Does China’s debt, which refuses to stop growing, threaten to take the show off the road?

For years, China’s economic growth has surged ahead even as that of more advanced economies has stuttered in the wake of the financial crisis, spell-binding pundits and economists around the world. But this period of prodigious growth has also seen the emergence of an issue that also bedevils developed countries—debt.

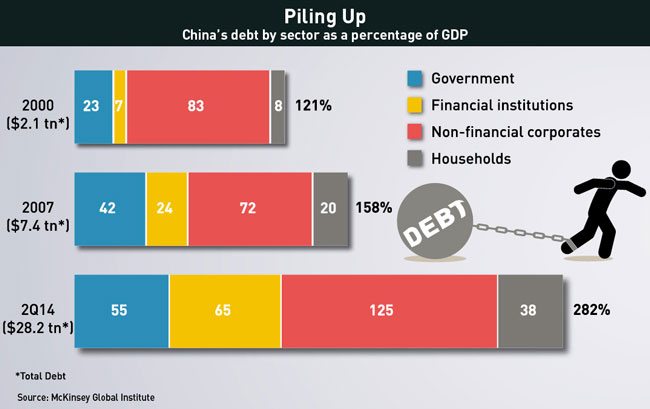

Since 2007, China’s total level of debt—encompassing that held by the government, households, financial institutions and non-financial corporates—has quadrupled and now represents 282% of GDP, a higher percentage than that of Germany or the US, according to a McKinsey Global Institute (MGI) report released in February.

In the eyes of some economists, China may be approaching an inflection point. Now, as growth slows and people are being encouraged to come to terms with a so-called “new normal”, there is a sense that in addition to the ongoing and difficult process of systemic reform, the country’s debt issue may soon come to a head. Should Beijing continue to pile on the credit in the hopes of sustaining growth with the risk that it is simply creating a greater reckoning later on? Or should it cut back and face the potentially deleterious consequences?

Turning on the Taps

As with many contemporary economic tales, the latest chapter of China’s debt story has roots in the aftermath of the financial crisis. As countries around the world reeled from its impact, particularly those that were key export markets for China, the central government was forced to unleash a massive stimulus, lest the external tumult create a crisis in China too.

But there were earlier entries in the narrative of debt build-up as well. The first was the changes to local government finance rules in 1995 that constrained their ability to raise funds. As a result, the wave of China’s infrastructure projects that formed a large part of the 2008-09 stimulus package had to be financed by local government through debt. The second plot line came from China’s long-building property boom throughout the last decade, which saw developers take on increasing amounts of debt.

Nonetheless, it was from 2007 that the real build up in credit began. From then until mid-2014, China added $20.8 trillion to its debt, more than one-third of global debt growth, according to MGI. In that time, only Greece, Portugal, Ireland and Singapore saw a greater increase in their debt-to-GDP ratio. If China’s debt were to continue to increase at the same rate as it did in that time period, China’s debt-to-GDP ratio would be the same as Spain’s, 400%, by 2018.

Although its ratings are currently stable amongst the big three credit ratings agencies, in April 2013 Fitch downgraded China to A+ from AA-, where it currently remains, citing “underlying structural weaknesses” and concerns that rising debt would require a bailout. Fitch had previously issued a downgrade warning in 2011, but this was the first downgrade of China by a major international agency since 1999.

What Lies Beneath

Much of China’s debt is, directly or indirectly, linked to real estate—MGI puts the figure at 40-45% of all loans, or equivalent to $8.5-9.5 trillion. These loans encompass homeowner mortgages, property developer debt, lending to related industries and debt raised by local governments for the purpose of property development.

Moreover, many loans come from the shadow banking sector, with credit coming from informal loans, wealth management products, entrusted loans between companies and other sources. By its very nature the shadow banking sector lacks transparency. Nonetheless, such loans are estimated by MGI to be worth $6.5 trillion, or 30% of China’s debt when excluding the financial sector, and they grew 36% per year from 2007 to mid-2014.

