China’s new data regulations pose challenges for business, but they also provide an increased level of data security for the country and its citizens

Data security and data sovereignty are becoming increasingly important factors in global governance

Didi Chuxing’s $4.4 billion IPO on the New York Stock Exchange (NYSE) went south fast. Within days of the June 2021 listing, the Cybersecurity Administration of China (CAC) launched an investigation into the company and banned new downloads of its app from local app stores. Its share price plummeted. By December, regulators ordered Didi to delist from the NYSE.

Like other governments around the world, the Chinese government is paying ever greater attention to data security, the process of protecting data from unauthorized access and data corruption throughout its lifecycle, and privacy concerns and is placing ever greater restrictions on companies with regard to the data they collect via their business. And Didi’s information was particularly broad and sensitive in its nature because it has information on where just about everybody is going in China, all of the time.

“‘Data security’ is a good way for regulators and other government stakeholders to package what transpired with Didi Chuxing,” says Ross Darrell Feingold, senior advisor at DC International Advisory, a global political risk consultancy.

Didi’s travails are not only its own; they are representative of the problems of a sector which has long seen data as a golden egg. It and other tech giants rely on insights they glean from user data to customize products and services for customers, but for years, the collection and use of this data went largely unchecked. “Having control of data is so important today because people’s daily activities are highly dependent on digital tools,” says Lee Cheng-hwa, an industry analyst at the Market Intelligence & Consulting Institute. “Their digital trajectory becomes the key to quickly understanding, identifying and monetizing consumer preferences.”

Yet with the regulatory winds changing, the country’s tech giants face choppy waters ahead. In March 2021 during a meeting of China’s top financial supervisory committee, Chinese leader Xi Jinping ordered regulators to tighten oversight of internet companies and crack down on monopolies.

