China’s growing middle class is spending more and more each year, helping the country transition to a consumer-driven economy. But how much of this extra consumption is being fueled by debt?

China’s growing middle class is spending more and more each year, helping the country transition to a consumer-driven economy. But how much of this extra consumption is being fueled by debt?

At first glance, Bonnie Cao and her husband look like cookie-cutter examples of China’s newly prosperous middle class. Cao works in public relations for an investment company in Beijing; her husband is an officer in the People’s Liberation Army. For years, the couple put half their income into a savings account each month, until finally, early last year, they achieved their dream of buying an apartment in the Chinese capital.

But as Cao told the South China Morning Post in August, things aren’t quite so simple. To purchase the small studio, the pair had to take on a nearly $500,000 mortgage, leaving them needing to make $3,000 monthly payments for the next 30 years. This is too much for them to afford, so they have rented out the apartment for $900 per month while living frugally at the husband’s army barracks.

Similar stories are widespread in China, complicating the wider picture of a rapidly-expanding middle class and an economy shifting away from exports and investment toward domestic consumption. Average yearly wages in China more than doubled between 2009 to 2016, from RMB 32,700 ($4,900) to RMB 67,600 ($10,100). McKinsey predicted in a 2013 report that rising income levels will help China’s middle class grow from 174 million people in 2012 to 264 million people by 2022.

The hope is that this enormous new cohort of middle-class earners will help drive consumption levels higher, providing a new source of economic growth that will help China escape the “middle income trap.” Catherine Wang, a project manager from Zhejiang province now based in Hong Kong, describes the middle class as “the key contributor to Chinese economic growth and China’s future.”

Yet some are worrying that the rise of China’s middle class will be derailed by the country’s runaway property market. Since 2010, Chinese consumers’ assets have risen in value by $12 trillion, thanks largely to the country’s booming property market. But this rise has been accompanied by a $2.4 trillion increase in household debt since 2012, with mortgage debt growing particularly quickly.

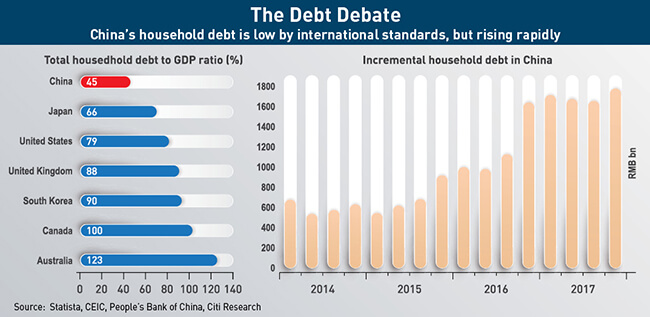

On paper, China’s level of household debt—estimated at 44% of gross domestic product (GDP)—is low by international standards. But the speed at which it is growing has a lot of people concerned. Citi Analyst Liu Ligang called the rise “alarming” in an October 10 note, and even the governor of the People’s Bank of China (PBOC), Zhou Xiaochuan, has warned that the “pace of growth [in household debt levels] has picked up in the last few years.”

Will the middle class be the source of China’s next phase of economic growth, or its next crash? The implications of that question for China—and for the global economy—could not be greater.

Great Expectations

The increased spending power of Chinese consumers is already having an impact—not only in China, but all over the world. The number of Chinese tourists visiting Italy, for example, has more than doubled since 2014, and stores are adapting by hiring Chinese-speaking staff and allowing customers to pay using Alipay and WeChat Pay, the popular Chinese digital payment apps.

In China, overall consumer spending increased by 10.5% from 2015 to 2016, much faster than the country’s GDP growth rate. This has led some excitable analysts to predict an “explosion” in demand for luxury brands and services from Chinese consumers over the coming years.

But this rise in spending looks less impressive when set against the nearly 30% rise in consumer debt and 23% rise in mortgages in the year to September 2017. Christopher Balding, an associate professor at the HSBC Business School, believes that there is a direct link between the two sets of figures. “There is pretty good evidence there is a not insignificant amount of consumption that comes through some form of debt financing,” he says.

Some see the rise in debt as simply a sensible way to facilitate consumer spending, a necessary part of creating a consumerist economy in China. “Most people see this as a positive development,” comments one Shanghai-based academic, who wishes to remain anonymous. “As long as China keeps growing, the middle-class club will grow bigger.”

This optimism is also fueled by an observable generational divide between a frugal and conservative older generation and a much more liberal post-1980s generation. These Chinese millennials live up to economist Milton Friedman’s notion of “wealth expectations,” in which expenditure habits are governed less by available means than by the expectation of future wealth. “People are not afraid to borrow money because they have a stable job and income,” says Wang.

In Search of China’s Middle Class

But there is a problem with the picture often painted of a rising generation of affluent young Chinese borrowing small amounts to spend on Louis Vuitton bags, expensive vacations and the latest smartphone, points out Andrew Collier, Managing Director of Orient Capital Research in Hong Kong.

