How foreign banks in China are planning for the future in the light of a complex regulatory environment.

Many of the world’s largest manufacturers have set up storage units and factories in the Waigaiqiao Free Trade Zone about 20 kilometers from the bustling center of Shanghai, mostly to reap tax benefits. The quiet streets and subdued environment are little indication of the more than $100 billion in trade value that passed through the zone and two nearby free trade areas in 2012, roughly 3% of the country’s overall trade volume, according to a note from HSBC.

In early July, China’s State Council said it planned to turn the three zones into a single financial space where market forces will reign more freely than anywhere else in the country. In practical terms that would mean allowing free conversion of the renminbi and speedy establishment for wholly-owned foreign banks, among other things.

The Shanghai Free Trade Zone rules will supposedly house the country’s most relaxed banking and exchange rules, allowing international banks to capitalize on the offshore services that make them successful on the global stage. Foreign banks have sought such reforms since the 1980s, while slowly being allowed back into the mainland market after decades of exclusion.

Premier Li Keqiang has lauded it as breakthrough reform and even reportedly fought against banking regulators to push the plan through. But even so, it would be little more than an oasis of free market forces in an otherwise harsh regulatory environment that has kept foreign banks from establishing themselves in the sought-after retail and commercial bank industry.

“It will just be a bubble for reform. Outside [of the zone] will stay the same,” or remain unreformed, says one Shanghai-based banking insider, who asked to remain anonymous due to the sensitivity of the topic.

Managing Expectations

The records of the biggest foreign banks in China say they have operated on the mainland for well over a century. Standard Chartered says it opened its first office in 1858. HSBC Holdings traces its roots back to 1865 in the two cities of its namesake, Hong Kong Shanghai Banking Corporation.

Of course, in the 1950s after the Communist Party established New China, only a few foreign banks were allowed to stay in the country under strict confinement. Four decades later in 1995, a handful of foreign banks asserted themselves on the mainland via partnerships with domestic banks, mostly those that had long-standing ties with China. Today, they constitute the country’s biggest foreign banks: HSBC, Standard Chartered, Citibank and Hong Kong’s Bank of East Asia.

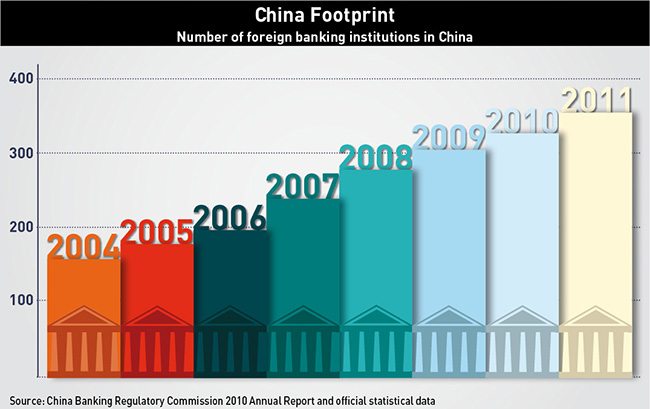

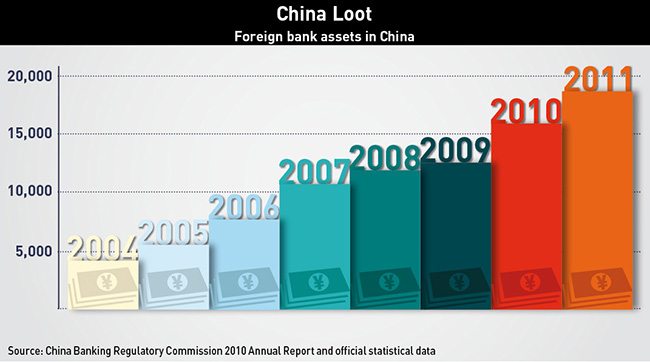

Other banks rushed into China in the late 1990s when the government allowed foreign banks to set up representative offices and subsidiaries. By early 2000, there were 191 representative offices and subsidiaries with $36 billion in assets, according to documents from the Cato Institute, an economic think tank based in Washington, DC.

