Economic changes and government policies are driving millions of China’s migrant workers away from the wealthy coastal regions. What impact will the exodus have?

In late November, shocking images from the outskirts of Beijing spread like wildfire across China’s social media, showing streets strewn with rubble, shivering people hunched over in the freezing cold, piles of hastily-packed bags lying among the detritus.

The chaos was caused by a “clean-up” campaign launched by the Beijing government following a fire the previous week in a workers’ dormitory, which killed at least 19 people. Officials said the mass evictions were necessary to root out unsafe and illegal housing.

Whatever the intentions of the campaign, the incident served as a stark reminder of the increasingly uncertain future facing China’s 280 million migrant workers in a rapidly-changing world.

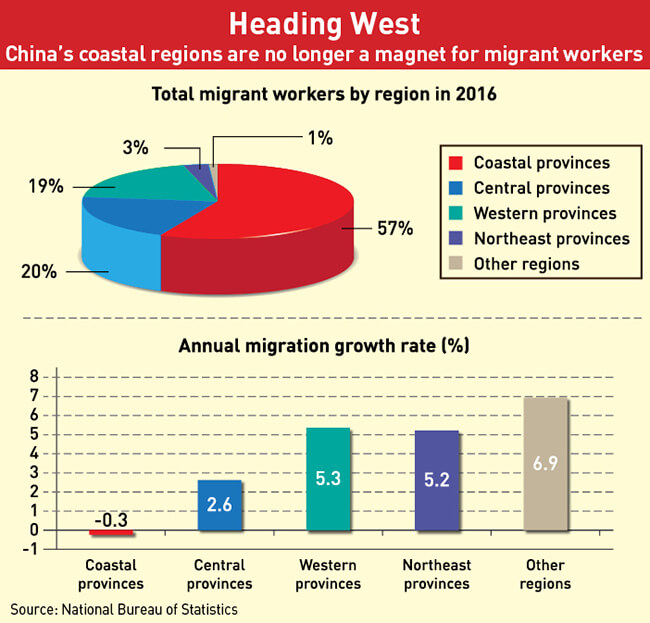

For the past 30 years, China’s economic miracle has been largely fueled by the movement of people into the coastal cities. But in the past couple of years, this trend has begun to reverse itself. The migrant workforce in China’s coastal provinces shrank by 0.3% in 2016, while the number of migrants working in the less developed western provinces rose 5.3%, according to a National Bureau of Statistics survey.

“A lot of people are returning to their homes, especially from Beijing,” says Xu Bing, a business owner from Chashui, a village in Anhui Province. “A lot of factories are… closing and there’s nowhere else to go, so they come back.”

Like the earlier outward-bound flood from west to east, this new wave of migration is being driven largely by the government. People are being encouraged to go “home” using a range of policy carrots and, as events in Beijing indicated, a few sticks. The question is what impact this trend will have on those heading west and on the Chinese economy.

End of an Era

The trend toward westward migration is a clear sign that a fundamental change to China’s economy is in progress, as a growth model that lifted more than half a billion people out of poverty starts to slow.

From the early 1990s onwards, China’s double-digit GDP growth was fueled largely by the cheap labor provided by people leaving their farms in China’s poorer inland provinces to find work in the factories springing up along the coast.

“The general estimate is 20% of economic growth in China was directly accredited to taking people out of the countryside and putting them in cities,” says Bradley Gardner, author of China’s Great Migration, adding that the 20% figure is a conservative estimate because it does not account for the indirect benefits of migration such as the creation of industrial clusters in cities like Dongguan and Shenzhen.

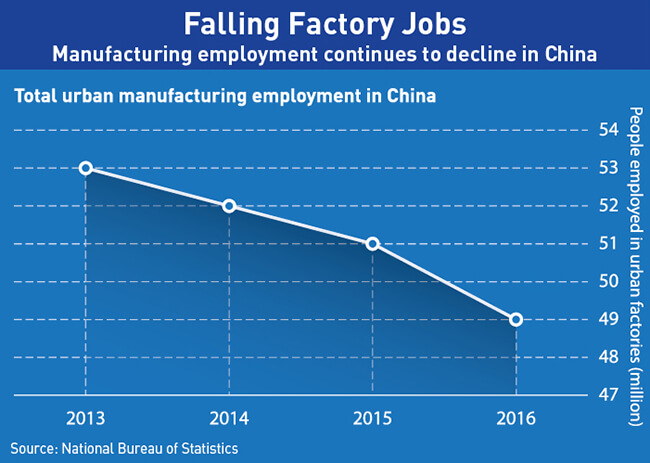

But the “made in China” model of rapid growth based on cheap, labor-intensive manufacturing already appears to be on the wane. In 2008, 37.2% of Chinese migrant workers worked in factories. By 2016, the figure had dropped to 30.5%, as services overtook manufacturing as the biggest employer of migrant labor.

