China’s massive use of coal is a global problem. Can the country fulfill its goal of becoming carbon neutral by 2060?

The winter of 2020 was brutal. An unexpected atmospheric cocktail created in part by a warmer Arctic made the mercury plummet to unusually low levels in China. In several southern cities long lines of workers climbed up the stairs in their office buildings, feeling perhaps the warmest they would all day thanks to the activity—elevators and office heating had been shut off due to power shortages.

The situation hasn’t been much better in northern China either. More than 2.5 million households across Hebei province were converted from coal to electricity or natural gas in 2017, but gas shortages and a lack of infrastructure disrupted the operations of industrial firms across northern China, and left some villages without heat amid sub-zero temperatures in the winter of 2018, forcing authorities to suspend the conversions.

Meanwhile, in September, China’s leader Xi Jinping made an ambitious pledge to reduce China’s dependence on coal, currently the country’s main energy source, in order to peak carbon emissions by 2030 and achieve net zero status by 2060.

The answer to both the power shortages and the need to limit carbon gases is to cut coal usage and boost renewable energy sources. China is rapidly ramping up investment into alternatives to coal-fired energy production, but it has a long way to go. While coal usage is plummeting in much of the world, coal still accounted for 58% of China’s total primary energy production as of 2019. This was actually an improvement over the past—the share of coal in China’s energy mix had already declined from 80% in 2010. However, China still currently has around 1,080 coal-fired power plants in operation, around half of all coal-fired plants in the world, and the number is still growing.

In 2020, China put 38.4 gigawatts (GW) of new coal-fired power capacity into operation, more than three times the capacity put online in the rest of the world combined, Reuters reported. The plants had been approved long before Xi Jinping made his carbon-neutral announcement, but the reality of China’s energy landscape clearly does not yet match its ambitions. Whole provinces as well as millions of workers still depend on the coal business, as well as the power grid.

China’s power paradox

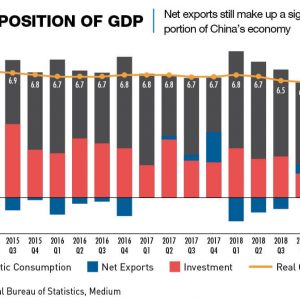

Lauri Myllyvirta, lead analyst at the Center for Research on Energy and Clean Air, an independent climate tracking organization, says Xi’s pledge to make China carbon neutral by 2060 was surprising given the country’s urgent need for energy to fuel fast economic growth, particularly given the nature of growth in the past few years. “This [growth] had been very energy intensive, driven by construction and heavy industry, resulting in increased fossil fuel investment, including coal-fired power plants. COVID-19 just made those trends a lot more pronounced. So what Xi Jinping was announcing was really a complete change in direction.”

China is currently the world’s largest consumer of energy, the largest producer and consumer of coal, and the biggest emitter of carbon dioxide. While climate experts the world over have applauded China’s long-term goal to shift towards renewables, it comes after 40 years of breakneck economic growth fueled largely by coal.

From 1990 to 2019, the country’s coal consumption nearly quadrupled. Since 2011, China has consumed more coal than the rest of the world combined, and the China Electricity Council predicted in February that the country would use 6-7% more electricity this year than in 2020.

On the other side of the ledger, China has for several years been the clear leader in investment in clean, renewable energy, and already produces more energy using non-coal methods than the United States. Energy output using wind, solar and hydropower are all growing fast. Xi’s September 2020 statement was an acknowledgement of China’s role in the global climate emergency, and Premier Li Keqiang later said that an action plan would be drawn up this year to meet the 2030 target. Drastically reducing the use of coal to create electricity will be a crucial part of that plan.

“The transition towards a low-carbon electricity system is a mainstay of China’s bid to become carbon neutral before 2060,” says Muyi Yang, senior Asia electricity policy analyst for the energy research firm, Ember, and an author of a recent report on China’s increasing coal capacity. “This requires substantial changes to be made in the generation technology-fuel mix to replace coal and other fossil fuels with non-fossil fuels. Making these changes requires a reconfiguration of the wider electricity and economic systems, as already recognized by the central government.” The process of phasing out coal is extremely complex, given the way in which the fossil fuel is embedded in China’s system, he says.

“It is also worth noting that promoting coal phaseout and electricity and economic reconfiguration require sound and effective policies,” adds Yang. “Making these policies require, among other factors, closer coordination and collaboration both horizontally between government agencies, state-owned enterprises, and private actors, as well as vertically across different levels of government.”

An insufferable reliance

The country’s domestic coal supplies mainly come from the northern provinces of Shanxi, Shaanxi and Inner Mongolia, with the industry dominated by state-owned enterprises (SOEs) such as the China National Coal Group and the China Energy Investment Corporation. Energy security is a key concern for Beijing, and huge investment and preferential government policies, such as imposing quotas on coal imports, have helped keep the price of domestic coal high, protecting both the industry and the jobs within it and reducing reliance on imports.

With a shift in focus in energy policy, this preferential treatment for coal production is expected to be phased out, leading to a financial vacuum in certain provinces requiring deep population and economic changes.

