The government is putting wealth management in China under the microscope, and is slowly catching up with the inherent risk of wealth management products. Can banks continue to invent new skirting methods?

Bank deposits are boring, says Jane, a new recruit at a local bank in Shanghai. In a country where the government holds deposit rates artificially low, sometimes dipping below inflation, people are eager to shed the title ‘depositor’ for a more aggressive appellation—say, ‘investor’. Bankers are just as weary, if not anxious.

Since 2009, China’s biggest commercial banks have pieced together a universe of high-yielding investment options, known as wealth management products or WMPs. Compared to a bank deposit that might yield a paltry 0.8% after accounting for inflation, an annualized 5% or higher return from WMPs is attractive. As the country slowly liberalizes the interest rate on deposits, the banks are faced with mounting pressure to maintain high rates of profitability. That’s already proving difficult with the advent of internet banking, which dodges central rules to compete for depositors’ cash. Margins will begin to slip when the big banks have to start competing on interest rates. In the face of these challenges, WMPs are helping the banks make more money with their money.

And depositors have hungrily swallowed the products up, often emptying their deposit accounts to meet the products’ minimum required investment. “Everyone these days buys some kind of wealth product. It’s basic now,” says Jane, who has asked to go by a pseudonym because she Isn’t authorized to speak with the press.

Not everyone is as excited with the burgeoning WMP market, however. China’s financial regulators, particularly the banking regulator, have been uneasy about the rapid rise of these markedly opaque investment products. WMPs mature quickly, often too fast to produce the promised rate of return, some analysts fear. Not only do the investors not know the ultimate destination of their money—perhaps a risky real estate venture or a coal mine in need of debt refinancing— many also consider WMPs guaranteed by the banks in the same way as deposits. Most aren’t.

Regulators have been chipping away at the wealth management market since 2010, but the past year has witnessed a determined attempt to rein in exponential growth, fearing the products pose a systemic risk to China’s financial system.

Still, industry insiders say banks continue to ramp up WMP sales. “There isn’t such a noticeable effect [from the regulations] so far,” Jane says. “It seems like the number of people who sell WMPs is growing here.”

Out of Sight

Confusion abounds on the definition of China’s version of wealth management, and, for that matter, on that of its shadow banking sector.

When banks around the world take money from depositors, those deposits go onto bank’s balance sheets. The deposits, guaranteed by the bank, earn interest (often at low rates) and the funds are lent out to a wide spectrum of borrowers.

But banks also take in funds that don’t go onto the balance sheets. This is the starting point for shadow banking and the WMP market. These funds aren’t called deposits, aren’t always guaranteed by banks but often earn far higher interest than deposits depending on what banks do with them. Perhaps, most importantly for China’s banking system, these funds aren’t detailed in official credit data, making them seem at times invisible.

In 2011, China’s central bank, the People’s Bank of China, began issuing a monthly data report called total social financing, or TSF. The metric is the widest count of credit data available for China’s financial universe and includes a gauge on ‘non-financial lending’, giving economists at least some sense of what goes on off the bank’s balance sheets.

The non-financial lending at banks has come to be known as shadow banking but, as Standard Chartered Bank noted in a report earlier this year, it’s better understood as the “shadow activity” of a bank. Shadow banks in their truest sense exist yet the term denotes unregulated lending houses so deep in the umbra that no official data captures their activity.

Mountain of What?

In truth, wealth management at banks can be a healthy form of financial innovation in developed markets, while also providing credit to needy borrowers willing to pay higher interest rates. The alarm stems primarily from the exponential growth of this quasi-regulated environment, coupled with a heightened sense of risk in the market.

Experts such as Andrew Collier, Chief Executive at Hong Kong-based Orient Capital Research, have pointed out the deep linkages that WMPs, trusts and shadow banking in general have with other markets, like land, exposing the country to a high rate of risk.

Banks took advantage of the loosened monetary policy following the 2008 financial crisis to begin promoting WMPs as a way for depositors to get around the centrally imposed, and artificially low, interest rate on deposits.