The decline in manufacturing jobs is being driven by several factors, including rising wages. The average salary of a Chinese factory worker rose 64% between 2011 and 2016 to reach $3.60 per hour, according to market researchers Euromonitor. This is making life tough for factories in low-margin industries.

Xu Bing has noticed a rise in the number of people being laid off from factories. “More are coming back from jobs in export-oriented factories, clothing and products like that,” he says. “Costs are now too high for the factories so they’re closing. A lot of privately-owned companies have just closed down.”

Manufacturers are also being affected by China’s crackdown on pollution, which has ramped up significantly since 2014. “A lot of factories are being closed due to the environmental regulations,” notes Xu.

China’s government is accelerating this trend by encouraging manufacturers to automate production. “[Automation] is not just a corporate behavior; in China, it is definitely a Chinese government decision as well,” says Jenny Chan, Assistant Professor at Hong Kong Polytechnic University.

Many local governments are providing subsidies to factories to help them purchase industrial robots, raising the prospect of massive layoffs. In Zhejiang Province, robots replaced more than 2 million workers between 2013 and 2015, Chan points out.

Logistical Problems

The services sector has so far done a good job of creating new jobs to offset the layoffs in manufacturing, and China’s official unemployment rate actually dropped to 4.0% in 2016, according to the NBS (although these figures do not include migrant workers).

Migrants can find new jobs in a different industry without having to move back to their hometowns, and many have done just that. When Chan spent time investigating working conditions for migrants in Beijing, she found many people had moved directly from factories to working as drivers for logistics and e-commerce companies such as Yinda, SF Express and JD.com, delivering everything from packages to pizzas. “Some of them, to my surprise, actually had been working for Foxconn in Taiyuan,” she recalls.

Tens of millions of people are now working in China’s delivery industry, attracted by the potentially higher salaries on offer. Chan says some workers she met earned more than RMB 8,000 ($1,200) per month, more than double what most would earn in a factory.

But the work is exhausting and more precarious than factory work since delivery workers are typically classified as independent contractors, meaning that they have no entitlement to benefits such as sick pay or insurance and can be fired at a moment’s notice.

What’s more, the living conditions of delivery workers usually compare badly with those of factory workers. “It’s often even worse than what I saw as an undercover researcher at Foxconn,” says Chan. “Foxconn is bad, but it’s still an 18-storey, highly modern dormitory. But at the Yinda workplace, it’s really just a makeshift place.” The November fire provided a sobering example of the dangers posed by ramshackle living spaces.

Go West

It is not only delivery drivers finding life tough in China’s big cities. Rising living costs and other pressures are leading more people to consider trying their luck elsewhere. Yuan Jiasheng, a teacher who moved to Shanghai from nearby Jiangsu province, said she had considered moving back to her hometown. “There are more problems in big cities,” she says. “A good job in a small city is better than a common job in a big city.”

Chan echoes this comment. “The push factors [are also important]. It has become overcrowded and unfriendly and polluted in the cities,” she says.

In the past, the higher salaries on offer on the coast outweighed any concerns about these issues for most migrants. But Chan has observed that for an increasing number of people, earning the highest wage possible is no longer the only priority. Instead, they are focusing on access to public services like health care, pensions and social security.

“That really tells you that they are hoping to get a secure life in the long run,” says Chan. “In the past they didn’t care so much about social insurance, they would love to get more wages instead of looking into the long term.”

For migrant workers, attaining this long-term security largely depends on becoming an official resident in their new city under China’s hukou, or household registration system.

Those who live in a city but do not have hukou face a number of challenges in accessing public services as Guan Hao, a sales manager from Shanxi Province who lives in Shanghai, has found. He is relatively fortunate as his company provides him with social insurance, but his lack of hukou makes it almost impossible to own a car, buy a house or, in the future, send his children to public school. Those on lower incomes are affected even more severely.

Many migrants moved to the coasts in the expectation that the hukou system would eventually be abolished, but this has not happened and there is no sign it will. In fact, in Beijing and Shanghai the restrictions have got tighter still as the cities try to cap their populations at 23 million and 25 million, respectively. Even for graduates like Guan, attaining a hukou in Shanghai seems an impossible dream. “It’s like a joke. People want the hukou, so they go to the Shanghai government to apply, and the government says, ‘OK, but you have to wait 15 years,’” he says.

Instead, the government is encouraging people to move inland to spur economic development in the lower-income regions and ease the pressure on the big cities’ overstretched infrastructure. One of the ways it is doing this is by offering migrants hukou status in these smaller cities. “The hukou system in those small- and medium-sized cities is almost freed, fully reformed, to accept more people in the urban area,” says Lu Ming, Professor at Shanghai Jiao Tong University.

The government is also investing billions in these regions in a bid to attract migrants and stimulate growth. Massive subsidies have helped turn unfashionable Guiyang in southwest China into a big data hub, with Apple, Qualcomm, Microsoft and Tencent all setting up facilities there, while Foxconn was lured to build its “iPhone City” hub in Zhengzhou in central Henan Province. “Investment is rising very fast in those inland regions,” says Lu.

