China’s fintech industry is evolving at a dizzying pace. The problem? Regulation hasn’t been able to keep up.

China’s fintech industry is evolving at a dizzying pace. The problem? Regulation hasn’t been able to keep up.

In early November, a chat group shared by Bill Deng and many other ex-employees of financial technology giant Ant Group exploded in disbelief. Regulators had suddenly slammed the brakes on what would have been Ant’s record-shattering $34 billion concurrent initial public oferings (IPOs) in Shanghai and Hong Kong.

“We were all in shock,” says Deng, who left Ant in 2017 to cofound XTransfer, a Shanghai-based B2B cross-border financial services platform. “The chat groups for Alibaba alumni went crazy.”

The blockbuster listing’s abrupt suspension also left would-be retail investors reeling after they bid for shares in Ant expected to be worth $3 trillion—more than the UK’s entire annual economic output. And it represented an unprecedented putdown of Jack Ma, days after the billionaire founder of Alibaba and Ant had publicly criticized China’s financial and regulatory system in a speech at a Shanghai forum. But in a broader sense, the suspension put the future of fintech under the microscope as regulators move to bring the previously runaway digital finance sector under control.

Jump-starting fintech

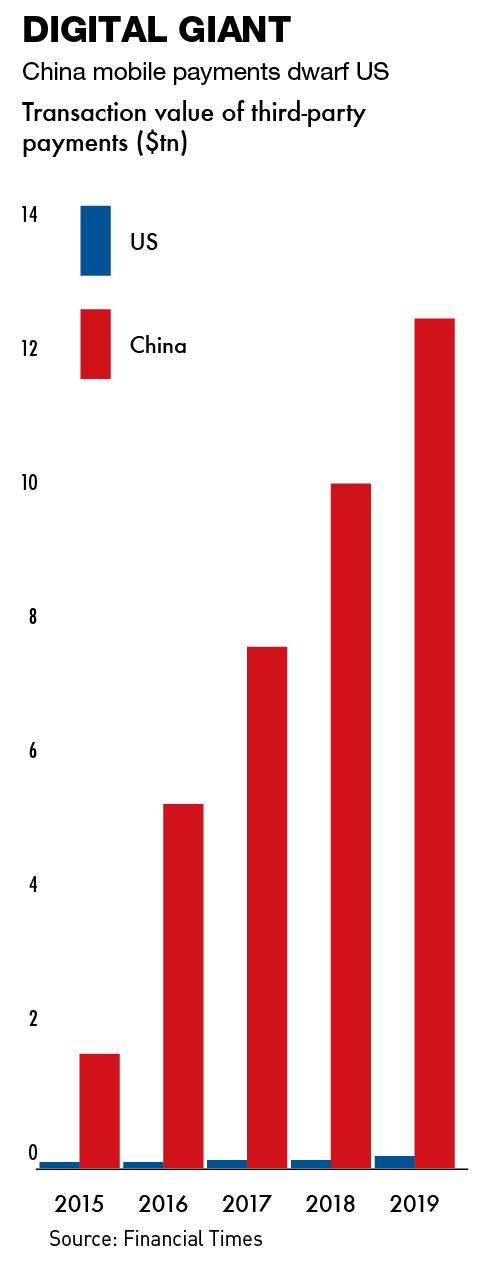

Ant—originally Alibaba’s online payments business, Alipay, which was spun off in controversial circumstances a decade ago—is the biggest player in a sector that has seen explosive growth over the past dozen years. The expansion is best illustrated through mobile and digital payments—in 2010, when Alipay was carved out of Alibaba, mobile payments barely registered on the radar. By March 2020, 776 million people were using mobile payment services, making purchases and sending cash digitally, with the vast majority using either Ant’s Alipay or WeChat Pay, operated by rival Tencent.

The rise of digital payments has helped China stake a claim to becoming the world’s first cashless society. Users scan a merchant’s QR code, or vice versa, to transact—an easy setup pioneered by Alipay and WeChat Pay at the start of the 2010s. They succeeded because the apps were able to ride on existing financial infrastructure such as bank accounts, bank cards, and clearing and settlement systems, according to the research firm RedTech Advisors’ founder Michael Clendenin.

Mobile payments flourished and even at the end of 2019 accounted for four out of every five payments, as well as more than half the value of all non-cash retail payments. Ant dominates digital payments, with transactions on its platform totaling RMB 118 trillion ($18.3 trillion) in the 12 months up to end-June 2020. Its Alipay app—essential for day-to-day life in China—has more than 1 billion active users and some 80 million merchants.

Fintech got its start in China by facilitating digital payments, but consumer finance is arguably where it has been most impactful. Ant notched up an early success after it spied an opportunity to allow consumers to earn a return on spare change in their Alipay account balances while allowing the funds to be also instantly redeemable for everyday purchases.

Fintech got its start in China by facilitating digital payments, but consumer finance is arguably where it has been most impactful. Ant notched up an early success after it spied an opportunity to allow consumers to earn a return on spare change in their Alipay account balances while allowing the funds to be also instantly redeemable for everyday purchases.

Historically, households invested most of their household savings in bank deposits and property, and many families had limited allocation of wealth outside these two asset classes. That changed in 2013 when Ant launched a money market fund—Yu’ebao, or ‘leftover treasure’—on Alipay, giving people access to money management tools even if they only wanted to invest RMB 1. For most consumers, it was their first financial investment product and a sign of more innovations to come from Ant.

