What does the COVID-19 pandemic mean for China’s Belt and Road Initiative? The Belt and Road Initiative is one of the biggest development projects in history, but the pandemic has had a huge impact on the economies of the countries involved in it.

Pakistan has long been the jewel in the Belt and Road Initiative’s crown with China infrastructure projects under construction spanning some 3,000 kilometers and expected to cost more than $62 billion. Then came the pandemic.

Prime Minister Imran Khan vowed to complete the flagship project, known as the China Pakistan Economic Corridor (CPEC), “at all costs” but in April Islamabad appealed to Beijing for debt relief and to relax the terms on loans worth $30 billion.

Similar pleas have since echoed across the world, particularly from developing countries. To different extents, these countries have grown dependent on Chinese aid and loans and are just realizing the implications that the COVID-19 virus has added to their economies.

The foundations

The Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) was officially set in motion in 2013, with the vision of a seamless, transcontinental transport network—railways and roads, ports and pipelines—to connect Africa, Asia and Europe and bind the world in “mutual progress.” As the name suggests, there are two primary components: the Silk Road Economic Belt overland and the Maritime Silk Road at sea.

The former consists of six economic corridors linking Central Asia, Eastern and Western Europe with China through a snaking network of rail and road links. The latter involves a series of seaports marking the way from China to Africa, Europe and South-East Asia.

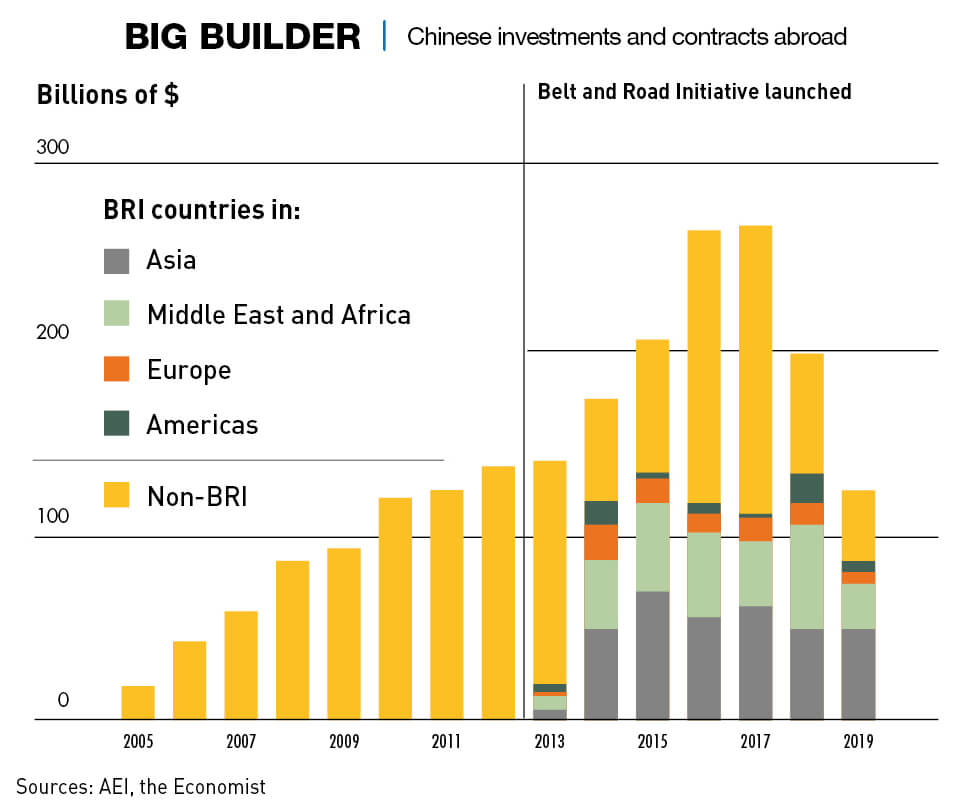

The BRI is made up of nearly 3,000 projects worldwide, racking up infrastructure costs so far worth a staggering $3.87 trillion, according to Refinitiv, a global provider of financial market data. The World Economic Forum estimates that $1.14 trillion worth of BRI projects will be completed by 2025.