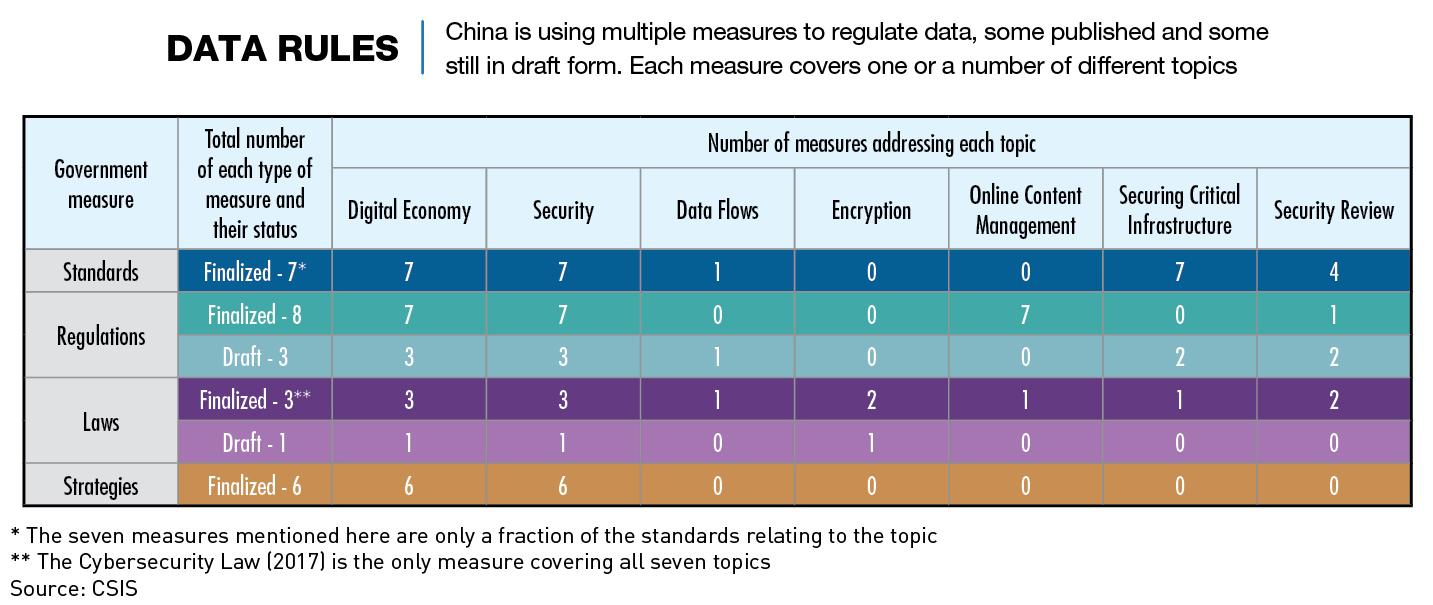

Since then, Beijing has moved steadily to create a policy framework that requires full oversight of user data held by private sector companies—primarily China’s own tech giants. In late 2021, both the Data Security Law and the Personal Information Protection Law came into force. Together with 2017’s Cybersecurity Law, they give the state a stronger role in the protection of user data and also greater oversight of the potential flow of China data beyond the country’s borders.

Chinese tech firms that once may have sought to list in New York will now have to think twice. The operations of multinational firms in China are also being affected, and in order to comply with the regulations they have all set up local data storage operations.

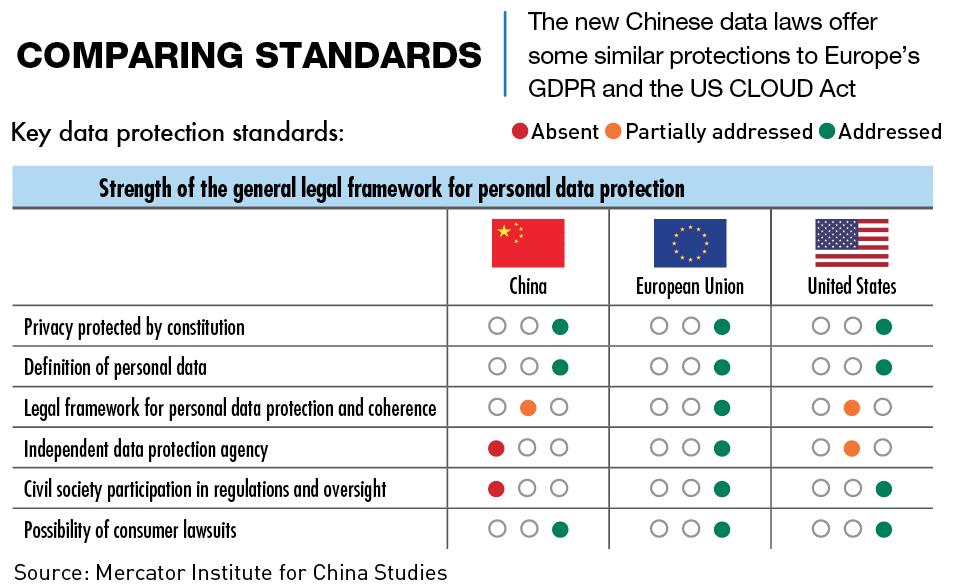

China’s new regulatory controls over data are not unique and also not necessarily more stringent than other jurisdictions in the West. Similar new data regulations have been promulgated in the United States and Europe, in Washington’s case the Clarifying Lawful Overseas Use of Data Act (CLOUD Act) and Brussels’ General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR).

And while the regulations will certainly lead to changes in the way that companies operate, the recognition by both the state and private enterprise of the value of data, especially over the past five years, has resulted in high levels of innovation and technological development.

“The Chinese government considers data an indispensable asset and resource for driving AI-based algorithms, and asserting economic strength and national power in an increasingly digital world,” says Daniel Tu, founder and managing director of Hong Kong-based Active Creation Capital and former chief innovation officer of Ping An Group.

Given the importance of data to innovation and development, the firms which come out on top will be those that are best able to adapt to China’s fast-changing data regulations. “For China’s technology firms, the era of free data collection and usage in China [in terms of consent, liability and cost], is over,” says Winston Ma, author of The Digital War: How China’s Tech Power Shapes the Future of AI, Blockchain and Cyberspace.

Evolving regulations

The first draft of the Personal Information Protection Law (PIPL) came into effect in November 2021. It laid out for the first time, a comprehensive set of rules governing data collection and protection in China’s digital economy. Previously, various pieces of legislation governing data such as the 2019 E-commerce Law and new Civil Code, introduced in January 2021, “covered data protection in a piecemeal fashion,” says Ma. “Together with the new Data Security Law and Civil Code, China has developed a complete data regulation framework to cover the complex relationships between individual users, tech corporations and the government,” he adds.

