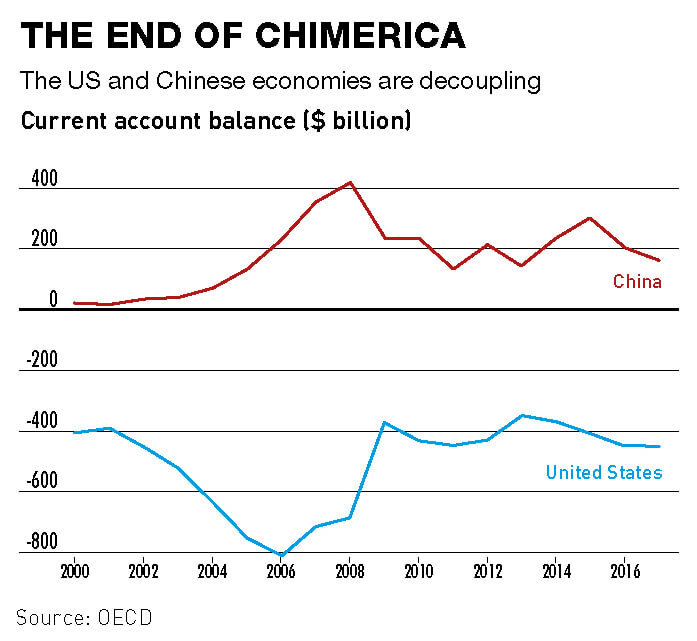

Despite a record trade surplus with the United States, China could soon be running a current account deficit. What would this mean for the global economy?

In early August, just as the United States was escalating its trade war with China, the release of a surprising set of economic data briefly threw the media debate off course.

Since February, attention had been focused on China’s $375 billion trade surplus with the US. President Donald Trump had repeatedly pointed to the massive surplus as evidence that China was a mercantilist power “ripping off” America.

But on August 6, China’s State Administration of Foreign Exchange released figures that complicated this narrative. The country’s current account, which is effectively determined by its overall balance of trade in goods and services, dipped to a deficit of $29 billion for the first half of 2018. Though China is still “ripping off” the US, it is also now being ripped off by the rest of the world.

The move into deficit underlines the fact that China’s economy is undergoing fundamental changes that will have impacts far beyond its borders. A decade ago, China’s huge current account surplus was the symbol of its status as the “factory of the world.” The surplus surged following China’s entry into the World Trade Organization in 2001, reaching a peak of 9.9% of gross domestic product (GDP) in 2007.

But in recent years, that surplus has been steadily shrinking. Last year, it sank to 1.3% of GDP. The half-year deficit announced in August was the first in more than 20 years.

Seasonal factors mean that China may not post an annual deficit this year, but some economists think that it is only a matter of time before it does. Deutsche Bank predicts a Chinese deficit by 2020.

If that happens, it will be a watershed moment with implications for all manner of issues, from the policies Beijing is able to pursue to the status of the RMB as a global currency and maybe even the way the US finances its debt.

“When a country moves from a long era of surpluses to a deficit, it’s a bit like a regime change,” says David Lubin, Head of Emerging Markets at Citi. “The market has to go through a process of developing a new understanding of how the economy works.”

Yet there is still uncertainty over how the trade balance will develop over the next few years—not least because of the policies being pursued by the White House.

Political Data

There are two very different schools of thought on how to interpret China’s fall toward a current account deficit. Some economists, including Zhang Jun, Dean of the School of Economics at Fudan University in Shanghai, fit the decline into the broader story of China’s development.

“The fundamental reason is the policy shift in China, which some call the rebalancing of the Chinese economy,” says Zhang. “From 2008, Chinese policy toward the macro-economy changed a lot. The focus has been on raising the level of domestic aggregate demand.”

Rising consumption will almost inevitably lead to higher demand for imports, and an economy of China’s size would normally be expected to start running a current account deficit when it transitions to a consumption-led growth model, according to Zhang.

There is plenty of evidence suggesting that this is happening. The national savings rate has fallen over the past decade, though it still remains high at 46% of GDP, and household consumption is rising faster than GDP. Goods imports are increasing twice as quickly as exports. Most importantly, there has been a surge in overseas tourism, which has sent China’s services deficit ballooning from $15 billion in 2011 to $265 billion last year.