Demand for these loans is primarily driven by small companies that otherwise find it hard to access funding and by investors looking elsewhere for high-yield investments as a result of low bank deposit rates.

Of government debt, much is held by local governments. They possess little taxation authority and much of what they do raise flows to the central government. In addition, from 1993 up until last year local governments had been banned from borrowing directly. As a result, many were forced to turn to so-called local government financing vehicles (LGFVs) in order to pay for the vast infrastructure projects that have proliferated around China. Local governments are also heavily exposed to the property sector due to their reliance on land sales as a way of raising cash.

The numbers, however, aren’t necessarily straightforward, both in general terms and specifically for local government debt. It is hard to get a complete and accurate picture, and Jianguang Shen, Chief Economist at Mizuho Securities Asia, notes how local government debt is often packaged as corporate debt instead. “Sometimes they classify LGFVs as [the corporate sector]. They have to because Chinese law does not allow local government entities to borrow.”

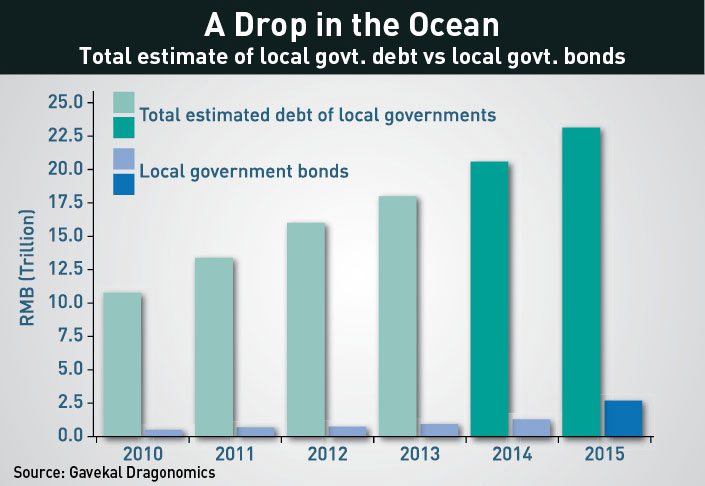

As such, the true extent of government debt has for many years been unclear, and only now is some transparency being introduced through government audits. These concerns are why the Chinese government actually conducted two big surveys in 2010 and 2013, says Shen. “In 2013 they found out the total local government debt actually amounted to RMB 18 trillion ($2.86 trillion),” he says.

Dragged Down?

The nature of this debt is problematic for several reasons. One is its strong connection to the property market, which after years of growth showed signs of overheating early in 2014. Since then the market has begun to witness a correction as a result of government policy, lagging sales, excess inventory and slowing price rises. In the event of a severe downturn in the market many companies would default, with potentially serious knock-on effects. And even without a serious downturn, some developers will still be at risk.

“The property sector is [a] sector where we worry [about a default],” says Li-Gang Liu, Chief Economist for Greater China at ANZ. “In addition to high leverage, this anti-corruption campaign will also push certain privately run property developers into default.”

The opacity and lack of regulation in the shadow banking sector is another area of concern. Despite lacking the complexity of the pre-financial crisis financial products that nearly brought down the banking system in the US, there are questions over the risk assessment capabilities of lenders, as many are forced to invest in speculative real estate and high risk borrowers in order to achieve the high yields that investors are looking for.

But thankfully, there has been a slowdown in shadow banking activity. “The shift in credit flows back to the regulated banking system should enhance transparency and reduce financial risks, but it could also create pressure on some borrowers, such as small and medium-sized enterprises and small property developers who are reliant on the shadow banking sector,” Michael Taylor, Moody’s Chief Credit Officer for Asia-Pacific, said in a press release from the agency.

Of greater concern to some economists is local government debt. “I think the biggest risk definitely is the LGFV debt,” says Shen.