The Data Security Law (DSL) is the country’s first law designed to limit the ways companies can process and use data, says Active Creation Capital’s Tu. The law lays down the rules for the use, resale and movement of data, including across borders. The law also prevents companies from providing any data stored in China, regardless of sensitivity or whether it was initially collected in the country, to any foreign judicial or law enforcement agency without first gaining prior approval from the relevant Chinese authorities. Fines for violating the law can reach RMB 10 million and violators may also face potential criminal liability.

“Equally important is that the DSL expands the scope of regulation to cover not just the initial collectors of data, but also downstream “intermediary services” that use data for commercial and marketing purposes,” Tu says. “These downstream data handlers are required to ask their data providers to explain their data sources.”

As for the PIPL, like the EU’s GDPR, it lays out a set of consumer privacy rights in three categories: informative, corrective and restrictive. These rights allow individuals to receive a copy of their data, to correct or delete it if necessary, and to control its use—such as in decision-making that relies on AI technology. “For example, a bank would have to demonstrate it can reach the same result through a manual process rather than just running the request through an AI decision engine,” Nader Henein, privacy research VP at Gartner, said in a November 2021 Fortune commentary.

However, the EU GDPR also differs from China’s data laws in important ways. “The former is focused on protecting EU residents’ personal information collected by individual enterprises,” says MIC’s Lee. In contrast, China’s data laws are more expansive in their coverage, while penalties for violating them go beyond monetary fines. “For China, it is all about national security,” he says.

Under the PIPL, “there are very serious administrative and criminal punishments for the violators who intentionally or unintentionally process personal information in breach of China’s national security requirement,” China-based lawyers Ken Dai and Jet Deng said in an article comparing the GDPR and PIPL.

A key message Beijing intends to convey with its new data legislation is that “cyberspace is not beyond the law,” says Tom Nunlist, a senior tech and data policy analyst at research firm Trivium China.

Yet security issues are not Beijing’s sole consideration. “It’s 50/50, security and economics. It’s about keeping these two things in balance with each other, and fostering data as a national resource: recognizing it, protecting it and facilitating its use,” he adds.

To that end, China’s tightening data oversight also can be seen as a response to consumer needs. “After years of Chinese internet companies building business models around Chinese people’s lack of awareness about privacy, users are becoming more knowledgeable, and they are becoming angry with companies abusing their personal information,” says Winston Ma.

Compliance burden

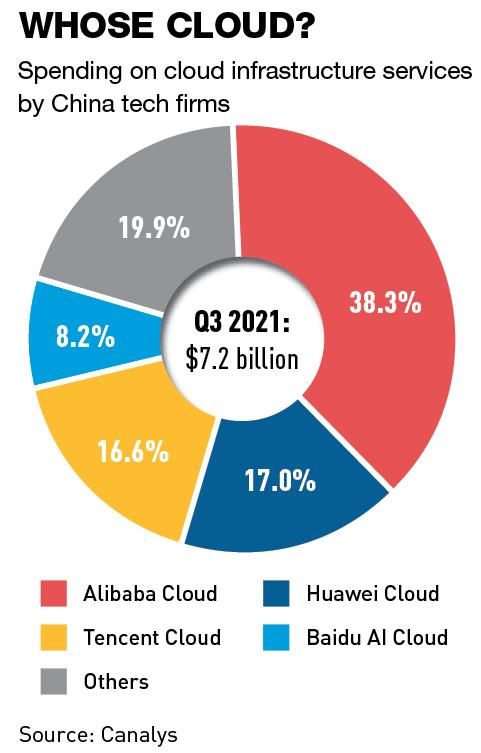

China’s tightening data regulations affect both domestic and multinational firms, with local tech giants likely to take the biggest hit in the short run. For instance, in the 12 months after the nixing of the IPO planned by Ant Financial, a major fintech company controlled by Jack Ma, the market capitalization of Alibaba, which is also controlled by Ma, fell more than 50%. Investors are reacting to the company’s regulatory travails, including an obligatory restructuring. It will have to relinquish some control over consumer data that has been integral to its competitive advantage in digital financial services, likely by setting up a personal credit reporting company.