“When you look at why the current account balance has fallen, it’s because of tourism,” says Lubin. “It’s almost literally a one-word explanation.” He adds that travel accounted for some 85% of the net services deficit over the past five years.

According to this logic, a deficit is more or less inevitable in the long run as China moves toward a new economic model. “The paradigm shift has already happened,” affirms Zhang.

But some analysts argue that the growth model has actually changed much less than the current account figures suggest. The fall in the trade balance has been driven, at least in part, by more contingent factors.

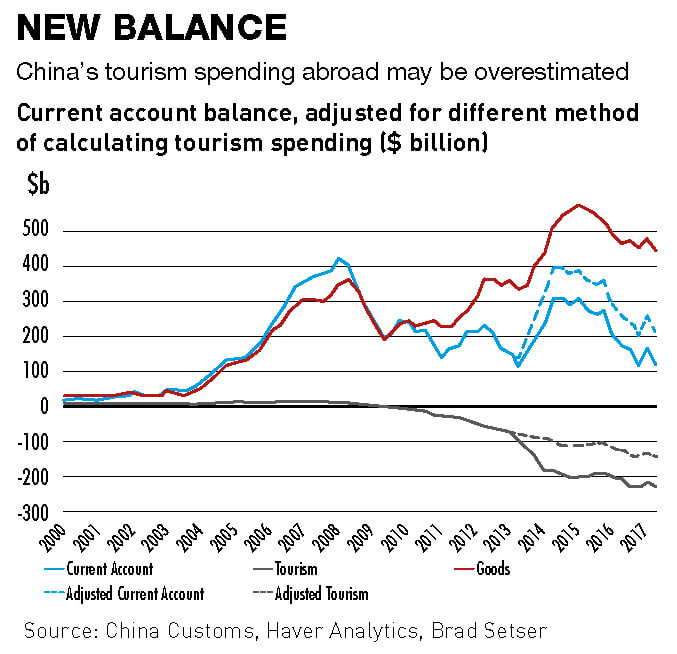

Brad Setser, a senior fellow at the US Council on Foreign Relations, points out that China’s goods trade surplus, though falling, remains large at $421 billion. And a significant driver of the decline has been rising global prices for China’s top two goods imports: crude oil and semiconductors.

China’s spending on foreign oil rose 39% year-on-year to $162 billion in 2017, while semiconductor imports rose 13.9% to $259 billion. If prices for these products were to fall, the trade surplus could start expanding again.

There are also questions over the services deficit, which may be smaller than it appears. The huge leap in tourism imports recorded in 2014 was primarily the result of a change in the way China calculates spending data. This switch in methodology may even have been intentional.

“Let me put it this way. At the time, due to the fall in oil prices, China’s current account surplus was soaring,” says Setser. “The timing was certainly convenient.”

Overall, Setser believes that China’s current account balance is undervalued by between $50 billion and $120 billion. If that estimate is correct, it would suggest that there has been a structural shift in the Chinese economy, but it has been slower than official data implies. By extension, China could still be years from running a “real” current account deficit.

When exactly the moment comes will also depend on how Beijing deals with the largest economic challenge it has faced since the crash of 2008: a trade war with the United States.

Stick or Twist

On the surface, you would expect a tariff war with China’s largest export market to push down the trade balance. As Setser explains, a reasonable first order estimate is that a 1% rise in import tariffs would normally reduce imports by 1%. If the trade war were to escalate further, this could have a real impact on China’s overall trade balance.

But things are unlikely to be so simple. First, the US’s demand for imports is rising due to the Trump administration’s tax cuts and the strong dollar. Second, the value of the RMB has experienced the sharpest downturn in decades since the trade war began to heat up in April. This will make China’s exports cheaper, partially offsetting the impact of US tariffs. It will also make imports and foreign trips more expensive for Chinese consumers.

The bigger issue, though, is whether the trade war causes Beijing to stall, or even rethink, its long-term plan to transition to a consumption-led economy. There are several reasons why Beijing may feel a return to the high-export, high-investment model is necessary, at least temporarily. One is simply to shore up growth, since the government appears to have little faith in consumption as a driver of the economy.