“Some resource-dependent regions and mining towns may bear much of the costs associated with coal phaseout,” says Yang. “Low-carbon technology industries are more likely to create jobs in close proximity to energy demand centers [in the east], and the skills and knowledge required by low-carbon technology industries are quite different.” But local authorities are reluctant to retire inefficient fossil fuel plants in a bid to keep both the energy system and the economy stable, and those in the industry are keen to profit while they still can.

One solution touted by those determined to see coal continue to play a role in China’s future energy landscape is carbon capture technology, whereby emissions are either stored underground or used to create new industrial products. But while China’s newest coal plants are some of the most clean and advanced in the world, such technologies are still a long way from being economically viable. “The costs are just too high to do that across all of China’s power plants,” says Alvin Lin, China climate and energy policy director for the Natural Resources Defense Council, a US advocacy group.

A more successful scheme can be found in Yunnan, where coal contributes just 20% of power generation. To make up the difference, local hydropower stations deposit one Chinese cent into a “standby fund” for coal plants for every kilowatt hour of electricity they generate. While such actions could be seen as a compensation mechanism for outdated technologies, it at least gives coal plants not yet ready for retirement a pathway to withdrawal from base load operations.

China will need to shut down at least 600 coal-fired plants in the next 10 years and replace them with renewable electricity generation if it is to achieve net carbon neutrality by 2060, according to a report by climate analytics provider TransitionZero released in April. The Draworld Environment Research Center, meanwhile, says that to meet its 2030 target, China must shrink its current coal-fired power generation capacity from 1,100 GW to around 680 GW immediately, stop building new coal power plants and double wind and solar energy in order to reach its 2060 goal.

Switching on the sun

The provinces that rely on coal for their economies will ultimately need to diversify their economies, and there are signs it is happening. Even Shanxi province in the mining heartland of China has been investing heavily in solar energy, electric vehicles, high tech manufacturing and tourism in recent years. “If you’ve got an economy that’s just too reliant on one kind of resource, then it’s going to be a fragile economy when the demand falls for that resource,” says Lin. “Shanxi realizes this and has been looking at how to upgrade its economy.”

In 2020, China added a record amount of wind and solar power, almost double its 2019 figure, and has managed to reduce the share of coal in its energy mix from 70% a decade ago to 56.8% last year, even though absolute volumes rose. However, non-fossil fuels only met around 15% of China’s 2020 energy needs, with the vast majority of that made up of hydropower and nuclear, both of which come with their own set of ecological concerns.

The Chinese government has invested heavily in renewable energy research and China currently boasts the world’s highest number of renewable energy patents. It has also for years offered substantial subsidies to renewables, but these are now being pulled back as the renewable industry becomes mature and government support becomes harder to justify.

“True renewables like wind and solar only make up a tiny fraction of China’s current energy mix,” says Ma Jun, the director of Beijing-based NGO the Institute of Public & Environmental Affairs. “But with the economic downturn and many regions in a bad fiscal situation, it’s not sustainable for the subsidies to be given like before.”

The switch away from coal to renewables creates a lot of pain for the system in many ways. There are issues of generation reliability with renewable energy sources, as well as transport and distribution of energy, sometimes over huge distances from wind and solar power generation sites, mostly in the west of China, to urban centers, mostly in the east.

“In the short to medium term, yes, coal is not going away in China any time soon,” says Simon Nicholas, energy finance analyst for US non-profit the Institute for Energy Economics and Financial Analysis. “In the longer term, however, the fact that renewable energy beats coal-fired power on every measure, including cost, means that towards the middle of the century, coal-fired power will be disappearing rapidly.”

A tough transition

With a clear plan of action still lacking, making the shift from coal to renewables will not come without challenges, given the heavy investment and dependence on the coal industry. “You have some provinces and SOEs that see the period before the 2030 peak as a window of opportunity to add new fossil capacity and grow emissions, as they think it will be easier to decline emissions afterwards from a higher base,” says Myllyvirta. “Then there are people in the environment ministry who take a more rational approach and think you have to start turning things around now. It’s really a tug of war between these two interests at the moment.” For China to meet the 2060 deadline, people in the bureaucracy and business who are taking a more environmentally-aware approach, will need to prevail.

But despite the challenges, in rhetoric at least, China’s climate goals are still front and center. In April, in fresh climate talks with the Biden administration, both President Xi and the country’s climate envoy Xie Zhenhua reiterated pledges to reduce emissions. And if the history of China over the past few decades has taught us anything, it is that the country is capable of major changes in economic and social strategies.

“The global energy transition is a challenge but China will be helped by the fact that many of its green and economic/energy security goals are well aligned,” says Nicholas. “Increased reliance on renewable energy improves energy security without the air pollution caused by burning domestic coal. Wind and solar are also increasingly the cheapest source of power generation.”

“It’s like a big ship trying to change course,” adds Ma. “It will take some time, but the most important thing is that all the political statements [on clean energy and the environment] are translated into action. It’s imperative for the world that the US, the EU and China can all sit in the driving seat and power this global effort forward.”