The strain that some local governments are under was indicated in March when the government of the southern city of Haikou revealed it was unable to make its debt repayments and needed financial assistance. Despite that claim, the provincial government, Hainan, and Finance Minister Lou Jiwei were both quoted at the Boao Forum (a high-level annual forum in China modeled after the World Economic Forum) as saying that local governments were not at risk of defaulting.

The slowdown in the property market feeds heavily into these difficulties. Many local governments are reliant on land sales in order to make loan payments, but as the market has cooled, these are no longer lucrative or reliable sources of income. Just how serious this has become was brought into sharp relief in January after the Financial Times reported on the farcical situation of local governments in some provinces, such as Jiangsu, buying their own land in order to push up prices.

The risk posed by local government debt also stems from the fact that defaults would be felt throughout the banking sector—the China Development Bank and the Big Four banks (Bank of China, ICBC, China Construction Bank and Agricultural Bank of China) all have significant exposure, according to MGI. A November 2014 Standard & Poor’s report stated half of China’s provincial governments would be below investment grade if rated.

Wider economic factors play a role in determining the threat posed by China’s debt, too. The country is witnessing slowing inflation, which in turns exacerbates debt levels as the debt is no longer depreciating as quickly. The slowing economic growth further constrains the ability of firms to pay back loans, particularly if growth in debt remains strong, and increases the risk of defaults as companies struggle with China’s current economic transition.

In addition, China’s debt service ratio—principal and interest payments as a share of income—is very high. According to the Bank of International Settlements (BIS), it is now 9.5 percentage points above its long-run average, and BIS has specifically identified this as presenting a risk since a greater share of income is being required to pay off debt, and so the economy is less able to handle extra credit. A 2012 BIS report found that debt service ratios can provide an accurate warning of future bank crises.

Going to the Wall

For years there has been a perception that the government would guarantee loans, creating a moral hazard whereby investors feel they will be bailed out should a default occur. That has only served to encourage risky lending. Nonetheless, the government has committed to allowing the market to play more of a role in this area, for instance at the Third Plenum, where it was announced that market forces would play a “decisive” role in the economy. But their willingness to do this is already being tested.

In March 2014, Chaori Solar, a solar equipment producer, became the first mainland company to default in China’s domestic corporate bond market. In the end, investors were bailed out through a debt restructuring plan in October, with the government being heavily involved through the Great Wall Asset Management Corporation, indicating the limits of the government’s rhetoric, and also their desire for stability.

Since then, other companies have joined the ignominious list of defaulters. In April, Cloud Live became the first company to default on its principal, and later that month the property developer Kaisa defaulted on interested payments on its offshore debt after lengthy attempts to restructure and a 30-day grace period. Rounding off the list of companies with credit woes that month was Baoding Tianwei Group, the first state-owned company to default on an onshore bond.

“This is probably a good thing for China’s corporate bond market,” says Liu. “The government will break down the moral hazard so that investors will have to be careful in investing in those corporate debts. I think perhaps more such defaults will be seen, but the government will also very careful not to cause a systemic risk for the Chinese financial system.” He also points out that significance to the local economy and employment will be important factors in the government’s thinking as well, and this may explain the attitude towards letting Baoding Tianwei default.

Shen agrees that such defaults will be closely managed. “I think the [Baoding Tianwei default] will be quite isolated,” he says. “I don’t see a chance of massive bankruptcies by state-owned enterprises (SOEs).”

So Serious?

But for all the scale in China’s debt situation, two facts weigh heavily in its favor: manageable amounts of household and central government debt. “Although local government and firms are overly in debt, the Chinese central government and households are very limited in debt, and this is a very positive picture,” says Liu.

Not only does the government have vast foreign currency reserves at its disposal—although it would be reluctant to tap into them—MGI puts the amount of central government debt at 27% of GDP, giving it ample room for borrowing. For those reasons, the government is well positioned to handle a bailout, should the need arise—even with a default rate reaching 50% for property-related loans, such a bailout would still be viable.

“The central government’s direct debt is only 15% of GDP, so that’s why there is huge room for the central government to absorb and actually help local governments,” says Shen.