“A lot of Chinese growth when you look at GDP is generated by consumer spending, but the swings in economic activity appear to be still related to infrastructure investment,” explains Lubin of Citi. “There’s been a slowdown in 2018, and now the State Council has turned the taps back on.”

In August, there was a marked acceleration in the number of urban rail projects approved by the National Development and Reform Commission. The Ministry of Finance also ordered local governments to issue around RMB 1 trillion ($150 billion) worth of special bonds, used to finance infrastructure and new housing construction, within a two-month deadline.

Lubin also suspects that Beijing will be uneasy about running a current account deficit during a time of heightened tension with the US.

“The point about running a current account surplus for China is that it means they’re not dependent on foreign capital to finance their growth model, and so they have a high degree of autonomy,” says Lubin.

“The prospect of a current account deficit for China gives, in Beijing’s mind, the US some kind of strategic leverage over China.”

This is even more the case since any liabilities China would accumulate by running a deficit would likely be dollar-denominated. Beijing’s efforts to internationalize the RMB have taken a “substantial backward step” since 2015, Lubin notes.

But abandoning the transition to a consumption-led economy would be extremely costly for China, as Zhang of Fudan University emphasizes.

“It’s really hard to reverse course,” says Zhang. “That would mean lowering the costs of manufacturing production, lowering wage growth for workers and keeping the currency cheaper. It’s hard to imagine that China could do this after so many years and all the changes that have taken place.”

There are fundamental demographic pressures pushing up wages in China, and so the export-led model appears unsustainable in the long term. A signal that China was moving back in this direction would not only be unpopular politically but could also trigger a critical loss of investor confidence.

The central bank’s struggle to manage the exchange rate offers a sense of the dilemma facing China’s policymakers. While a depreciation may help China deal with the impact of the trade war, letting the rate fall too far could lead to panic in the financial markets.

“If the RMB rises to over seven against the dollar, I think that’s kind of an emotional threshold for investors,” says Zhang. In late July, the Politburo appeared to make keeping the rate under RMB 7 to the dollar official policy, proposing a “six stabilizations” approach.

There is also the question of how much China can continue to ramp up exports. “Global growth will not support Chinese export growth in the way that it has in the past, particularly if the US tries to close down Chinese export growth,” predicts Lubin. In this context, domestic demand may be the only sustainable driver of long-term growth.

Given these pressures, Beijing appears to be in a bind. To push forward with reforms in the current environment will be painful, but turning back will be even more so. Sooner or later, China will need to forge ahead, and this will move it inexorably toward a current account deficit.

Dealing with the Deficit

When China finally moves into a deficit, it will open up new risks, but also new opportunities. On the downside, the surplus has acted as a useful safety net for Beijing in the past. When the economy experienced capital flight in 2015 and 2016, China’s central bank drew on its enormous foreign exchange reserves to stabilize the market, spending around $1 trillion to prop up the exchange rate. If China is no longer able to use this kind of tool, the exchange rate will become more volatile.

A depletion of China’s forex reserves could also have implications for the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI). In his book on the BRI, China’s Asian Dream, Tom Miller explains that one of the reasons China launched the scheme was that it was looking for a more profitable investment channel for its large reserves. Offering commercial loans to finance foreign infrastructure projects had the potential to produce higher returns than US Treasurys. Now, some analysts argue that if the reserves start to dwindle, China may become less willing to throw money at high-risk projects.

Yet a current account deficit may help China increase its influence in other ways. For example, it could help China in its efforts finally to make the RMB a global currency. “If you want to export your money to the rest of the world, you have to import a large share of global production,” says Zhang. “You have to be a country with a large trade deficit.”

In many ways, Zhang argues, this could be a positive force, both for China and the global economy. “If China ran a trade deficit then it would contribute a lot more to global growth,” he says. “A trade deficit in the long run would not create a negative image of the Chinese economy. For large economies, a deficit has historically been a positive signal of an economy’s health.”

But to reap these benefits, China will need to complete its long-awaited transition to a new economic model. This journey is not going to be an easy one.

“The question of whether consumption continues to increase is largely a political one, and the answer depends on to what extent the government is able to reform the system to allow a transition away from investment policy,” says Maximilian Kärnfelt, an economic analyst at the Mercator Institute for China Studies (MERICS).

The most difficult obstacles still lie ahead, and Beijing will need to negotiate them without the safety harness of a bulging surplus.