Robots may promise a bright future for manufacturing, but a darker future for workers

Over the past 25 years, China has become the world’s preeminent manufacturer, churning out everything from running shoes to Apple products. Powering that ascent was heavy foreign direct investment and a seemingly inexhaustible pool of cheap labor.

But now as the Chinese economy slows, wages rise and the workforce atrophies, the decades-long manufacturing boom may be ending. In 2015, Chinese exports fell for just the second time since the launch of economic reforms in 1978. Wages for China’s 277 million migrant workers rose 7.4% to RMB 3,072 per month ($473), while the number of working-age people fell by a record 4.9 million, according to the National Bureau of Statistics (NBS).

Deteriorating conditions have prompted some foreign businesses to reduce their China exposure. The annual China business-climate survey published in early 2016 by the American Chamber of Commerce in Beijing found that 25% of respondents have either moved or are planning to shift capacity outside of China. Half are those going to developing Asian countries, and another 40% to the US, Canada or Mexico.

To help deliver China from industrial decline, the Chinese leadership is betting on automation. Large-scale deployment of industrial robots could raise efficiency and lower costs, channeling the resources of China’s vast supply chain. While some workers would be replaced, new ones—albeit fewer—would be needed to design, construct and operate the manufacturing machines.

“Robots will be a game changer for the Chinese economy,” says Chiang Chia-wei senior analyst at the Taipei-based Market Intelligence & Consulting Institute (MIC), an IT industry analysis provider in a written reply. “Smart manufacturing is an essential part of China’s industrial transformation and bid to increase its global competitiveness.”

At a 2014 speech at the Chinese Academy of Social Sciences (CASS), Chinese President Xi Jinping noted a “robot revolution” is underway globally. The worldwide market for industrial robots surged from 60,000 units in 2009 to 248,000 units in 2015, according to the International Federation of Robotics (IFR), an industry-lobbying group, and since 2013, China has been the world’s No. 1 buyer. The IFR reckons that China will overtake Japan to be the world’s top operator of industrial robots by the end of 2016.

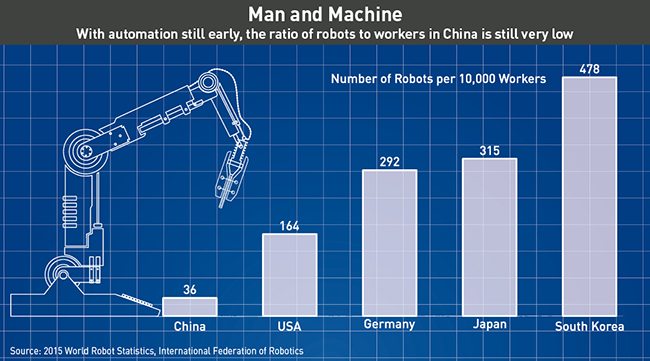

Robot penetration, however, remains relatively low in China. In 2015, that figure was just 36 per 1,000 manufacturing workers, 28th in the world, according to the IFR, although that does mean there is a lot of room for growth.

But although China will likely be the leading market for robots for a long time, it faces technological challenges. Japan, the United States, and Germany remain the pioneers of the industrial robot industry, according to MIC.

But Beijing intends to directly challenge the world’s current global robotics leaders. “We not only need to upgrade our robots, we also should capture markets in many places,” President Xi told the CASS audience.

Robots assemble a Cadillac near Shanghai

Automation Drive

China’s ambitious robot plans in some ways echo Chairman Mao Zedong’s call in 1958 for China to overtake Britain in industrial production within 15 years. This time, the objective is to channel the productivity acumen of millions of robots to surpass Japan, the US and Germany in terms of manufacturing prowess by the centennial anniversary of the People’s Republic of China in 2049.

“Amid the continued growth of industrial robots, the MIIT (Ministry of Industry and Information Technology) has taken an aggressive stance towards robot development, making it one of the key strategic industries in China,” says Chiang.

In March, Chinese authorities approved the China’s 13th Five-Year Plan, a policy blueprint, which highlights the importance of industrial automation and makes available billions of RMB to upgrade manufacturing technology. The drive includes “Made in China 2025,” a state-led initiative to make China an advanced manufacturing power within a decade, of which automation is a big part.

“If they can automate enough of their lines, China’s production and revenues could expand another 25% by 2025,” says Gerald Van Hoy, a senior research analyst at IT research firm Gartner in Oregon.