Plugging a gap that other countries such as the United States missed, China was ready to finance the needs for big infrastructure upgrades, and in effect a revival of the ancient Silk Road linking China with the rest of the world. The loans used to fund most of the projects have come primarily from two sources: The Export-Import Bank of China and the China Development Bank. At the Belt and Road Forum in 2017, it was announced that both banks would designate an estimated $54 billion for BRI-related projects. Two years later, it seemed that both banks had already exhausted their credit lines.

Potential returns on projects are uncertain, but the debt implications for recipient countries are clear. According to the American think tank Council on Foreign Relations, as of 2017, Pakistan borrowed at least 7% of its GDP from China. Debts for Djibouti, Kyrgyzstan and Ethiopia totalled approximately 80%, 40% and 20% of their respective GDPs. All four countries have been identified as being highly vulnerable to debt distress. The Council’s BRI tracker found many other countries in a similar plight. COVID-19 has obviously complicated their situation.

The walls

Many nations buy into the promise of BRI as a catalyst for economic growth. In a survey conducted by Central Banking Publications, albeit pre-pandemic, 53% of the 30 participating central banks believe that BRI projects will boost their GDP by up to 1%. The remaining respondents think the yield will be even greater.

“Developing nations with either no means to finance their own projects or who are politically unwilling to accept the quid pro quo terms of Western or multilateral funding have found the initiative attractive,” says Kelsey Broderick, an Asia analyst at political risk consultancy Eurasia Group. “There was only one string [attached]: the use of Chinese components and firms to make the projects ‘bankable’ for China.”

“It has been beneficial for some less developing countries to host these projects,” says Yasiru Ranaraja, director at the Belt & Road Initiative Sri Lanka. “It helps them rebuild. In Sri Lanka, for example, there have been a lot of developments in the past 10 years thanks to BRI.”

The Southern Expressway, one notable example, was built with Chinese loans. This 222-kilometre-long (138 mi) highway linking the capital of Colombo with major towns in the south of the island and has allowed tourism and other industries to flourish.

Gwadar Port, situated in a small coastal city in southwest Pakistan, is another standout. The port’s potential has always been its strategic location at the intersection of oil and shipping lanes. Sure enough, it took center stage when CPEC was announced in 2015. Contracts worth $1.02 billion for port expansion were reportedly awarded, and the port was officially leased to China for 43 years, until 2059. China Overseas Port Holding Company, the port’s sole operator, envisaged it would help create 47,000 local jobs.

Yet as of 2018, only 99 ships have anchored at Gwadar Port. Critics say such underperformance calls into question the practicality of many BRI projects. But analysts such as Yue Su, China economist at The Economist Intelligence Unit, warn against rush judgements. “For such large-scale infrastructure projects, it can sometimes take 20 or 30 years to see a positive outcome. To measure their success and real impact, we need maybe another five years.”

The cracks

The trillion-dollar initiative is not without controversies. Criticism abounds about whether the BRI deals are in the best interests of recipient countries as the terms often lack transparency. Experts repeatedly cautioned against signing onto what some have called “debt-trap diplomacy.” But for many countries, there was no alternative sources of funding if they wanted to invest in specific infrastructure.

“Many are mired in a chicken-and-egg situation,” says Yihao Li, a PhD candidate in urban planning and development at Harvard University. “They don’t have money to develop their infrastructure, but the lack of it means they then cannot attract foreign investments. Securing loans too might be difficult as credit ratings for many of these countries are poor.”

Keshmeer Makun, an economics lecturer at Fiji’s University of the South Pacific, echoes this sentiment. “This lack in infrastructure investment, together with new risks like climate change, has been a huge barrier to economic progress. The introduction of BRI provided an alternative form of aid for many Pacific Island countries.”

Makun adds that funding under the initiative has also been more accessible relative to financing from other international agencies and players. “Long repayment plans and quick project completion timeframes were further draws.”

Another attraction: Many projects were not subject to the number or breadth of feasibility studies required by other lenders, says Broderick.

Also, what constitutes a BRI project is not so clear; many ongoing infrastructure investments by China have simply been rebranded under the initiative. “Take Hambantota Port in Sri Lanka, it was not designed for BRI,” says Ranaraja. “The port predates the initiative.”