“There is a funny thing about the middle class,” says Collier. “When I walk around China, I never see a middle class. What I see are wealthy people in a couple of big cities.”

McKinsey’s widely-cited forecast defines anyone with an income between $9,000 and $34,000 as middle class. But a large proportion of China’s consumers are at the low end of this spectrum, without the kind of disposable wealth that allows luxury purchases. What’s more, the report does not mention the elephant in the room—consumer debt.

For Collier, the steady rise in consumer spending is not necessarily evidence of a growing middle class, but rather the rapidly increasing wealth of a small elite. “You could argue that there is no middle class, or that it’s quite restricted. That it’s basically Bei-Shang-Guang,” says Collier, referring to the triumvirate of top-tier cities—Beijing, Shanghai and Guangzhou—where conspicuous consumption is readily visible. If you go to smaller Chinese cities such as Jinan, in China’s eastern coastal province of Shandong, by contrast, “you don’t get a sense of tremendous wealth, you get a sense of a few people who have some wealth,” he adds.

The concentration of wealth in the hands of a small minority is even clearer in the wealth management products market, where a lot of China’s middle class park their money. “Some data suggests that the rich control at least half the savings,” comments Collier. “Literally 1 or 2 or 3% [control] half the assets in the banking system. So, if you try to bring this stuff to bear, the whole notion of the growth of China’s middle class goes out the window.”

So how big is China’s middle class in reality? Balding says the answer depends on who is using the phrase ‘middle class.’ “If you’re talking about Victoria’s Secret, what percentage of people are going to be buying their products, that’s a very different number than the policymakers in Beijing consider to be middle class based on, say, a PPP calculation for the International Monetary Fund,” he says.

Millionaire Security Guards

Things become even more complicated when you take into account the effect of China’s red-hot property market, as Balding explains. “You cannot make assumptions in China,” he says. “Somebody dressed in Louis Vuitton might just be trying to show off and have no money, and somebody that is a security guard might be a millionaire.” He adds that the security guards at a university he knows are likely to be millionaires because they once owned the property on which the school is built.

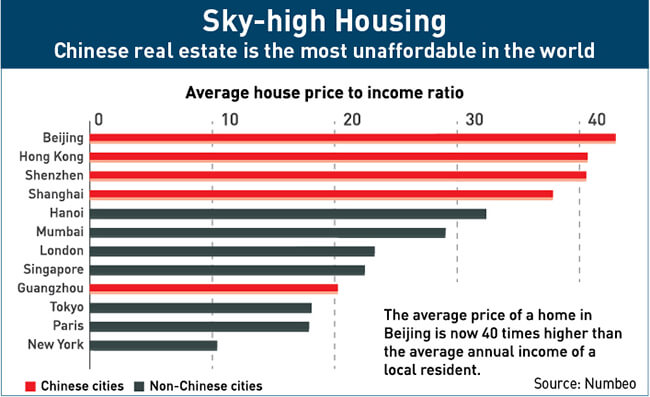

Housing prices in China have skyrocketed in recent years, with annual growth rates in some cities at times reaching 40%. At the peak of the price spike in 2016, one Shanghai resident reported buying a property for RMB 2 million, and seeing it gain another RMB 1 million in value within five months.

This growth has been fueled by a widespread feeling among Chinese consumers that property is the most—or perhaps the only—truly secure investment. “It’s part of the culture to own property,” says the Shanghai academic. “In fact, it’s a natural choice for people to buy property if they have the money.”

This impulse to invest in property is best demonstrated by consumers’ habit of buying multiple homes if they can afford it. “If you have spare money, you buy more properties,” says the academic. Collier remembers being startled when he asked a group of students in Jinan whether they owned a house. “Everyone said three or four, and then one girl said two, and the other girls laughed and said ‘yeah, but two big ones!’” he recalls.

For those who already own a home, this situation has worked out just fine, as the anecdote of the wealthy security guard suggests. But it is creating problems for others, especially young people who are finding it increasingly difficult to get onto the property ladder.

“If you bought even five years ago, you might have been able to reasonably afford it and have made good money,” says Balding. “[But] if you are trying to buy now in Shenzhen, you are buying upward of $1,000 a square foot… In Hong Kong that might not be crazy, but by any global standard that is a crazy number.”

However, the pressure to buy is extraordinarily strong for young adults in China, partly because there is universal expectation that prices will continue to rise. This implies that any delay will only mean paying even more later. There is also added cultural pressure in a society that considers buying a home a rite of passage, especially for young men. “Everyone, everyone, everyone, thinks in terms of property ownership,” says Balding. “People don’t get married until they buy an apartment.”