Progress toward automation is already moving at a good clip in both the public and private spheres. In 2015, Guangdong province, long China’s top manufacturing hub, pledged to spend $150 billion to install industrial robots in its factories and establish new advanced automation centers. And this July, China’s top 10 robot manufacturers formed an alliance dedicated to research and development of advanced industrial and service robots.

All the efforts seem to be bearing fruit – the output value of China’s domestic robots reached RMB 1.64 billion in 2015, up 55% over a year earlier, according to the Qianzhan Industry Research Institute.

Yet for now, it remains difficult for China to develop indigenous high-end robots.

“The domestic robot industry has a short history—it really only began in 2000,” says Jing Bing Zhang, the Singapore-based research director of IDC Worldwide Robotics, at the market research firm International Data Corporation. “The base is still very shallow.”

Not surprisingly, then, MIC’s Chiang says that about 70% of robots used in China are produced by global brands.

“While the market is lucrative, Chinese companies lack the ability to develop homegrown components and have to largely rely on imports,” he says. “This is why the government has taken such an aggressive stance to foster its homegrown robotics industry over the years.”

As a result, the acquisition of foreign technology through M&A deals has become integral to China’s robotics strategy.

Overseas Shopping Spree

To hasten their climb up the value chain, Chinese firms are buying up premium robotics assets overseas. In January, China National Chemical Corp, Guoxin International Investment Corp, and Chinese-European private-equity firm Agic Capital purchased German industrial robot maker KraussMaffei for $1 billion. In April, Zhejiang Wanfeng Technology Development Co purchased the US’s Paslin Co, an automotive assembly-line robotics manufacturer, for $328 million. And in June, Agic Capital announced its acquisition of Gimatic, an Italian supplier of end-of-arm tools for industrial automation and robotics applications, for 100 million euros ($108 million).

“The motivations behind those three major acquisitions made by Chinese buyers are deeply rooted in their wishes to obtain technological strength and gain system integration experience from those foreign companies to help them develop industrial robot components at a faster pace,” says Lin Yi-ching, an industry analyst at MIC. “For those foreign companies, they have been given a great opportunity to set foot in China.”

Shenzhen-listed Siasun Robot & Automation Co., China’s biggest robot maker by market value, whose customers include General Motors, Ford and Schneider Electric, also has plans to acquire global robotic component manufacturers. At a robotics fair in Munich in June, Siasun president Qu Daokui said the company is hunting for acquisition targets in Europe. According to Chinese media reports, the company plans to raise 2.96 billion yuan ($449 million) from five institutional investors in November.

The most notable acquisition of the year is appliance maker Midea’s $5.1 billion bid for Germany’s Kuka, one of the world’s top-four industrial robot brands and an employer of 12,000 people globally. Kuka plays a crucial role in Germany’s Industry 4.0 initiative, which aims to connect the physical factory with the virtual world.

“Acquiring Kuka will help Midea obtain key component manufacturing technologies that Chinese manufacturers lack, while Kuka can take advantage of Midea’s strong channels in China’s domestic market,” says MIC’s Chiang. That should help Kuka expand its 15% share of the Chinese industrial robot market.

Yet the deal has also raised concerns that it will provide China with undue influence over Germany industry. In a June interview with Financial Times, Markus Ferber, a German member of the European Parliament, said he worried a technology outflow from Germany to China was occurring, which would mean “the cars of the future” might be built in China rather than Germany.

To add to that, European policymakers and businesspeople are expressing growing frustration with the restrictions Beijing places on foreign companies in China. In its 2016-17 Position Paper published in September, the European Chamber of Commerce in China noted: “Chinese companies have successfully completed a number of eye-catching deals to acquire leading European companies in a wide range of areas—including banking, automotive, robotics and critical infrastructure—yet European business is still heavily restricted from making similar investments in China.”

Not So Fast

But trade tensions aside, while acquiring premium global robotics assets will certainly boost China’s robotics industry, it is not a solution in itself. In the view of MIC’s Lin, the main reasons China lacks the ability to develop critical robot components such as controllers, decelerators, and servomotors is because it lacks corresponding patents and technologies that are still held by a handful of advanced countries. Of 3,794 industrial robot patents reviewed in a report by MIC this year, 61.3% are owned by Japan, 17.9% by the United States, and 9.7% by Germany—a combined share of 88.9%. By contrast, China holds less than 1% of industrial robot patents.

