A New Relationship

The UK-China relationship is one that has had its ups and downs over the centuries, and the last few years have seen something of a negative trend in relations between the two countries due to growing geopolitical tensions, Brexit and now the Ukraine war. Much needs to change in order for ties to be mended.

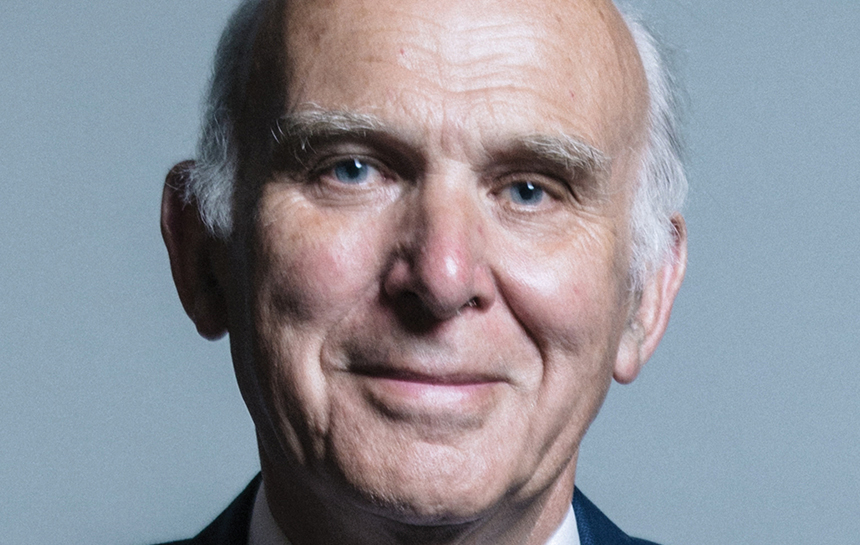

Sir Vince Cable, former UK Secretary of State for Business, Innovation and Skills, believes that there is hope for improving the relationship, but a lack of in-person contact due to COVID is hindering developments. In this interview he discusses these problems, alongside the effects of Brexit on the UK-China relationship, grassroots options for developing ties and the state of globalization overall.

Q. How would you characterize current UK-China economic relations and what are the key issues at work here?

A. I would characterize it as generally businesslike, across a wide front, but with increasing encroachment of geopolitical concerns. The Cold War philosophy has entered into certain areas that could be described as “strategic” or having some kind of quasi-security aspect. And we’re seeing that in more and more instances, including the announcement of the ban on the export of research technology from Manchester University. But apart from that, I think the relationship continues on a businesslike footing. I am conscious that we are in a fast-moving situation and my answers may well be different in a few months time. We have, for example, recently seen that Xi Jinping has consolidated his position as uncontested leader for the indefinite future; the disorderly collapse of the zero-COVID policy following remarkably widespread and outspoken public protests; and the intensification of American sanctions through a ban on the supply of sophisticated chips and the equipment to make them.

Q. To what degree has Brexit had an impact on UK-China relations, particularly economically?

A. I think it’s had a very profound impact, as it has on many aspects of British life. Specifically in relation to China, I think it’s had two consequences. First of all, from a Chinese point of view, I think it’s diminished Britain’s importance. I think the Chinese did see Britain as something of a gateway to the European Union, as an “in” for its investors and for negotiating on trade issues. And indeed, we had a sense 10 years ago that the Chinese prioritized Britain over Germany, even in terms of the European Union, because it was a point of access, and the attractions of doing business in London in the English language, and so on, were considerable. But now we’ve lost the idea of Britain as a gateway to the European Union.

I think the second thing, which will have an increasingly considerable effect, is that Britain has now drifted much more into the American sphere of influence. Looking at the world, Britain is now very firmly a transatlantic power rather than a European power, and Brexit has reinforced that. And the increasingly tense geopolitical relationship between the United States and China has affected the UK indirectly. Linked to that, Britain’s attempt, which you might think is rather strange, to position itself as an Asia-Pacific country has also become absorbed in this US-China competition. So I think in those two ways, it’s had a profound effect.

Q. There appears to be a general negative view of China in much of the world these days, whether that be governmental, business or public opinion. What are the reasons for this and what are the solutions?

A. I think that there is a considerable growth of negativity. Back in 2015, the conversation was around the so-called “golden era” in UK-China relations, although there were a few obvious points of difference. And that has profoundly changed since for several reasons. First of all, the whole geopolitical environment, the split between the Western democracies and their allies, and China has gathered momentum. The Ukraine war has further polarized relationships, with China being portrayed as being on the wrong side of that dispute. The fact that it has taken the same position as India, South Africa, Mexico and so on is largely overlooked. China is basically seen in Britain and the rest of the West as a Russian ally.

Secondly, there have been a whole lot of factors which have brought together right-wing and left-wing people in the UK, in terms of a more critical approach to China. One was Hong Kong, and the second is a mobilization of people around human rights issues.

Thirdly, COVID has had really quite damaging effects in reducing day-to-day contact, changing perceptions of China in a much more negative way. In terms of what can be done about it, it’s not obvious because these are quite deep-rooted problems. I would hope that we continue with businesslike relationships in terms of trade, investments and exchange of students. That’s the kind of thing that generally helps relationships to function well. But beyond that, I don’t have any magic solution.

