like Australia, Brazil and, most of all, the US.

Although in retrospect China’s growing demand for food must have seemed obvious, it wasn’t always so. Steve Martin, from Shanghai Ying Jie International Trading Company Ltd, recalls his first encounter with Australian investment in the Chinese food sector from about 1990. “When I first started doing food industry work, our primary market was Japan, and it was like ‘China’s where? There’ll never buy anything’,” he says. “I got the opportunity to send a team of technical people to China Great Wall (China’s largest domestic wine producer). My boss absolutely pooh-poohed it. He just laughed [and said], ‘They’re not going to drink wine.’”

Needless to say, despite China’s history of self-sufficiency, there is a remorseless logic in the fact that China has 20% of the world’s population and only 9% of the world’s arable land. And it is a logic that cultivates a particular sensitivity among China’s strategically minded elite. Being dependent on foreign imports of anything creates vulnerabilities; food especially so. In 2014 China imported $122 billion worth of agricultural products, more than the entire value of imported copper ore, motor vehicles, aircraft and pharmaceuticals combined.

Water, Water Everywhere

Nor do the potential supply constraints end there. China Water Risk, a non-profit initiative focused on highlighting water risks to business and investors, estimates that due to rapid industrialization nearly half of China’s rivers, reservoirs and ground water supplies don’t meet the standards for human use. In 2011 China’s Ministry of Environmental Protection estimated that approximately 10% of China’s arable land, or 1% of all arable land in the world, was polluted with heavy metals.

Of course, water has many uses, and the costs of clean water can simply transfer an economic burden from agriculture to energy or industry. But Debra Tan, Director of China Water Risk, says, “If you don’t have water, you have no food security.” Food security depends upon water security, which in turn, due to the heavy need for water in the energy sector, depends upon the energy mix, an area where China also has a high level of insecurity. So until China gets its energy policy right, aspirations for food security may be unrealizable, leading Tan to conclude that China’s obvious water constraints will continue to act as a driver for food imports: “We’re still bullish on food imports.”

Equally important is that water usage clearly remains a priority for the Chinese government, which, in April published an umbrella plan dubbed the ‘Ten-point water plan’ which sets out a range of high level measures to address water pollution in China, establishing an ambitious target date of 2020 for a sustainable water use equilibrium.

Beyond this, the question of climate change is also expected to exert some temporary pressure on food imports. In 2012 Tang Huajun, Vice President of the Chinese Academy of Agricultural Sciences estimated that, due to climate change, China is set to experience a period in which basic crops will be insufficient to meet demand in about 2030.

However, despite some regional concerns within China, the country as a whole is seen as relatively resilient to the effects of climate change, and due to a forecast population decline will find itself back in surplus before 2050. That being said, the uncertain global impact of climate change on overall agricultural production can only reinforce the perceived need for China to address the question of food security over the long term.

Home Growing

Nevertheless, it is easy to overlook the considerable growth in domestic food production recently. Matthew Crabbe, Director of Research, Asia Pacific at Mintel Group, says, “One of the great untold stories of the last years has been the real shift or improvement in agriculture in China.”

This matters because in the long run, as Steve Martin says, “Much as everyone would like to think that Tasmania is going to become the agricultural bread-basket of China… they will send high-end product, nice quality onions and such like, but really, at the end of it, when you are talking about those sorts of crops, they end up being grown locally.”

Martin suggests that although it has become commonplace to see China’s food imports growing ever larger, it is to some extent up to China how long this goes on for. “Growing an onion is not rocket science. All it is is better varieties, better horticultural techniques—it will be easy to pick up… [and]… in the longer term, food growing will be improved,” he says.

Nicholas Hunt, Asia representative of Harvest Road, the agricultural division of Western Australian commodities giant Minderoo, agrees. “It will develop. Their production per hectare will increase. Their productivity will increase.”

Tan, however, thinks supply constraints will hold China’s agricultural production back for a long time: “Until there is rural land reform, you’re not going to see the sort of tonnes per hectare that you do with large scale farming in the US.” Although on a more optimistic note Crabbe says, “as the government has shifted attention towards the environment, that can only encourage more domestic production.”

A Moveable Feast

Despite the longstanding rhetorical commitment to food self-sufficiency, however, the Chinese leadership have been relaxing definitions for years. The most significant change was a semantic shift away from ‘grain self-sufficiency’ towards ‘edible grain self-sufficiency’, which propelled imports of feed grains such as soybeans to almost 85% of demand in 2014.

