Chinese companies are buying up clubs and sports assets over the globe, but to what end?

Hosting a World Cup remains an elusive dream for Chinese football fans, but Chinese investors have managed to purchase some of the world’s best soccer clubs.

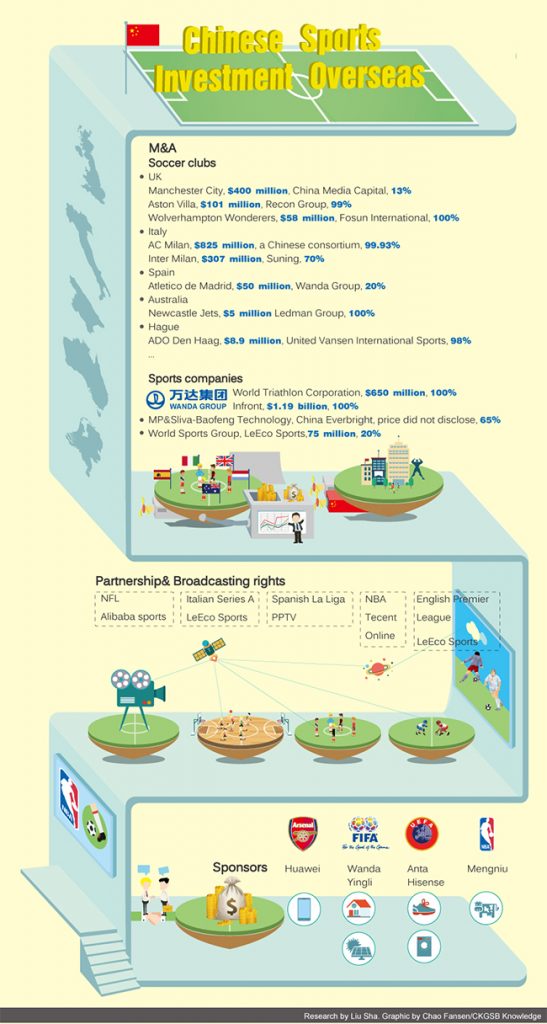

In early August, a Chinese company bought a 99.93% stake in Italian club AC Milan at a price of $825.8 million, two months after its rival Inter Milan was acquired by Chinese retail giant Suning.

The purchases have been coming thick and fast. Since 2015, Chinese companies have purchased 14 clubs including English stalwarts Manchester City and Aston Villa, Spanish club Atletico de Madrid and in Australia the Newcastle Jets.

Together the 14 club investments are valued at over $2 billion, demonstrating the strong Chinese interest in foreign sports assets. Aside from clubs, they’re also snapping up stakes in sports marketing companies and those with broadcasting and organization rights for tournaments.

There are many reasons behind these investments. Some investors think it’s a good opportunity to invest in the world-class sports assets when many of them are undervalued and cash-thirsty amid sluggish economic growth in Europe. As Gandini of Inter Milan put it: “in order to compete within this European scenario, you need to have big pockets.”

According to Fininvest, a private holding company owned by the family of Italian media tycoon and former President Silvio Berlusconi (the previous owner of AC Milan) the club has a debt of 220 million euros and the deal with the Chinese investor could lead to a “badly-needed” cash injection.

But for Chinese buyers, there are both political and economic factors at play.

In a country like China where economic development is closely related to government policies, it’s easy to envisage the political leverage these investments could potentially bring to buyers.

Chinese President Xi Jinping hasn’t hidden his love for football games or his disappointment with the national football team’s performance. He hopes that China could host a World Cup someday and that the Chinese team could qualify to attend and eventually win a World Cup.

Currently, China is ranked 78th worldwide.

Xi’s soccer hopes represent a chunk of the Chinese populace and commentariat who hope the sports market will develop and that sports can play a bigger role in boosting economic growth.

One goal in China’s 13th five-year plan, released in May 2016, specifies: the total scale of the sports industry should amount to over RMB 3 trillion by 2020 and it should comprise 1% of GDP, up from 0.6% now. This number in developed countries like the US is around 2%, says Yi Jiandong, a sports industry analyst with the National School of Development at Peking University.

With slowing GDP growth, China needs to go through economic restructuring and firms should seek opportunities in service and entertainment industries, Yi says.

And when domestic sports assets become unpredictable and prices go up, hot money will be invested offshore to mitigate risk, he adds.

Professor Simon Chadwick, the Chair in Sport Business Strategy and Marketing at Coventry University Business School, says that Chinese companies find it wise to be publicly seen supporting state policy.