“People were excited about the WTO [World Trade Organization accession]. They could see the market was about to change,” recalls Noyan Rona, the Chief Representative at Garanti Bank’s representative office in Shanghai. Garanti Bank is Turkey’s second-largest bank and entered China during the initial rush in 2000.

The WTO Letdown

When China became a member of the WTO in December 2001, regulators promised to let foreign banks expand around the country, deal in the local currency and launch real retailing business within five years. They also said banks could apply for wholly-owned local incorporation.

On the eve of the five-year deadline, China Banking Regulatory Commission (CBRC) even told nine foreign banks to prepare to be incorporated, a 2007 report from consultancy KPMG showed.

Today, much of the hope for a foreign banking boom has all but subsided as promises go unfulfilled under the large shadow of Chinese banks.

In 2012, foreign banks held only 1.82% of the total $21.46 billion industry assets, according to CBRC’s latest industry report. What’s worse is that figure shrank from 1.93% in 2011, down from a peak of 2.38% in 2007. At the end of 2011, China hosted 37 fully incorporated foreign banks, a flat line since 2009, according to the report. According to a 2012 IMF report, the emerging market average for foreign bank assets is 49% of the total bank assets.

In mid-July, Deutsche Bank, with more than $2 trillion in total assets, shuttered its last retail branch in Beijing, a bad omen for the industry as a whole. Deutsche Bank declined to comment on the closure.