Q. How is China’s position on the Ukraine war viewed in Britain and what are the potential economic consequences?

A. There is now a worry among companies who do business with China, that they may get caught up in a much more comprehensive sanctions regime. We’ve seen what happened when Russian foreign exchange reserves were impounded. At the moment, there is no suggestion that that kind of regime would be applied to China, but investors have at the back of their minds the fact that if relationships worsen or some military activity were to break out over Taiwan, they could be caught up in a sanctions regime such as the one that affects Russia currently. So I think the effect is kind of chilling on people wanting to do trade and investments in China.

Q. What opportunities do you see for British businesses in China and vice versa? And how can both governments facilitate greater involvement in each other’s market?

A. My impression is that companies that take a long-term view and are willing to incorporate a higher level of political risk, will continue to see opportunities in China. Because, after all, it is by some measures the biggest market and economy in the world. Indeed, many British companies have done well in China and they’ve developed good long-term relationships there. I don’t see why that shouldn’t continue. But of course, they and other companies will just factor in a higher level of political risk than existed before and will be inhibited by that.

Q. What can be done at a grassroots level, particularly in terms of company-to-company and people-to-people relationships, to keep China-UK relations on the right track?

A. Simply just having people going backwards and forwards again, like before. One of the things which has always struck me as being particularly attractive about China was that, whatever complaints people had about their political system, the simple point was that large numbers of Chinese traveled abroad every year as tourists, students and business people. There was a lot of interaction with Chinese people in universities, in commerce and elsewhere, and that kind of thing created good vibes, certainly on the Western side, and I hope with Chinese visitors, too. If we can build that kind of interaction at a personal level again, that cannot be anything but good.

I think linked to that is the issue of language. The point that many of us continue to make is that whereas many millions of Chinese are now developing an English capability, very few British people have any knowledge or understanding of Mandarin or the Chinese language. And the fact that it is such a very small number means that there is a barrier to communication. So in the long term, we should be trying to build up a number of Chinese speakers.

Q. To what extent have China’s COVID restrictions affected the ability of businesses from each market to operate in the other?

A. I think they have had a really bad effect, in both superficial and deeper ways. The fact that expatriates found it difficult to come and go, means it was very difficult to keep a close eye on their business, and operationally, it’s a major handicap. I think that there are also deeper issues here. First of all, it has increased this sense of isolation, and the perception of China being a remote place that we have nothing to do with, and I worry about that.

The second thing I think it has done is undermined the view that many of us has that China’s government was highly competent. I think the view of many Westerners was whether or not they agreed with the political system, they could at least say that it’s a very competent state. It’s efficient, builds good infrastructure and delivers competent, sensible economic policy. But the combination of vaccine nationalism and these totally disproportionate lockdown measures, has really undermined that.

Q. What are your thoughts on the state of globalization, given its historical importance to both the China and UK markets?

A. Globalization and international economic integration has been one of the dominant trends in our lifetime. And it has overwhelmingly been a force for good, not just in improving the living standards of Western societies, but helping China, India, and increasingly African countries to a higher standard of life, as a result of free trade and investment flows.

It’s now being questioned, from both the political right and the political left. However, I have to say that the statistics so far don’t suggest that much has changed. Whenever lockdown measures have been removed, trade has continued to flow freely and in growing volumes. But I fear that over time, the combined influence of the political consensus which is skeptical of globalization in the West, is going to take its toll. And I get a sense in China that there is a growing nationalist tendency, as opposed to a more liberal outward-looking tendency. And if the nationalistic feeling grows, then globalization will be undermined, but so far, it’s more rhetoric than actually having an impact on trade and investment.

Q. What are your thoughts on what some see as the decoupling of China from much of the rest of the world? How will this affect, among other things, the sharing of technology and research, and business relationships?

A. It’s bound to have a negative impact, and it’s happening on both sides. In the United States there is a growing emphasis on self-sufficiency in advanced technology, supply chains and chip development. And within China, we’ve had the dual circulation strategy for several years and growing emphasis on an industrial strategy which is based on self-reliance. This unpicking of interdependence is making the Western world and China less dependent on each other. You still have companies like Apple, which are heavily embedded in both the Western world and China, but that appears increasingly to be exceptional. I think that this decoupling process is largely negative in its impact and it will have a negative impact on China in particular.

Q. With a particular focus on business, how do you see the China-UK relationship developing over the next five to 10 years?

A. In the short run, there is room for considerable improvement, simply because of the end of the COVID pandemic. And if China does, in the next year or so, go back to normal in terms of fulfilling supply chain obligations, and Chinese students and tourists start traveling again, we will get a return to more of a sense of normalcy and welcome exchanges between our countries. So that will be positive. After that, I think it depends very much on how the geopolitical tensions resolve themselves. Given that there is a growing expectation of a military conflict around Taiwan, if these military alliances start to consolidate, things could get quite a bit worse. So I think the answer to your question is in the short run, we should see some improvement, once we get to the end of COVID. After that, it depends very much on how the geopolitical questions resolve themselves.

Interview by Patrick Body

Sir Vince Cable is the former UK Secretary of State for Business, Innovation and Skills, and the former leader of the Liberal Democrat Party. He also previously served as the Shadow Chancellor and is currently a visiting professor at the London School of Economics.