These twin pressures are tempting an increasing number of young Chinese to take on troubling amounts of debt in order to make that all-important purchase. “There are kids that are getting their parents to chip in and right out of school buying half-a-million-dollar apartments,” relates Balding. “I can ballpark what they make but it’s not remotely enough. They must be living on bread and water to be able to afford that.”

Collier has noticed a related but equally concerning trend, which is that a growing number of people “are taking their mortgage loan and using it for their equity down payment.” Aside from raising the risk of a property crash, Collier believes that the increasing speculation on property is harming consumer spending. “[Consumers are] starting to get significantly leveraged mainly to property, which means that they are going to have less income available for other kinds of expenditure,” he notes. “The data does support that. It’s very clear on trend.”

According to the Shanghai academic, the connection between soaring mortgages and falling spending couldn’t be clearer. “[The] rising value of property actually suppresses consumption,” he says. “People have to cut other costs in order to pay mortgages.” He shares that this phenomenon has even led to the coining of a new term in Chinese cities. “We jokingly refer to ourselves as fang nu, or ‘housing slaves’,” he says wryly.

This phenomenon is already harming China’s transition to a consumption-driven economy, according to Huang Xiaodong, Executive Vice President of Shanghai University of Finance and Economics’ Institute for Advanced Research. “Chinese households have generally been short on liquidity… in other words, the soaring mortgages have inhibited China’s economic growth to a certain extent,” said Huang in a recent speech.

But an even greater worry is that the country’s overleveraged homeowners may default on their payments, causing the country’s swelling mortgage market to pop in a similar manner to the US during the subprime crisis of 2007. It was just this kind of situation that PBOC Governor Zhou had in mind in October when he raised the prospect of a “Minsky moment” for the Chinese economy. He was referring to a phrase named after economist Hyman Minsky who believed periods of stability encourage risk taking, which can lead to a moment when there is a major collapse of asset values.

Debt Stress

Comparing China today with the US 10 years ago seems a stretch considering its household debt to GDP ratio is less than half the level America reached on the eve of the credit crunch. But Balding believes that China’s property market is reaching the stage where it is comparable to the Western economies. “New buyers are buying with Western normal levels of borrowing,” he says. “They might be buying with a 75% loan and a 25% down-payment.”

There is also anecdotal evidence of more corrosive practices, such as “people taking out loans, buying an apartment, going out and buying more apartments, borrowing off those apartments, buying more apartments,” relates Balding. But it is difficult to know how widespread this practice is, he concedes.

On the other hand, high mortgage-to-value ratios are a relatively recent feature of property transactions in China, meaning that any risk may be easily contained. “There is so little debt in previous generations,” says Balding. “[So, there’s] reason to think that the debt stress associated with apartments is concentrated among newer buyers.”

Another mitigating factor is that many young Chinese—even if they cannot easily afford their own home—have strong expectations of inheriting property from their parents and grandparents. This could underwrite the huge liabilities associated with the purchase of a new property.

Yet there is no doubt that the Chinese government is concerned about a housing crash. President Xi Jinping warned repeatedly throughout 2017 that “houses are built for inhabiting, not for speculation.” Cities across the country have also introduced restrictions on second home ownership in a bid to curb speculation.

But unlike other governments, which might lower interest rates to keep a lid on monthly mortgage payments, China is also attempting to ward off a crash by buying up large amounts of unsold units, according to a Wall Street Journal report. “Sixteen percent of all property purchases in 2016 were made by government entities,” says Collier. “That’s a lot of money they’re putting in. So, while they are trying to restrict mortgage loans, they are also jacking up the property market.”

Collier believes local governments are pursuing this approach because they need to bail out insolvent developers and shore up their own finances. “The bigger issue is that property supports local government revenues,” he says. “[If property prices] decline that would lead to that whole source of income dropping, which would be a huge problem for local governments across the country.”

The problem is that Chinese consumers also know this. This means that there is a widespread perception that the country’s property market has become “too big to fail,” further fueling the rush to buy.

Treating the Symptom

As 2018 gets underway, the Chinese government appears finally ready to tackle the country’s debt problem head-on. ‘Deleveraging’ has been the buzzword since the 19th Party Congress in October, with regulators releasing new guidelines and slapping record fines on misbehaving banks.

There are also signs that the government is trying to tackle skyrocketing house prices in major cities like Shanghai and Beijing. “The government is already changing this,” says Lu Ming, Professor of Economics at Shanghai Jiao Tong University. “Recently, they announced that… starting now, they are supplying more land for rental housing.”

The hope is that building more affordable homes will cool the rise in property prices, while encouraging renting will enable more people to pour their growing incomes into the real economy, rather than the financial black hole of the mortgage market.

But if the country is really going to rein in the real estate market and unleash the spending power of its middle class, there is much more work to do. “China has a great ability to organize politically to overcome challenges,” observes Collier. “But I do think that you can’t sustain leverage forever.”