On and Off Paper

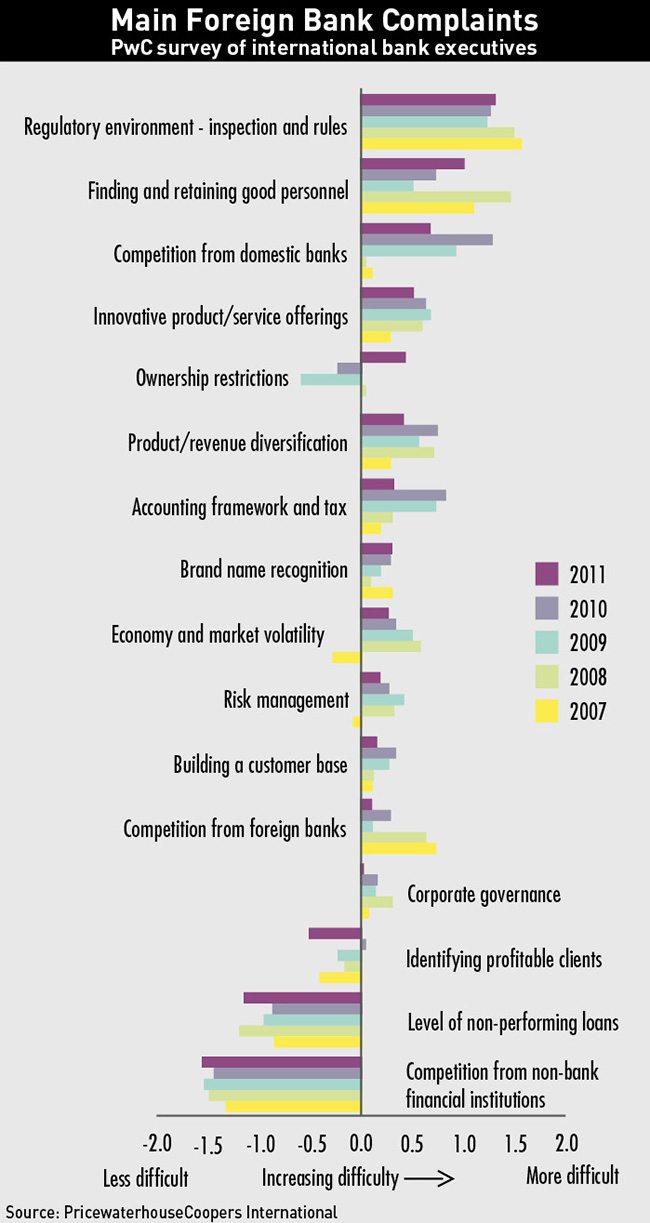

The dreary outlook can be attributed to over-regulation on and off paper. During the past five years, regulators have increased the level of regulation for both domestic and foreign institutions while giving less guidance, says Dennis Chan, Deputy General Manager of Nordia Bank in Shanghai. Stockholm-based Nordia has one branch in Shanghai and a representative office in Beijing.

In 2010, the CBRC issued stringent rules on working capital loans so that loans of more than RMB 10 million would reach the real economy and not be immediately appropriated into investments like real estate.

“I have never seen this before in my past banking experience,” says Chen, who has worked in the Chinese banking sector since 1994. “That regulation could very well help local banks. But for foreign banks, they normally have better credit control than Chinese banks. This limited the way we operate.”

But difficulties extend beyond the regulations on the books. Foreign banks will struggle to get routine paperwork approved by authorities, says one insider who asked to remain anonymous. Approval can take long periods of time, standards change constantly and often arbitrary requirements are included. Most frustrating, this person said, is how procedures differ between cities.

“Every step costs the banks money. And it’s no small cost,” the insider says. “On paper they have met the [WTO] obligations. But in practice they are still far off.”

Furthermore, the past 10 years of economic reform have not included China’s judiciary, and the legal framework that binds foreign business in the country remains weak, according to a paper issued last year by the European Chamber of Commerce. This can be a precarious environment for the foreign banks that support these businesses.

Running the Gauntlet

If conditions seem rough for big banks like HSBC, small banks are all but disqualified. The four major foreign banks that operate in China have an 85% hold on China’s foreign bank market, leaving the other foreign banks with a tiny percentage of the total market.

One reason is the CBRC requires all entrants to have at least $20 billion in total assets before they can even consider applying, and then the application is fraught with steep costs and roadblocks.

The first step is opening up a representative office. Banks will need to maintain $30 million in reserves. The CBRC requires the banks to deposit 40% of their capital at the central bank for safe keeping should they default, a unique requirement in the international banking market. In many developed markets, foreign banks are held to the reserve requirement of their home country, though this is changing in the US and UK where foreign bank fallout after the 2008 financial crisis has prompted a reevaluation of the rules.

Only after three years as a representative office can a bank apply to open a branch in the country. This kind of bank is limited to doing trade finance and letters of credit. Also, these branches aren’t permitted any transactions in RMB. Whether lending to foreign companies or Chinese firms, loans and deposits must be denominated in their respective foreign currencies.

The most difficult restriction in the ongoing application process is that the banks must turn a profit during this time. After three more years of income-generating operations, a bank can apply to lend in the local currency.

The high reserve ratio and 40% of the banks capital deposited at the PBOC can make the first three years of business difficult, and the slow process discourages expansion and keeps smaller players from growing in the market.

“To be honest, it’s very difficult here for many reasons. The bigger [banks] that succeeded, I think it’s because they were able to get more licenses to operate other forms of business [such as credit cards],” says Jean Thio, a partner at law firm Clifford Chance in Shanghai, who specializes in banking and capital markets. “The bread and butter of the business is hard to do without a large distribution network.”

Carving a Niche

Without the option of retail and commercial banking, many banks with small presences in China cater almost exclusively to trade between China and their home country. Garanti does letter of credit verification for Chinese and Turkish businesses trading goods between the two nations. It does not have retail branches, nor does it plan any foray into this market in China.

Bigger banks like Citi have continued to specialize and offer new products, like Citi’s mutual funds and credit card business. But progress in niche banking is hit-and-miss in China. Approvals for new kinds of products come on a case-by-case basis.