“Buying a football club will not yield a significant direct return on investment. Although revenue streams in sports, particularly football, can be strong, the cost is a significant burden—most notably the player transfer fees and salary costs,” says Chadwick.

In fact, most club buyers were keen to tell the public that after buying those world-class clubs, there would be better chances for Chinese teams to learn and for young talent to be trained in Europe, thus helping Chinese football to improve.

These include Suning’s Chairman Zhang Jindong, who said, after announcing the Inter Milan acquisition, that Inter Milan’s talent academy would help young Chinese players. Dalian Wanda’s chairman Wang Jianlin, the richest man in China, after acquiring Atletico de Madrid, said the same thing: Chinese players will be able to be trained in European clubs.

And it’s more than clubs. When Wanda bought Swiss Sports Group Infront Sports & Media at a cost of $1.19 billion in 2015, Wang deemed the acquisition to be a move that could help China bid to host big sports events.

Wang said, while delivering a speech in January 2016, Wanda’s acquisition of Infront could help China host the Winter Olympics in 2022 because Infront has media agreements with seven events at the Winter Olympics including ice hockey, ice-skating and skiing.

He continued by saying that Wanda would focus on buying sports companies like Infront, which has broadcasting rights and media marketing rights, so that “China will have a bigger say on the international stage of sports.”

He also mentioned that he was given a front row seat at FIFA’s year-end meeting—“I was in the middle of the first row, the presidents of football associations in other continents all sat behind me. Infront is a major partner of FIFA. Had we not acquired Infront, we would not able to attend the FIFA meeting or receive their respect.”

Branding

Aside from political leverage, sizable returns on such investments will also come indirectly through the access overseas to new markets and business opportunities that investment in sports can facilitate, Chadwick adds.

Buying clubs and investing in top sporting brands can help boost other branding efforts, says Mark Pinner, Managing Director of Interel Consulting Group’s Beijing bureau.

He says that buying a club means buying the rights to produce branded products and many more market opportunities affiliated with the club.

“Branding through sports is a shortcut for Chinese companies to become known internationally,” said Ding Minghao, vice-president of Shankai Sports International, a leading sports marketing company in China, after white goods and electronics manufacturer Hisense allegedly spent 50 million euros to become a sponsor of the UEFA European Championship 2016.

Shankai Sports has helped Hisense broker this deal and worked together with it on UEFA’s related promotion campaign.

“Hisense saved five to eight years times in terms or popularization in overseas markets by branding itself at such a big sports events,” Ding says. Similar logic applies to clean energy company Yingli’s sponsorship of FIFA 2014: the company is targeting American and European markets.

Changing trend

“Currently most of the acquired sports assets are soccer clubs, which are relatively easier to buy because many good clubs are on sale,” says Feng Lin, CEO of Deal Globe, a London-based firm specializing in providing M&A related services in Europe.

“But buying clubs is not the best way to generate financial returns. The investors are aware of that, but many of them are doing it for strategic purposes and are using the clubs as leverage to enter the sports market,” he says.

“In the future, Chinese companies will be more interested in other properties: game organizations and media rights. Because no matter what deals they make, they want to connect with the Chinese market. But now many companies with no experience in the sports market can’t find these assets,” he adds.

For clubs, the ways to connect with Chinese market include talent training programs, player exchanges and expanding their Chinese fans.

One of the ways to make profit is to buy a second-tier club and sell it after elevating it to the first-tier camp. However, it can be even more difficult than it sounds.

After Fosun invested in the Wolverhampton Wanderers, a second-tier English club, Jeff Shi, the Fosun executive leading the deal, said they would take the Wolves back to the premier league, which houses the UK’s 20 best clubs. The last time the Wolves played in the Premier League was April 2012.

“Our reason for investing in the Wolves is very simple—we needed to find space for growth,” Shi said, adding the Wolves already have a good stadium, academy, young players and a good history. “The only thing we need to do is put money into the club for better players,” he told the Wolverhampton media Express & Star.

Tony Xia, who purchased Aston Villa, also made similar statement. However, Keith Wyness, the recently installed chief executive of Aston Villa, admits that getting into the Premier League is “without doubt one of the hardest football challenges,” the Financial Times recently reported.

The report also quoted Alexander Jarvis, owner of Blackbridge Cross Borders, a consultancy which has provided advice on several football deals involving Chinese investors, as saying that that many smaller Chinese companies appear to be acting on impulse even though they “have no experience of football” and “there’s a risk of the clubs and the Chinese investors getting duped.”