Moreover, government control of the financial system gives the government much scope for action. “China still has a mainly state-owned financial system… the government, the central bank, the People’s Bank of China (PBOC) and other regulators can jump in quickly,” says Liu.

But complications remain.

Changing Vehicles

The central government still faces the onerous task of converting local government debt into something more sustainable, transparent and manageable. To that end, LGFVs were outlawed in October by the State Council, China’s top decision-making body, although they later backtracked in May for cases involving ongoing projects. Still, a prior change to the budget law in August 2014 had finally allowed for local government bonds.

“People actually expect something like municipal government bonds, but in the end I don’t think it’s real government municipal bonds,” says Shen. “Still it’ll have to be under tight control by the state, by central government. So actually they need to approve these bonds, and also it’s more or less guaranteed by the central government… the major issue for me is the central government is using its balance sheet to borrow more to pay for the LGFV debt.”

In order to deal with maturing debt, in March the Finance Ministry announced that local governments would be allowed to issue RMB 1 trillion in long-term, low-interest bonds to pay off maturing loans. According to the ministry, these bonds are equivalent to 53.8% of municipal loans that need to be repaid in 2015, and Finance Minister Lou has indicated that the program will likely be expanded.

Questions have been raised about who will buy these bonds, although others remain confident there is a market for them. “The special debt replacement bonds will likely be bought by banks and other institutions,” wrote Tao Wang, Chief China Economist at UBS, in an April report. “Given the general abundance of domestic saving and controls on bank lending, there should be sufficient domestic liquidity and demand for local government bonds, and there is no need for the central bank to purchase them.”

But, apart from the big four state-owned banks, uptake has not been as strong as expected, and some provinces have delayed issuing bonds. But in response to the reluctance on the part of commercial banks to buy the bonds due to their low yields, the PBOC will let banks use the bonds as collateral for key lending facilities in order to make the bonds more attractive.

Overall, though, many analysts are optimistic about the bonds’ prospects, and expect the program to be expanded. “Fitch expects the extension of the municipal bond issuance program to allow [local and regional governments] to smooth out revenue volatility and improve their liquidity during this period of slower economic growth and weakness in the property market,” the agency wrote in March.

Further Action

Government support for the beleaguered property sector is also on hand. Although prices and sales continued to decline in the first few months of 2015 in many cities, market sentiment has shown signs of improving, in part because of government measures to stabilize the market. In March, regulators moved to lower requirements for down payments on second homes from 60% to 40%, and reduced the number of years homeowners are required to hold a piece of property before they can gain exemption from a sales tax.

There are also wider steps the government can take in order to control the level of debt in the country. One of these is reform of SOEs and Shen feels that this is also an area ripe for government action when it comes to scaling down China’s debt.

“A private company, if you’re losing money, then mostly they’ll be closed down, so there is a limit to how much they can borrow, and also for most private companies bank lending is very difficult to get” he says. “The issue is mainly the SOEs… they borrow a lot of money, but even if they have a problem paying, the government will always step in and ask the bank to lend them money. So that’s rolling over and getting more and more debts.”

Shen says that SOE reform had been expected in order to introduce transparency in this area, but that this has been “postponed”.

Instead, he identifies the stock market, which in Shanghai has witnessed an extraordinary rally in recent months, as playing an important role in addressing the issue of SOE debt. “We think the new government strategy is to boost the stock market,” says Shen. “It can reduce the debt burden of the corporate sector. So the SOEs, they don’t need to borrow from the banks, they can issue equity.”

In the final tally, China is unlikely to face a Lehman-style crisis as a result of its growing debt, largely due to the government’s firm grip on the financial system and its own relative lack of debt.

But the build-up of this debt in China will provide a test of the government’s willingness to embrace the market and to push ahead with reform, particularly in areas it has hitherto treated with a light touch, such as with SOEs. As things shake out, some firms will no doubt suffer, as the likes of Kaisa have already begun to discover.