Pandemic exposé

While hiccups were to be expected, a pandemic was low on the list of possibilities. The coronavirus outbreak has spared almost no one and the virus has wreaked havoc on many BRI projects. Virtually all projects were impacted as borders closed, while lockdowns brought economies to a standstill and disrupted global supply chains. China’s Ministry of Foreign Affairs estimated that almost all projects have been impacted with about one-fifth “seriously affected.”

Pakistan downsized its annual budget for CPEC by one-third—to $159 million from $241 million a year ago. Bangladesh shelved plans for a huge coal plant in Gazaria. Contract-signing for the Bangkok-Nakhon-Ratchasima high-speed rail link was postponed again, even though the coronavirus outbreak was not explicitly cited as the reason.

It comes as no surprise that low- and middle-income nations are struggling to deal with the economic fallout of the crisis. The truth is they were barely above the water before the coronavirus outbreak. In 2018, the Center for Global Development found that additional BRI-related loans could bring a “quite high” risk of debt distress for 23 of the 68 participating countries.

“The debt issue has been thrown into the spotlight again this year with COVID-19,” says Broderick, as countries have had to redirect limited funding and resources towards healthcare services instead. Many BRI loans were on the verge of default and debtors found themselves in an even more difficult repayment position than before.

The Asian Development Bank has predicted growth in most regional economies—where BRI projects are abundant—will slow, and many participating countries have asked for debt relief. One concern is that China may agree but with caveats that are hard to swallow. In 2017, Sri Lanka, unable to service an $8 billion loan, conceded control of 70% of its Hambantota Port to China on a 99-year lease.

Ready for redemption

In April, China announced it would suspend loan repayments for low-income countries until the end of the year. Several other announcements followed: during a virtual summit, President Xi said that interest-free loans to African nations due to be serviced this year would also be written off.

This also serves China’s interests by expanding its trade with huge developing markets just as its relationship with the developed world—particularly the US—is being thrown into question. “China needs to find other trading partners. Providing debt relief may help secure them,” says Yue. “BRI is also strategically significant, because China can use it as an economic tool to strengthen political ties with developing countries.”

China has the economic capabilities to support the strengthening of ties. The country’s second-quarter GDP growth was positive, and exports have started to climb again. “This means there is probably room to use its foreign reserves to lend to BRI countries,” adds Yue.

But precisely how much money would be re-allocated to BRI relief is not yet known. “The outward capital flow to the rest of the world has been very opaque,” says Li. “What we can expect, however, is more renegotiations and refinancing deals between BRI host countries and Chinese lenders.”

Another opportunity for China to capitalize on is the digital side of BRI. “It was already flourishing but it’s now supercharged due to the focus on healthcare,” says Ben Simpfendorder, founder and CEO of advisory firm Silk Road Associates. “Because the BRI region has a huge population, you can’t just go out and build hospitals across all cities. You need to find other solutions, and those solutions will be digital.”

He points to China’s Pearl River Delta, where exports have been growing faster than the rest of the country. “This is largely because the region is selling goods that are high in demand due to COVID-19—simple medical devices like hand-held temperature reading devices.”

The demand for other products, like thermal scanning systems and infrared temperature sensors, has similarly boomed. “There are huge opportunities for Chinese digital companies to provide such equipment and supporting technology to help strengthen the region’s health system.”

Making BRI the “project of the century” is a legacy President Xi keenly wants to leave behind. While the initiative is described as “an economic cooperation initiative … an open and inclusive process,” it is clear China needs to lead by example.

Buckle up

BRI looks likely to press ahead regardless of problems, including the body-blow from COVID-19. Beijing maintains that whatever impact the virus has on the initiative will only be “temporary.”

Whatever happens, the huge amount of money pumped into ambitious infrastructure projects so far will not have been for naught. And while the scale, nature and terms of agreements may be recalibrated, the game plan will remain the same. BRI will continue to pave new roads and new futures for economies.

“Such a mega initiative would be nothing without the leadership of China,” says Li. “And since the extent to which China is able to exercise that leadership depends highly on the domestic economy, BRI is likely here to stay.”

At the end of June, Beijing announced it had suspended debt repayments for 77 developing countries that have been sent reeling by the pandemic. While it is not yet clarified precisely to what extent Pakistan’s pleas for relief have been answered, overall, the Belt and Road Initiative will continue.

“The long-term impact is not yet clear,” says Broderick, “but it is likely that China will continue to promote and expand the initiative, including finding new areas of growth.”