Citi’s branded credit card is an exception to the rule. Only Citi and Bank of East Asia have been allowed to issue cards that aren’t part of a joint venture with a Chinese bank. Visa’s and MasterCard’s ventures into branded cards on the mainland have forced them to partner with UnionPay, the payment platform owned by a consortium of Chinese banks that dominates the domestic payment processing market.

In June, industry insiders cried foul when China’s central bank stopped a payment platform other than UnionPay from processing MasterCard transactions. Once again, China was accused of not living up to its WTO obligations.

One clear answer for the big-name foreign banks is private banking. These financial institutions have done well using their reputation to attract high net-worth individuals who are wary to put all their money into Chinese banks. At HSBC, the minimum amount required to open a private account is $100,000.

“They normally have a very big brand recognition. As soon as they set up shop, they have credibility,” says Liu Jing, Professor of Accounting and Finance at Cheung Kong Graduate School of Business in Beijing, of foreign banks and their ability to pull in rich Chinese customers. “Their footprint in China might be very small but their brand is very big.”

Big Bang Theory

These trends point to the fact that foreign banks are far from reaching their full potential and still waiting on major reform in China.

In early 2012, Chinese state media published a five-point plan for reforming the financial sector. At the end of the list—and lacking a clear date—was the plan to liberalize the renminbi. The People’s Bank of China and the State Administration of Foreign Exchange has tight control over the currency’s use. Since 2008, the regulators have slowly allowed for cross-border trade in RMB, starting in Hong Kong and culminating in RMB 1 trillion circulating outside the mainland this year.

But most of those transactions take place in Hong Kong and hardly allow for foreign banks to conduct the kind of international transfers necessary to support a mainland-based global financial hub, which is what regulators say they want Shanghai to become by 2020.

“With international banks, their advantage is really doing banking on the international stage,” Liu says. “But China really restricts how money flows in and out of the country. That tempers their competitive advantages. I think that’s the biggest challenge.”

To China’s regulators, there are several examples nearby of how, and how not to liberalize a currency. When Thailand opened its capital account in the mid-1990s, the country experienced a quick influx of cash from international investors, only to see that capital flow out just as rapidly a few years later as questions over the country’s financial stability mounted. That outflow would lead to the Asian financial crisis of 1997.

South Korea, where foreign bank assets averaged 20.5% of total country assets between 2004 and 2009, took a much more gradual approach to opening its market, according to International Monetary Fund documents, slowly pushing through reforms between 1988 and 1996. Much like China, Korea used ceilings on lending rates to channel cash to specific sectors. The full convertibility of the won has brought in many foreign banks and their expertise, transforming Seoul, South Korea’s capital, into a regional financial hub.

But South Korea’s financial market is a good deal smaller than China’s, housing only 37 foreign banks, 15 of which came under investigation in late 2011 after the central regulators raised concerns over the volatility that foreign bank-led capital flows bring to the market. China’s own banking regulators likely consider such a scenario as they ponder reform.

Real Reform

The Waigaiqiao Free Trade Zone will be a testing ground for reform on a national level, according to a late August report from HSBC. The bank says the time is ripe for such sweeping change. About 16% of China’s cross-border trade was settled in RMB in the first half of the year, up from 12% during the same period last year. Alex Fuste Moto, Chief Economist at Andbank in Andorra, said in a recent report that cross-border trade in RMB would hit 40% within five years, a factor that will pressure regulators to act.

In that respect, the country is bursting at the seams with demand to do business in RMB, and foreign banks are ready to facilitate that business. This much is evident to technocrats in Beijing, but willingness to relax control is questionable.

PBOC and CBRC are more than financial supervisors. The overarching regulators are also some of the most powerful political organizations in the country. Freeing up the banking market and liberalizing the renminbi jeopardizes their importance in the economy, something they will certainly resist.