For increasing numbers of migrant workers, the choice appears quite simple, Lu explains. “On the one hand, in the coastal areas where they receive more migrants, relatively speaking they are discriminating against migration even more than before. At the same time, in your hometown nearby, you can find better jobs [than before]. Why not stay?”

Rebalancing Challenges

Many migrant workers appear to be making the same calculation. In 2016, 88% of the rise in migration came from people moving to a city within their home province, rather than to another province, according to the NBS. Chan expects that unless there is a change in policy, this trend will continue. “I still see the trend of migrating out of the hometown or villages [continuing], but it might be closer to home,” she says.

The return of large numbers of people has been beneficial for many parts of the Chinese hinterland. “In the rural areas, the economy seems pretty good,” observes Anhui business owner Xu. “With labor coming back to the rural areas, it definitely has a positive impact on local development. In the past, when they came back once a year bringing a bit of money with them, that was no use.”

“In places like Zhengzhou… it’s worked out very well,” agrees Gardner. “Migrant workers have flooded into these areas because the price of housing is really low… and they’re closer to their families.”

The influx of people has also helped alleviate a potentially alarming property glut in many inland cities. “Part of the reason why they’ve had this investment … was that there was fantastic overbuilding of housing in those areas,” Gardner explains.

But the government’s rebalancing strategy also has fundamental problems, not least that it essentially runs counter to market logic. “They’re trying to redirect migrant workers away from places where they can make more money to places where they can make less money,” says Gardner.

In some cases, the western development projects pay off, but there are also costly mistakes. “Sometimes the government invests a lot of money, and seizes a lot of land, and migrants never show up,” Gardner told The Diplomat in a July interview.

What’s more, the policy methods the government is using to cajole migrants and investors to move inland have had significant side effects. One example is the huge rises in land and property prices in the big cities, which has in large part been caused by the government’s decision to restrict land supply in an effort to reduce migration. “In China, we restrict land supply and accordingly we also restrict housing supply as a policy to restrict population growth. This is distortion,” argues Lu.

This has not only made life tough for people in the cities, particularly migrants forced to live in appalling conditions; it has also accelerated the decline of the manufacturing sector, as rising land prices increase costs for factories. “Those policies have raised the costs in the coastal areas too early, too fast,” Lu adds.

The hukou restrictions have also had a terrible impact on the well-being of migrants’ children. Those who move with their families to the city often have their education disrupted, while many of the estimated 60 million children who are left behind by their parents in the countryside suffer lasting emotional trauma. According to one study by Guangzhou University, nearly 80% of young migrant workers with criminal records were once left-behind children. “In the short term, it’s a social problem. But in the long run, it’s an economic and even a political issue,” predicts Lu.

Reversing the Flow

For many analysts, the problem with China’s economy is not that its major cities are too big; it’s that they are not big enough. “If you compare the urbanization ratio with other countries at the same development level… China’s urbanization ratio is at least 10% lower at this point,” says Lu.

Trying to restrict the growth of the country’s top cities is counterproductive as a policy for reducing poverty in the long run, Lu argues, because big cities generate more wealth, create more jobs and raise income levels faster than smaller cities. At the moment, “people and economic activities are not located in the places where they can have higher returns,” he says.

Gardner seconds this point. “[The rebalancing] might take some burden off Shanghai’s infrastructure,” he says. “But in terms of the overall amount of economic growth that we’re going to be seeing, it’s not great.”

The current strains on infrastructure and public services in Beijing and Shanghai are mainly due to poor planning, according to Lu. “The current supply… is actually based on a prediction of population [made] in the late-1990s,” he states, adding that Shanghai expected to have 18 million people in 2020, but already has more than 24 million.

The obvious solution to these issues is for the government to allow the big cities to grow. In the aftermath of the “clean-up” campaign, this seems further away than ever. But there are tentative signs that a change may be coming.

“The issue is whether Shanghai and Beijing should also open their hukou systems and whether [their] land supply should also be increased,” says Lu. “What I can see is, they’re actually doing so, but they’re not saying so.”

Lu believes a number of recent moves by the government indicate that it is becoming more open to a market-led migration policy. Beijing recently announced dramatic rises in the amount of land being made available for affordable housing, and more officials are saying that “land supply should be consistent with migration direction, not against it.” Meanwhile, the appointment of Xi Jinping ally Li Qiang as party chief of Shanghai could be a sign that the central government is ready to push forward the creation of a megacity encompassing Shanghai and other cities in Zhejiang and Jiangsu provinces.

Does this mean that the recent trend toward inland migration could soon reverse itself? “The answer to your question depends on whether you believe that China will continue implementing the current policy or they will really move to a market economy,” says Lu. “If you believe the latter, I can say with confidence that they will move to the places where they can find better jobs.”