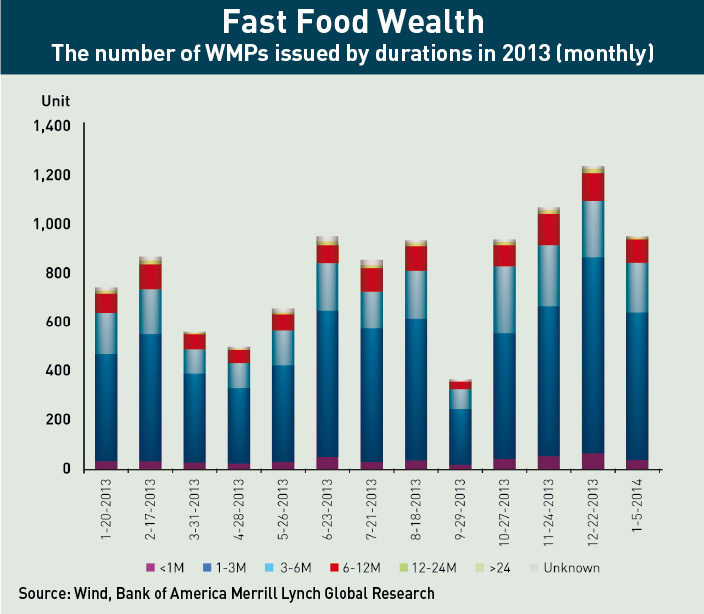

The deposit rate is set at an annual 3.3% but inflation often reduces the rate to around zero or even a real annual loss in savings. On the other hand, bank-issued WMPs offer between 5-7% annualized return. Trust products yield an average of 9-11% annually.

Statistics from the central bank show that the threshold investment for a WMP is usually around RMB 50,000, opening the market to many middle-class Chinese from the mainland’s developed eastern provinces.

At between RMB 500,000-RMB 1 million, trust companies have marketed their products to a wealthier group of individuals. Both have sold quickly.

TSF data shows that shadow lending at China’s banks has expanded six-fold since 2008 to about RMB 10 trillion in assets under management, according to research firm GaveKal Dragonomics. Trust products have increased by nine times in the short time period. The outstanding value of this kind of investment product, which is issued by trust companies but often sold by banks, also stands at around RMB 10 trillion. The expansion rate of off-the-books financing has far outpaced that of their plain-vanilla equivalent, deposits.

Unstable Empire

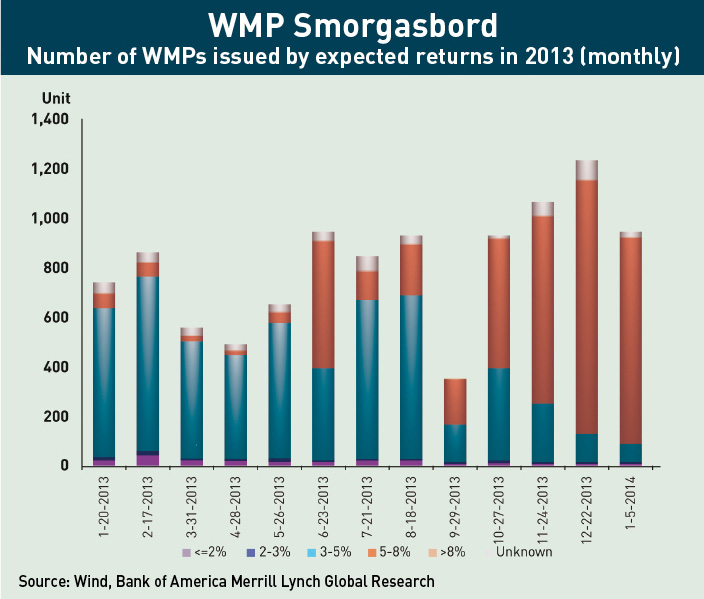

It’s not just size. The inherent risk of the wealth management market can’t be overlooked. One of the main concerns over WMPs is their maturation period, or the duration of time between when the investment is made and when the principal is paid back along with interest. For China’s WMPs, that period is extremely short. Up to 80% of the products in the market have a lifespan of one to six months, according to a research report from CLSA Pacific Markets.

Very few assets can produce an annualized return of 5-7% within a three-month period. To meet customer demands, banks have pooled these assets, sometimes paying off old products with the creation of new ones. “This is similar to a Ponzi scheme in a sense,” Patricia Cheng, China head of CLSA financial research, said in the report. “The way these things are written, if you look at the details, they’re really like spider webs. They create a cobweb that ensnares many parts of the financial system,” says Collier, also the former president of Bank of China International in the US.

One potential risk that Collier is researching is the role of land in the trust market, which spills over into WMPs. Throughout the trust market, land is often the target investment, or used as equity or collateral, meaning much of the real value of WMPs is locked into the property market.

For years, China’s real estate market has seemed like a safe bet, with prices in major cities climbing by more than 20% year-on-year for several years. But in 2014, the market has appeared to reach a tipping point after a decade of over-investment. Price growth has slowed and even fallen in some cities. Corporations with leveraged investments into real estate have never been more fearful.

“If property values decline by 10% to 15%, then all of a sudden, across many parts of this shadow banking empire, the collateral, target investment or whatever, is suddenly going to be worth 20% less,” says Collier. “It will have a huge impact on the entire system.”

