MSCI’s inclusion of China stocks is a big opportunity for foreign investors, but risk management is tricky.

In June, MSCI announced that it would include select mainland China stocks in its indices. The move, although initially small, gives a big legitimacy boost to Chinese markets—but how do the markets work and what risks do they entail?

After years of hesitation, MSCI finally agreed in June to include mainland China stocks in its global benchmark equities indices. The decision means Chinese stocks will become an increasingly important part of many investor’s portfolios in the future, and on the news, China stocks immediately soared to an 18-month high.

MCSI creates the stock indices behind some of the world’s largest exchange-traded funds (ETFs). With the investment world increasingly moving toward ETFs, every passive asset manager pegged to an MCSI index where China is included will now be obliged to buy mainland equities, known as A-shares.

“We believe its strategic importance (MSCI’s decision) lies in the fact that it will likely transform China A from a ‘nice to have’ to a ‘have to have’ market, and redefine how global equity investors think about their opportunity set and capital allocation over time,” Goldman Sachs wrote in a July report.

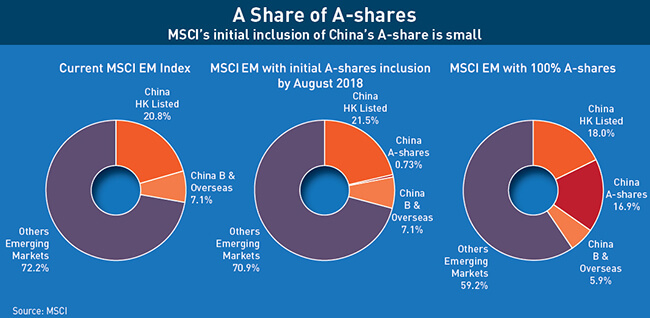

For Beijing, the decision marks a milestone in efforts to draw international funds into the world’s second-largest market, but also indicates how much more regulators need to do to open the country to the world. MSCI will take only 222 of the largest and most liquid mainland-listed companies starting from May next year. These stocks will account for less than one percent of the market capitalization of the MSCI Emerging Markets Index.

MSCI’s caution is not without basis—China’s currency is not fully convertible and mainland markets are a long way from being market-driven. This means investors who track the indices must factor in extra risks.

Taking Stock of the Market

China’s equities market was re-established in 1990 with the founding of the Shanghai Stock Exchange and Shenzhen Stock Exchange. Today, the Chinese stock and bond markets are now the second and third-largest in the world, respectively.

China now has more than 3,000 listed A-share (RMB-denominated) companies, and 100 B-share companies (denominated in dollars), more than double the number in 2007. China’s market capitalization totaled RMB 39.9 trillion ($6.2 trillion) as of May 28, up from RMB 5.9 trillion ($915 million) in May 2007. For comparison, the New York Stock Exchange’s market cap was $21.3 trillion in June, and the Hong Kong Stock Exchange HKD 30.7 trillion ($3.9 trillion) in early September.

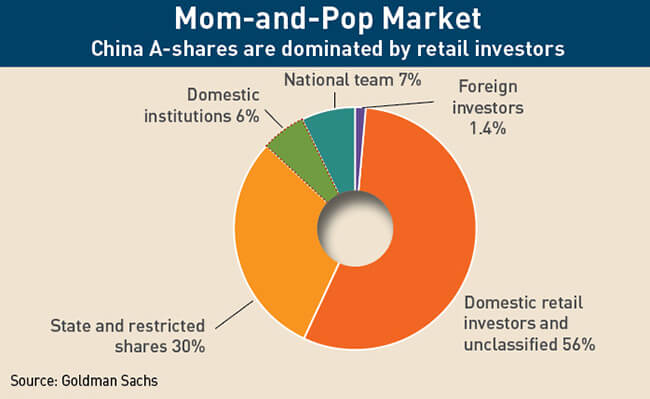

Trading on the two mainland stock markets is dominated by “retail investors,” speculative mom-and-pop players notorious for get-rich-quick and in-and-out trading habits that drive market volatility. This makes China different from developed markets where professional institutional investors play the leading role.

“If you look at market cap, retail investors own around 50%,” says Amy Lin, Senior Strategist of Capital Securities, the first Taiwanese securities firm to open an office in mainland China. She notes that in the past few years, the balance has been shifting toward institutional investors. “But retail investors may still make up 70% of daily trading as institutional investors don’t trade so actively.”

The details are more complex. Goldman Sachs’s research shows 69% of shares on the Shenzhen Stock Exchange are owned by retail investors. In Shanghai, it is only 45%. On the Hong Kong Stock Exchange, for comparison, local retail investors constitute 20% of daily market turnover, according to the stock exchange itself.

In other major markets, trading largely results from investors assessing the impact of economic trends and specific company results. Not so in China, where trading by retail investors tends to be driven by rumors and politics. The most important factor underpinning China’s markets is the implicit guarantee that authorities will step in and resolve any major problems.