However, acquiring them through M&A or other means is also not an instant fix.

“It still takes time for their manufacturing capability of those three key components to become world-class in terms of reliability, hardness, and fineness,” says Lin.

Gartner’s Van Hoy notes that this issue has rather far-reaching consequences in terms of the whole industry.

“China currently has a problem sustaining the robots it has already installed,” Hoy says. “When a robot breaks down or malfunctions it stops the line until someone qualified to work on the robot arrives. This can take a while, particularly in Western China where infrastructure may be an issue.”

This is not to mention that there is also a shortage of trained personnel to operate and maintain such advanced machines. “It takes time, even in a crash-course approach, to get enough intelligent people into those positions,” Hoy says.

Considering those issues, robot oversupply is unexpectedly a problem, especially because of the generous subsidies Beijing is doling out to local governments. According to Shanghai-based market research firm Innova Research, 32 robot industry parks had been planned or established in China by municipal governments in 14 provinces as of the end of August this year. Richard Jun Li, a vice president at the company, said in a statement: “At this stage, thirty-two robot industry parks are probably too many. The oversupply on the robot industry park spaces will likely result in the elimination of quite a few of these parks.”

A July report in Bloomberg News noted that scams to capture subsidies for robotics projects are on the rise. Citing the Chinese-language Economic Observer, the report said a number of companies with negligible robotics experience have received large cash handouts that are not being used for their intended purpose. Most egregiously, one company in Nanjing attributed 65% of its 2015 net profit to robot subsidies.

Age of the Machine?

The bigger issue of automation is less technical: How to handle the potential displacement of large numbers of Chinese workers?

In May of this year, news broke that Taiwan-based contract-manufacturing giant Foxconn had replaced 60,000 of its employees with robots at a facility in Kunshan, a city near Shanghai. Foxconn later denied that it had laid anyone off, and generally downplayed the idea of automating away its employees, but still told the BBC, “We are applying robotics engineering and other innovative manufacturing technologies to replace repetitive tasks previously done by employees.”

Regardless of Foxconn’s current robot/human employment situation in Kunshan, a robot-induced rise in unemployment is a real threat to China. It is happening elsewhere already, albeit on a smaller scale. In July 2015, the English-language version of the People’s Daily reported that a factory in Dongguan operated by the Changying Precision Technology Company (a manufacturer of electronics components) had replaced 590 of its 650 employees with robots.

The remaining 60 workers monitor production lines and a “computer control system,” it said, noting that productivity in the factory had increased threefold with the added robots while the product defect rate had plunged. By July 2017, the company says it expects to have 1,000 robots at work controlling 80% of its processes.

Roughly 100 million people work in the Chinese manufacturing sector, which contributes nearly 36% of China’s gross domestic product, but IDC’s Zhang believes Beijing is prepared to manage the transition.

“I’m sure the government is aware of the problem and I would expect they have a plan to provide new opportunities for employment,” he says, noting that increased automation will create jobs for higher-skilled workers such as robot programmers and technicians. How such a plan will work in practice, however, remains to be seen.

Chen Ching-kuo, a worker in a Taiwan factory of German high-tech polymer manufacturer Covestro, says he is unworried in the short run about losing his job to a robot. Chen is responsible for the dyeing of running-track materials, and converting those materials from a liquid to solid form.

“I don’t think it would be that easy for a robot to do what I do, at least not yet,” he says, adding that he does not think his company would hastily replace its human employees. “They [Covestro] have always been good to us.”

To be sure, robots will not replace all manufacturing jobs. They are best suited to replacing jobs involving repetitive tasks. Humans will still be needed for jobs that require judgment, common sense and creativity.

Yet China faces a dilemma: As its workforce ages and shrinks, an ever-increasing number of robots will be necessary to maintain productivity levels and keep manufacturing costs competitive. But the speed at which China needs to replace workers is likely to be faster than its ability to manage their redeployment.

But if China does not automate production fast enough, it ultimately risks losing its prized status as the world’s factory. For manufacturers, “there is a lot of attractiveness to staying in China. It’s a huge market, the consumers are there,” says IDC’s Zhang. “But automated manufacturing in the US and Europe is eroding China’s cost advantages.”

He concludes: “China is prioritizing industrial robots because it has no choice. If it does not take action, the supply chain will leave.”