Just Ordinary Folk

Despite the high level of risk, WMPs seemed to go unnoticed until a fateful day in December 2012, when banks, regulators and investors got their first taste of what the products were really made of.

RMB 200 million worth of products sold by Huaxia Bank nearly defaulted toward the close of the year. Photos in the Chinese media showed fearful investors gathering at the Jiading branch in Shanghai with the hope of retrieving their cash. Barclays Bank was quick to note that Huaxia’s faulty product was actually not a wealth management product but a private equity investment fund product. Still, analysts at global investment banks waited to see how regulators would react to the distress at the bank. Officials at Huaxia said the products had been sold without authorization and the bank, with the government behind it, eventually bailed out investors.

Instead of iterating the potential risk lurking in such loosely regulated products, the government gave an implicit yet strong guarantee to the industry. Sales were hardly affected. That’s another major criticism of WMPs. The people that buy into them often think of them as deposits that are guaranteed by the bank, which in some cases can be seen as guaranteed by the government. However, many of the products are not guaranteed and a default could result in real losses for real people, not just for banks. “Most of them are just normal people,” Jane at the local Shanghai bank says of WMPs buyers at her branch.

Many ordinary people who would otherwise put their money in deposit accounts buy products with a guarantee on the principal, she says. Wealthier—not necessarily more experienced—people often buy higher-yielding products without guarantees.

Another product went belly up in Suzhou last July. The local branch of ICBC was selling an entrusted loan product with a projected annual return of up to 15%. When the WMP went bust, the bank told its clients, all of whom had invested at least RMB 1 million, that it was not guaranteed. But regulators once again couldn’t bear its people, even wealthy ones, taking the hit. Although not made public, a Standard Chartered report said that officials pushed ICBC to bail out many of the investors.

Things Fall Apart

The third time was the charm—at least in eliciting a response from investors. In January, a $496 million trust product issued by China Credit Trust and sold by ICBC came to the cusp of default, putting at risk both the principal and interest owed to 345 wealthy investors. The product, a loan extended to coal miner Zhenfu Energy Group, carried 10% interest and a three-year maturity period. A legal battle had halted Zhenfu’s equipment two years earlier, which subsequently deteriorated; the price of coal plummeted and repaying investors became impossible.

A mystery buyer eventually bought up the junk products via ICBC but the damage to the trust industry was done. Trust loans, one of three categories of non-financial credit at banks, fell that month while the two other categories that feed WMPs, entrusted loans and bankers acceptances, surged to record highs, according to central bank data. The shift showed that the near default of China Credit Trust in the same month had flustered investors.

And the trepidation didn’t stop there. In February, total social financing took a sharp downturn. The People’s Bank of China (PBOC), China’s central bank, said the TSF fell to RMB 939 billion in the second month of the year from RMB 1.7 trillion a year earlier. That month, non-banking finance made up a mere 17% of the total credit picture, down from 43% in January and 42% in February 2013. Investors were finally catching on to the potential risk imbued throughout the WMP market.

“It seems that the rising default risk has started to erode Chinese investors’ confidence,” Wei Yao, China Economist at French bank Societe Generale, told investors in a note at the time.

At the same time, regulators have been hitting the market with new rules. The strongest of those may be yet to come. The China Banking Regulatory Commission (CBRC) took an initial swing at the WMP business in 2009 by stopping banks from dealing directly with trust companies. The crackdown didn’t work as planned. In response, banks simply restructured their products through securities companies. The massive increase in WMP funds moving through securities companies was the result of closing the direct passage between banks and trust companies. Now banks bridge funds through securities companies before moving them into trusts, something that has arguably increased the opacity of the industry.

The next significant attack on WMPs came in April of last year when the banking regulator issued the so-called “document No. 8”, which divided the market into what the CBRC called “standard” and “nonstandard” products, an entirely new distinction. The “non-standard” label pointed at loans structured through trust products that are generally used as a channel to provide financing without capital, one of the most risk-laden breeds of WMPs. Banks were asked to limit non-standard assets to 35% of their outstanding WMP balance, or 4% of total assets under management. They were told not to pool funds and instead manage the assets product by product so that regulators could see what constituted a specific product.

Again, hungry bankers circumnavigate document No. 8 relatively easily. A bank can simply sell non-standard products to a third party such as a broker then buy them back, a move that brings the asset into the standard category.

Masters of Illusion

Today the WMP industry exists in a state of unease and the CBRC may be winding up to deliver another blow to the wealth management industry, although itʼs unclear when that will come. Last November, Chinese media reported on a “document No. 9” that had recently appeared on the desks of executives at the country’s biggest banks, a follow-up to document No. 8.