“Markets have a casino characteristic that has a lot of appeal to people, particularly when they see people getting rich around them,” investment legend Warren Buffett told CNBC in May, referring to China’s stock markets. “Those who haven’t been through cycles before are more prone to speculate than people who have experienced the outcome of wild speculation.”

For some astute traders, the disproportionate number of retail investors is a benefit. “In my experience, the strong retail participation is good for professional fund managers because it makes the market more inefficient,” says Chris Ruffle, portfolio manager with Open Door Investment Management Ltd, who has more than 20 years’ experience investing in China’s stocks. “Retail investors read the newspaper, then they buy this and that. If I go out to visit the companies and really understand them, then I will be in a better position.”

Inexperience, short-term mentality and “herd behavior” makes for dangerous markets—as seen in the harrowing crash of the Shanghai stock market. After several years of hovering above the 2,000-mark, the Shanghai Stock Exchange Composite Index began rising in December 2014, peaking and then crashing in June 2015.

The stunning surge was caused by several factors, including falling borrowing costs, a clampdown by the government on property investment (one of the few other investment options available in China), central support for stock investment and relaxed rules on margin trading (borrowing funds on margin from brokers to play the market). According to Goldman Sachs, formal margin lending alone accounted for 12% of the market float at the peak and 3.5% of China’s gross domestic product.

By June 2015, the Shanghai market hit a seven-year high of over 5,100, more than double its value half a year previously. Observers voiced concerns that the rise was driven by speculation and not fundamentals, particularly given that the overall economy was slowing. Half of the companies on the exchange were priced at 85 times their earnings. The bubble burst on June 12, and in three weeks the market shed about 30% of its value. By early October the Shanghai Stock Exchange was down to 3,000.

The National Team

Such volatility spooks professional investors, but what is more concerning is the level of government intervention. As the market began to crumble, authorities embarked upon invasive measures to stop the slide. There was ban on selling by major corporate shareholders and an outright trading suspension of almost half of listed companies. The government also directed companies to buy back their own shares with finance provided by state banks whenever it was needed. Not long after, the Ministry of Public Security announced that it would arrest “malicious” short sellers.

Billions of RMB were injected into markets, particularly through the “national team,” a coalition of state-owned financial institutions—but almost to no effect. On August 23, more than two months in, the government announced that it would allow China’s state pension fund to invest up to 30% of its RMB 3.5 trillion ($527 billion) into equities in another effort stop the bleeding. The market recovered slightly topping out at 3,600, but fell again in January 2016 to below 3,000. It has since then slowly climbed back to over 3,300.

Patrick Chovanec, Chief Strategist at Silvercrest Asset Management and former Professor at Tsinghua University, wrote in Foreign Policy in 2015 that, while the intervention may help to put the brakes on collapse, it undermined confidence in market principles. Echoing an infamous remark from the Vietnam War, the piece was titled, “China Destroyed its Stock Market in Order to Save It.”

This August, the China Securities Regulatory Commission (CSRC) lifted many of the emergency measures in place since the crash, noting that the stock markets had “achieved smooth operation,” after a “period of abnormal fluctuation.” The long-term impact of state-backed investment funds, the National Team, in the stock market has, however, been profound.

While some thought the National Team’s participation might end after the market stabilized, it has become a major player and now holds an estimated 7% of the entire A-share market, according to Goldman Sachs. Indeed, the state bought so much stock that it became the majority shareholder of a number of private firms, effectively converting them to state assets.

And the National Team has developed its own patterns of investment. “The investments they hold are relatively long term, big cap and value-driven, which could serve to stabilize the market to some extent,” said Hao Hong, Research Head with Bocom International Holding Co.

Although emergency restrictions are lifted, others remain. In major international markets, companies can conduct an initial public offerings (IPO) whenever they meet the exchange’s conditions, but in China, the CSRC has strong grip over new share supplies.

Companies that want to go public need approval and may have to wait in line for years. In bad seasons, IPOs are stopped entirely to avoid weighing down the weak market. The CSRC then resumes approvals when the market recovers. It approved 225 initial public offerings in the first half of 2017, more than double the number of a year ago.

The CSRC also caps IPO prices at 23 times a given company’s historical earnings, aiming to prevent more volatility in the secondary market. Taken together, these factors create unique conditions. “A-shares can be inscrutable, with a different trading environment that international fund managers will find hard to adapt to,” says Hao Hong.

Gradual Opening

The China A-share market was first cautiously opened to outside investors in 2003. Under the Qualified Foreign Institutional Investor program (QFII), selected foreign institutional investors can invest in China’s stock markets with significant restrictions. It was in effect an early effort at internationalizing the RMB. Early QFII players were big names such as UBS, Morgan Stanley and Goldman Sachs and the list has gradually expanded since.