The ‘key grains’ of wheat, rice and corn remain supported by price floors, which sustain production above 95% of domestic consumption. Nevertheless, this focus on edible grain production still distorts land-use by prioritizing total production over efficient production. In February 2014 Beijing accepted the inevitable and shifted the focus of domestic production towards quality and food safety over quantity by stipulating a simple grain target of 550 million tons for 2020, well below estimated domestic demand of 720 million tons and indeed below the 2014 harvest of 607 million tons.

All of which merely reveals how it is changes in Chinese consumer food demand that have surpassed expectations, not only of Australian food producers in the 1990s, but the Chinese government as well. Equally, the US Department of Agriculture (USDA) estimated in 2000-2002 that accession to the WTO would increase US exports of agricultural produce by $900 million, to about $1.6 billion annually; in 2013 the actual figure was $25.9 billion.

Feeding the Masses

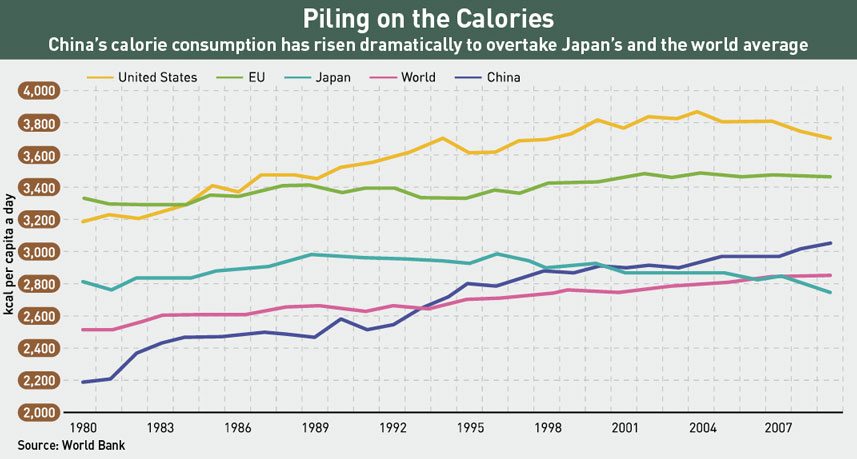

The whole story of Chinese food imports ultimately comes back to a poorly anticipated rise in consumer demand. According to the World Bank, Chinese average daily calorific intake has increased from 2,163 to 3,036 per person between 1980 and 2009.

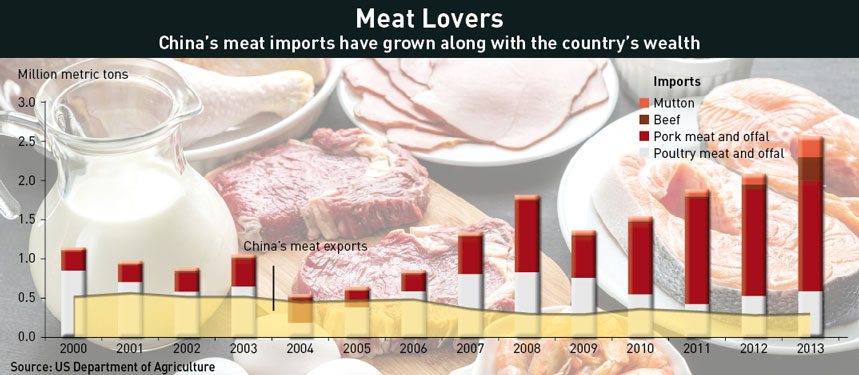

Yet behind these numbers lies an even larger increase in what is known as ‘cereal equivalent’—meaning the amount of cereals used to produce the calories—which has more than doubled over the same period, due to the increase in chicken, pork and beef production from 20 million tonnes in 1986 to 70 million tonnes in 2012. The knock-on effect on world food prices is hard to estimate but, for example, the raised price of feedstock attributed to Chinese imports accounted for about half the 23% increase in the price of eggs in the US in 2011, according to an American farmer quoted in a Tampa Tribune article that year.

And although Chinese agricultural production has also risen steadily over the same period as it has slowly modernized, it still has a long way to go to catch up. In the meantime it is the big, flexible agri-businesses in the rest of the world that have been best placed to meet fast rising Chinese demand. Nicholas Hunt sees the value of China’s imported food market very clearly. “We’ll look at any opportunity but the really big ones are beef and sheep, grain, wheat for flour, barley for beer… live-export, dairy, not just fresh milk but yogurt.”