At the time of reporting, the full blow of document No. 9 had yet to be felt but Chinese media said that the CBRC will likely take aim at the interaction between China’s WMP market and the interbank market. Part of the expected regulation was issued on May 16 in a notice called document No. 127. These new rules should have a mild effect on a relatively new product—and a nuisance to regulators—known as trust beneficiary rights, or TBRs.

During the past two years, banks have become increasingly clever in disguising their activity. Banks structure TBRs through the interbank market as well as through a third party in order to keep regulators off their backs.

TBRs are actually on-balance-sheet funds, or deposits, but by moving them through the interbank market they can be invested like WMPs. This presents a hall of mirrors in the hunt for growth in WMPs; the decrease in off balance-sheet lending in April didn’t account for this trick. In fact, that same month, banks had increased their exposure to TBRs by 57% year-on-year, according to a report from J.P. Morgan.

Document No. 127 will force banks to structure TBRs differently, ultimately labeling them with a higher degree of risk that will make the products more costly to invest in. However, May Yan, an analyst at Barclays, said in a research report that new rules should have a “neutral impact as they do not include some strict measures the market had previously speculated about”. Industry insiders may have reported demand for WMPs among urban Chinese people, but prospects of tougher regulations and an end to government backing for some of the products have made banks skittish. In late February this year Fuzhou-based Industrial Bank stopped what’s known as “mezzanine” financing to property developers.

At the time, the move was interpreted as a sign that the bank was skittish on the property sector. However, mezzanine finance is a creative form of high-yielding, unsecured off-balance-sheet lending which could stand to get hit by new regulations. The slowdown in the issuance of these loans could be more closely related to risk in the WMP market than in the property market. Management at some banks has even stopped financing off-balance-sheet activities, Head of Research at JL Warren Capital Junheng Li said in a note to investors earlier this year.

The slowdown in off-balance-sheet lending can be attributed to both a heightened sense of risk and the prospects for an imminent issuance of new rules, such as Document No. 9, says Chen Xingyu, a Shanghai-based analyst at Phillip Securities. That said, the latter may have caused much of the slowdown experienced in the first quarter of 2014. The outlook for China’s WMP market, in the short-term at least, is slower and more-tightly regulated.

“We think new regulations will strictly control new products. In the future, most of the strategies for these products will be based on conservative views,” Chen says. “The most important thing now is that the authorities realized that this is a huge potential risk, not only for the banks but also for the whole financial system.”

The Right Direction

Regulatory hiccups are unavoidable, but judging by trends in the money management industry in more developed economies such as the US, the flow of cash from on to off the balance sheet is likely permanent, even necessary for banks to stay profitable in a more competitive environment.

The wealth management industry in the US exploded in the early 1970s with the advent of the money market fund, which, much like China’s WMP industry, sought to circumnavigate centrally set interest rates on deposits by investing in short-term debt. Money market funds drew cash off the banks’ balance sheets and put it generally into US treasury bills. In 1977, financial services firm Merrill Lynch introduced the “cash management account”, a milestone in financial innovation. These money market funds gave customers a check-writing option, an innovation that began supplanting the function of banks.

“Essentially that service can replace banks,” says Chen Long, a professor of finance at Cheung Kong Graduate School of Business. “Right after that, money market funds had explosive growth.”

By 2001, money market funds in the US held four-times that of checking accounts at banks, Chen notes, demonstrating the movement of money off the balance sheets during the past 30 years. Such financial innovation helped US banks increase profits as the country liberalized interest rates.

China’s wealth management industry could follow a similar trend—assuming strong regulatory framework is in place. In 2012, China’s banks held RMB 122.4 trillion in assets, nearly four times the amount held by all other financial institutions such as brokers and asset managers, according to data compiled by CLSA. At present, Chinese banks are some of the biggest and most profitable in the world, owing in large part to low, government-set deposit rates. Yet, as the central banks move closer to a market-oriented rate, they’ll need to compete on interest rates, which will drive down their margins.

“In this age of interest rate liberalization, you need to find new ways to make money. These products are important to [the banks]. I don’t think they will shrink. I think money will continue to move off the balance sheet,” Chen Long says.

That’s the outlook for investors and banks, but from a regulatory standpoint, pumping more cash into the loosely regulated products is a worrying proposition. But between the CBRC, PBOC and China’s securities regulator, none are yet clear on the role that each will play in the wealth management market. “You need to have better coordination, in the sense that you can combine several regulatory bodies together,” Chen Long says.

But regulators in China routinely scuffle for control of certain industries—teamwork is hard to forge. Deflating risk in the wealth management market will prove difficult until the powerful bodies that govern China’s finances can come to terms with cooperating on market management.