In late 2014, the door opened wider. The launch of the Shanghai-Hong Kong Stock Connect scheme allowed equities on the Shanghai Stock Exchange to be purchased through the Hong Kong Stock Exchange by foreign investors, and for mainlanders to buy stocks in Hong Kong. A total of $3.4 billion flows between the two exchanges each day, with no daily quota on individual accounts. Unlike QFII, the stock connect program requires no special license for trading and investors can repatriate funds without restraints.

In December 2016, China extended the program to the stock market in Shenzhen, again allowing $3.4 billion in daily trading. Currently, more than 1,400 A-shares can be accessed via the Stock Connect program of the 3,000 listed A-share companies. Trading volume through the scheme has picked up steadily with the volume from the mainland constituting 5% of the Hong Kong market’s turnover in April, according to a Hong Kong Exchange report.

The real achievement of the Stock Connect was to lay the groundwork for MSCI’s decision. MSCI will essentially be building on top of that. The A-share inclusion into MSCI will take place as a two-step process in May 2018 and then later in August. By August, China A-shares will account for 0.7% of the MSCI Emerging Markets Index.

The initial list of 222 comprises stable, large-cap companies are not dominated by China’s infamous retail investors. They are some of China’s most important names—China’s “Big Four” banks, China Life Insurance, Petro China, distiller Kweichow Moutai, automaker BYD—and are also largely state-owned enterprises.

However, some of China’s most familiar (and profitable) companies will not be included—such as the “BAT” tech trio of Baidu, Alibaba and Tencent. They are listed on the Nasdaq, the New York Stock Exchange and the Hong Kong Stock Exchange respectively.

This does not mean that there will be a lack of investment opportunity. “If you want to find the biggest industrial companies in their own markets, you can find several in China, like auto, wine and milk,” says Amy Lin. She adds that these companies are offering generous dividends and stable growth.

Right Choice?

MSCI’s decision to include A-shares in its indices was the result of immense pressure applied by Beijing after the reforms of the Stock Connect program. But numerous problems remain, as does heavy state oversight of the market.

One issue is trading limits on A-shares, which are only allowed to rise or fall by 10% on a trading day. Not only are there restrictions on price fluctuations, but A-shares are suspended from trading far more often than on other global exchanges.

Reuters reported that during the month of July this year, an average of 265, or one in every 13, listed companies in China suspended trading for some period, with the number of suspensions rising 30% from an average of 202 in January.

This prompted MSCI to issue a warning to China barely a month after the announcement of index inclusion. “If we find a company suspends for a long time, over 50 days, we will remove it from the index, and we will not bring it back to the index again for at least another 12 months,” MSCI’s Head of Research for Asia Pacific, Chin Ping Chia announced.

Some recent suspensions resulted from trading volatility—usually smaller companies hitting the pause button to avoid a price crash. But the number of suspensions of larger companies has also increased as Beijing steps up consolidation of state-owned enterprises. This hints at another problematic aspect of a state-controlled market.

State-owned enterprises are not purely profit-driven; they also have significant responsibility to support government policy (see article page 30). They ultimately answer to the Chinese Communist Party before they answer to any other shareholders, to say nothing of foreigners.

Another issue is China’s capital controls and the ability of investors to get their money out of the country. Although investors can currently repatriate funds, there is no guarantee that will always be the case. In fact, there is precedent for the China rolling back promises.

Soon after the RMB was added to the basket of Special Drawing Rights currencies defined by the International Monetary Fund (IMF) in October last year, China tightened its capital controls, upping the scrutiny of companies and individuals moving money out of the country. The move was seen as an indication that the IMF had acted too soon, and some analysts expressed concern that the situation may be repeated in the stock market.

“MSCI have broken their own standards just to shoehorn China in, as the IMF did with the SDR,” says Michael Every, Senior Asia-Pacific Strategist with Rabobank Hong Kong. “There are many things negative about the decision, because China has not met key criteria and there is no real evidence that it can avoid a future repeat of 2015’s market drama going forward—to say nothing of its problems with debt, housing, capital controls and political risk.”

New Era

China’s inclusion into the MSCI indices marks a new era in China’s emergence as an accepted part of global equities. Although the market capitalization weighting of each of the initial company stocks is only set to 5% of its market cap, MSCI will consider increasing all to 100% should market reforms continue. It will also consider including the remaining 226 or so companies in the future.

This is a huge carrot to dangle before Chinese authorities who desperately want their markets to be more widely owned outside the country. Global investors keen to get involved in China will, however, need to accept the local equities market for what it is—a highly speculative government-controlled but growing market.

The size of the money flows that follow the MSCI decision will reveal how acceptable that is. By MSCI estimates, $17 billion to $18 billion could initially flow into China from the initial inclusion of mainland China stocks.

“I think anybody can see that… eventually China will be entirely included,” says Ruffle, noting that when this occurs, China will be over 50% of the Emerging Markets Index. “My contention is, over the next five to 10 years, China will emerge like a strict asset class, a bit like Japan in the 1980s. It won’t be a sub-sector of the emerging market, but a stand-alone sector like America and Europe.”