Big platform companies are being singled out by regulators because “they collect personal information on a massive scale,” says Trivium’s Nunlist. Compared to companies without such vast troves of user data, “they get the scrutiny from regulators. The compliance burden is pretty significant.”

The new regulatory framework likely means changes are in store for how China’s internet giants operate. “Companies like Alibaba, Tencent and ByteDance will have to rethink their business models and how they collect data,” says Winston Ma.

Multinationals operating in China, meanwhile, face a different set of challenges. Cross-border data transfer will get more complicated for them. In the PIPL’s case, there is a requirement for individual user consent for data to be transferred out of China. “Consent makes cross-border transfers impractical, because even if a minority of individuals object to the transfer of their data, it would require the establishment of local store-and-compute capabilities,” Gartner’s Henein noted in the Fortune commentary.

Some multinationals with large China businesses chose to develop greater local data storage capabilities ahead of the two new laws. State-owned Guizhou Cloud took over as operator of Apple’s Chinese iCloud service in 2018 while the US tech giant launched its first China data center in Guizhou Province last May. Apple also plans to establish a data center in Inner Mongolia. That same month, electric carmaker Tesla said it had established a data center in China for the purposes of “localization of data storage” and that it would add more domestic data storage facilities in the future. China is Tesla’s second-largest market after the US.

One area to watch is what the new laws mean for multinational companies in terms of complying with foreign government sanctions. This is especially important given the increased frequency with which other governments are placing sanctions on various Chinese entities, even if they do not necessarily have assets outside China, says political risk analyst Feingold. “Multinational companies might have some challenging data requests from foreign governments to deal with.”

Data as the new oil

In 2013, shortly after beginning his first term, Chinese leader Xi Jinping said, “The vast ocean of data, just like oil resources during industrialization, contains immense productive power and opportunities. Whoever controls Big Data technologies will control the resources for development and have the upper hand.”

Broadly speaking, Xi was underscoring the importance of China as a country taking a leading role in the cultivation of Big Data technologies. The 13th Five-Year Plan vowed “to implement the national big data strategy” while at the 19th National Congress in 2017 Xi emphasized the need to “promote the deepened integration of Internet, Big Data and artificial intelligence with the real economy.”

The trifecta of legislation that has accompanied these broad policy objectives—the Cybersecurity Law, Data Security Law and Personal Information Protection Law—has been aimed at cementing China’s data governance model. “The overarching motivation is exercising cyber sovereignty,” says Active Creation Capital’s Tu. “Beijing also regards data and the digital economy as a major opportunity to overtake the US and the West.”

Winston Ma notes that China is the largest data market in the world. And he expects that China will continue to develop its data rules to cover more aspects of the new digital economy. “China’s data rules will become an important reference case for the world, especially the emerging markets, as more and more countries are starting to develop their own data regulations,” he says.

One risk for China is that the state’s increasing attempts to control data use and flows in the private sector could blunt the edge of its top internet companies. While there is broad consensus that more comprehensive regulation of their data practices is needed, there are some concerns that regulators may go too far.

However, Herbert Yum, a research manager at Euromonitor International in Hong Kong, expects that China’s tech giants will be hardy enough to withstand the changes. “Since they are not fixed-asset intensive, they are more resilient [than firms which are] to adverse events in the economic cycle,” he says.

In some respects, the new regulations appear to put multinationals at a disadvantage vis-à-vis local firms. “Some of these measures have a protectionist result, because in the space of the largest data collectors, Chinese companies will have a better ability to quickly implement (at least in the short term) sufficient compliance measures,” political risk analyst Feingold says. He expects that all multinationals need to reconsider their China mainland operations in light of the new rules, obtain outside legal advice, possibly procure new information technology hardware and software, and enhance firewalls to ring-fence China’s data. Such measures may require internal approval at the regional or global level.

At the same time, larger multinationals tend to already have in place governance structures that see company-wide adherence to the strictest set of regulations of any jurisdiction they operate in. So for many companies, the China rules are merely requiring the same level of data compliance they already have in place.

Whatever the case, multinationals will have little choice but to comply with the tougher data laws. “In the near future, the business environment [in China] will be less and less free, but the market remains a huge opportunity,” says Euromonitor’s Yum. “So, businesses that don’t want to give up this market will need to learn how to operate safely there.”