Aside from investing in clubs, another route has been to invest in sports marketing companies in order to get involved with tournaments.

As a pioneer in overseas investments, Wanda’s Wang Jianlin told Reuters that Wanda would prefer to invest in profitable sports events rather than money-losing clubs.

This is because working with sports bodies rather than clubs can generate more innovative means of connecting with the Chinese market, says Feng.

Recently, the World Triathlon Corporation (WTC) started an Ironman training camp in Beijing. Wanda is the financial backer behind the scenes, having spent $650 million acquiring the WTC, which owns the “Ironman” franchise.

Wang has indicated that as a “the world’s toughest race” triathlons could become a popular game in China.

The company is going all out—holding reality shows, organizing more races, setting up training camps—across Chinese cities to promote the game. “Wanda’s goal is to increase the number of amateur triathletes to 200,000 in China, up from the current 100,” Wang said.

It’s hard to say whether the likes of Wanda will become gatekeepers of the Chinese sports market, but they will establish a strategic “first mover” advantage, says Chadwick. “What will be crucial for these businesses though, is their ability to protect this position through, for example, product innovation, mergers and acquisitions,” he adds.

Building partnerships with tournaments and sports companies is another way.

Alisports, a sports arm under the e-commerce giant Alibaba, has signed a partnership with The National Football League, a professional American football league in North America. It has also inked an agreement with the International Boxing Association. Similar to Wanda’s approach to the Ironman events, Alisports sees a chance to promote and popularize American football and boxing and building on their already existing footprint in the Chinese market.

Tencent has bought the exclusive broadcasting rights of the National Basketball Association (NBA) in China and thus has become the only company that can run a NBA Chinese website. Given the sport’s massive popularity in China, this allowed it to quickly generate a cash flow. It also works with sports media giant ESPN, localizing ESPN’s content on Tencent’s digital platform. According to ESPN, the two sides have reached an agreement which states that they will combine “Tencent’s vast user base across the globe and ESPN’s expertise in sports content creation.”

“Tech companies have large amounts of users and so they’re good at distributing content and matching audiences to games,” says Feng.

As the buying spree goes on and the market keeps growing, it’s worth mentioning there won’t be only Chinese players. “Foreign entrepreneurs are also eyeing the Chinese market and so when they’re selling, they would not sell 100% of the company or the club,” says Feng.

Feng’s company Deal Globe has helped China tech company Baofeng to acquire 65% equity in MP&Silva. “The reason they held 35% is because they have high expectations in the Chinese market and hope to exploit it with its Chinese partner.”

Impact on domestic sports industry?

Despite the promises Chinese CEOs have made to train young Chinese talent at top soccer clubs, Zhang Daqi, a freelance football coach based in Beijing, says it will take a long time before young Chinese players to benefit from the acquisition of those clubs. “Most of the club players are busy with different games and their owners or investors will spend money signing more expensive players, while training young talent is hardly a priority. And for some clubs in which Chinese companies only have a small stake, it’s not easy to get their players to come to China to coach the young players,” Zhang adds.

Zhong Qi, an analyst with Haitong Securities, says that with so much capital flowing though the market, Chinese consumer demand will be prompted with reliable supply. This will consist of access to different kinds of games, sports-related products and innovative ways to watch and participate in the games. There will be more tournaments and more people participating in mass sports activities. Zhong thinks that once there is growing demand, there is a greater chance for the industry to prosper.

“Overseas investments can be a catalyzer for the Chinese sports market, but whether it could help the national team’s performance or help to train better players remains unknown,” says Zhang.

Risk control

Loletta Chow, Global Leader of EY China Overseas Investment Work, says that Chinese companies’ strategic investments overseas will expand the domestic market and optimize the sports industrial chain.

But, as many investments are in Europe, there are some risks caused by the uncertainties of European society, says Chow.

The external risks have three origins, says Chow. “First, Brexit might increase the risk of other countries leaving the European Union; second, the continuous refugees flowing in will add pressure on the public funds of some governments, and third, potential terrorist attacks”.

When making an investment budget and the assumed return on assets, all those factors should be taken into consideration and after making an investment decision, a company should buy insurance to evade risk, says Chow.

Chow adds that companies should also know local country’s law and tax regulations and conduct specific research, like how much influence the increasing numbers of refugees will have on the labor market.Trend