Indeed, Harvest Road is a relatively recent addition to Minderoo group’s longstanding China-focused iron-ore export operations, representing a horizontal diversification strategy premised upon China’s increasing appetite and the premiums this offers to large-volume foreign producers. “There was a belief by the owner, Minderoo and Andrew Forrest in particular, about the long-term opportunities in Asia. Harvest Road has Harvey Beef [acquired only 12 months ago]. But it’s also got a big milk business, fresh milk out of Western Australia… [importing] into China in particular.”

In February 2015, the USDA published a major report highlighting that China was now both the number one export market for US produce, and that the US was the largest supplier of produce to China, identifying the soybean as the key commodity. Soybeans feed China’s growing livestock herds as average diets incorporate ever more meat, but growth in imports have also risen across the board.

Safety First

Unfortunately, this rising Chinese consumer demand seems to be directed towards imports for more reasons than simply scarce land and the slow pace of agricultural productivity improvements within China. All recent consumer surveys conducted in China reveal the plain truth that consumers prefer foreign branded products if they can afford them, a fact driven by the scandals that hit the Chinese food industry with alarming frequency. Historically, foreign brands have had a prestige value for gift giving, but as incomes rise, expensive foreign brands become affordable for more everyday consumption.

“Even the taxi driver in Shanghai, tells me that if he can afford it, for his children, he buys imported food products, and only from foreign companies,” says Hunt. He adds that trust is so low consumers “won’t [even] buy from a Chinese company that says it’s imported.” Of course, most people don’t have the choice as “imported stuff is really expensive,” says Hunt, who estimates that “Australian beef is four times more expensive than Chinese beef.”

“Many food companies have improved the quality of their products, but they still face this barrier of perception. People still think that because it’s Chinese it must be inferior,” says Crabbe, adding that, “one of the major stumbling blocks is questions about the quality of the food, some of which comes down to perceptions about the environment. That’s one of the real issues for China right now, is to clean up the environment.”

But for Hunt, the problems are starker: “I can’t get over the collapse in trust for domestically produced food… I have little confidence that they will solve their problems.”

King Consumer

Crabbe, however, complicates the picture somewhat: “More Chinese people are travelling abroad and being exposed to new things, then sharing that information online through social media,” indicating that consumers in China are increasingly sophisticated. “They are being exposed to many more products outside of China” which “has led to Chinese people actually buying foreign foods online, if they can’t get it in their local stores.” All of which suggests that it is not solely a question of fear that is driving demand for foreign produce, but also curiosity as China opens up culturally, as well as economically.

And with this increasing consumer sophistication has come the slow integration of China’s food wholesalers into world markets. On the one hand, this rhetorically satisfies a re-imagined criteria of self-sufficiency, which extends to the vertical integration strategies of China’s SOEs and is part of the wider ‘go abroad’ strategy, yet on the other hand is just Chinese wholesalers seeking the same product premiums enjoyed by strong foreign food brands in China, while responding to the evolving tastes of their customers.

All of which goes some way to explaining the recent high profile acquisitions by Chinese SOEs of large foreign food producers, like the 2013 Shuanghui-Smithfield deal, valued at $4.7 billion. Or indeed Shanghai-based Bright Food, which famously bought UK cereal brand Weetabix in 2012, after having swallowed Australian food group Manassen in 2011, and which has since moved on to acquire the Israeli dairy producer Tnuva this year.

In this, Chinese companies have an advantage over large foreign importers because they have much better access to the established distribution networks within China, but as long as Chinese consumers will pay a premium for imported food, there will be strong competition to capture those premiums.

For the time being, however, there is plenty of demand to go around, and rather than take on Chinese suppliers in their home market, most foreign food suppliers prefer to “do business with China, not in China”, says Hunt. Such an approach has been given a boost by the use of Alibaba’s e-commerce platforms for the purpose of selling foreign fresh food—in June, Jack Ma, Executive Chairman of the company, touted Alibaba’s work with American farmers in a Wall Street Journal op-ed.

All the trends behind China’s rising food imports look set to continue for now, reinforcing the impression of increasing food dependence for China. The Chinese government is, however, gearing up to ensure that China will eventually be able to feed itself again on its own, although that is still some way off.

Given the increasingly global nature of food markets, for now the task of feeding Xi Jinping’s lion actually boils down to ensuring global supply rises with global demand. Which in turn means understanding that the decisive factor behind rising Chinese food imports is a long term evolution in consumer demand rather than shorter term supply constraints, informing a strategy of facilitating the global integration of food suppliers and not underestimating Chinese appetites again.

China’s long-term food priority will inevitably remain to feed itself, even if that means buying overseas supply chain. In the meantime their appetite for imported food, and the difficulty of improving the quality and safety of their own agricultural products, may yet see China continuing to eat everyone else’s lunch, because for the time being, they don’t much like the look of their own.