Alibaba’s early success in embedding Alipay in everything from online shopping to utility bill payments paved the way for an expansion into lending. Typical forms of consumer credit in the West have not taken off in China: for example, three-quarters of Chinese aged 18 or over did not have a credit card at the end of 2019, while the same proportion of Americans owned at least one credit card.

This is where fintech companies such as Ant, Tencent-backed WeBank, Baidu’s aiBank, JD Technology and New York Stock Exchange-listed Lufax have revolutionized consumer finance in recent years.

“Getting rid of cash and making it convenient to pay by phone—that was only the warmup,” says Clendenin. But the biggest impact of fintech came from Ant’s decision to start extending credit in 2014-2015 after they felt they had enough information on their hundreds of millions of Alipay users to lower the risk on providing unsecured consumer credit.

“Credit is the grease for the economy,” says Clendenin. “If you don’t have reliable consumer and business credit flowing through the economy, then it’s not going to reach its full potential.”

Online lending facilitated by fintech heavyweights was virtually non-existent before 2014. But by the middle of 2020, loans extended through online platforms and tech firms had hit RMB 1.43 trillion, equivalent to 22% of personal consumption loans excluding mortgages and credit card debt, according to the People’s Bank of China (PBOC). The share has since grown to an estimated 30%.

The fintech giants leverage their tech expertise and stores of Big Data to back up lending decisions. Online platforms like Ant and WeBank employ artificial intelligence to analyze troves of data they access via their wider ecosystems to build user credit profiles that are much more accurate than traditional credit scoring. Machine learning has boosted the speed, efficiency and accuracy of risk assessments for loan origination.

Ant’s march

Ant has long been the leader in China’s mobile payments market, but the company’s IPO prospectus also underscored its dominance in digital financial services. The document revealed that in the span of a year, Ant originated loans to half a billion people and accounted for nearly a fifth of the country’s outstanding short-term consumer debt as of June 2020.

The company held a 12% share of China’s total addressable market for consumer credit in mid-2020, but 56% of the consumer credit market for mobile internet users and micro-to-small enterprises (MSEs), according to May Yan, head of Greater China financial research at UBS.

Other fintech companies are far less prominent, as reflected by Hurun China’s 2020 ranking of the top 10 fintech companies. Ant’s estimated market cap of RMB 2.1 trillion as of mid-October 2020 was more than double the combined RMB 994 billion valuation of the other nine companies. The gap has shrunk since regulators stopped Ant’s IPO, but the company remains a force. The remaining players are almost all incubated by Alibaba’s rival tech giants including Tencent, Baidu, JD.com and China’s largest insurer Ping An Group.

The strength of Chinese fintech firms makes the absence of foreign players even more conspicuous. But domestic companies were to a large extent able to steal a march on foreign firms in the early days of fintech in China through better execution and understanding of the local market, according to Zennon Kapron, founder of fintech research firm and consultancy Kapronasia.

“One of the big challenges for foreign companies is they come in with these foreign business models, and they assume that it’s going to work in China,” he says.

Cutting Ant down to size

The cancellation of Ant’s high-flying IPO shocked many, but regulators had been building a case for more than a year over the company’s consumer credit business model. While Ant can offer loans instantly using analytics tools that assess an applicant’s credit worthiness, the company itself does not supply the credit or make the loans—it merely qualifies the borrowers, originates the loans and then hands them off to more than 100 partner banks that actually carry the liability.

Clendenin says he was unsurprised when the hammer came down on Ant. “At the end of the day, there was a lot of moral risk to Ant’s old loan facilitation model. They were the middleman and simply taking a cut of the transaction. All the risk was on the banking partner, and that’s just not a sustainable model in any market.”

Even if the writing was on the wall, the speed with which the Chinese authorities moved to regulate fintech blindsided the sector. “Everything that happened toward the end of last year did take us by surprise,” says Yan from UBS. “It was both from the rationale that the government gave, as well as the severity and rapidity of how it happened. The rationale discussed by the government was that all these smaller banks were potentially taking on too much risk with wealth management products and lending products. And when you look at it from that angle, they had a point. The suspension of such an important IPO just spoke to the severity of the problem.”

The boom-and-bust of P2P underscores how new business models have the power to disrupt industries faster than regulators anticipate. There have been numerous instances in China’s thriving tech industry, ranging from how ride-hailing apps such as Didi upended the traditional taxi industry in 2014-2015, to the proliferation of shared bicycles on sidewalks in 2016-2017.

“Regulation always follows innovation,” says Clendenin. “I don’t think the regulator is being obviously unfair to Ant. No matter if you’re a regulator in China, Europe or the United States, you can’t let these fintech companies reach the point where they threaten to become systemic risks. They can’t become too big to fail.”

As well as aiming to contain risks to the stability of China’s financial system, the signs are that upcoming policies will continue to take aim at Ant’s dominance in digital financial services. “Network effects mean that fintech competition often leads to ‘winner-takes-all’ outcomes including market monopolies and unfair competition,” PBOC deputy governor Pan Gongsheng wrote in January.

Pan’s warning came a week after the PBOC released draft regulations on non-bank payment institutions that will allow China’s anti-monopoly authority to ban any payments company caught abusing a dominant market position. The rules also propose breaking up a company into separate businesses if it violates fair play rules.

A complete ban on the loan facilitation model popularized by Ant is unlikely. Instead, analysts believe that in the near-term, internet finance firms will be targeted for reforms on a case-by-case basis. The big banks, all basically state-owned, are likely to be cheered by the efforts to rein in big fintech firms—particularly after Jack Ma belittled the “pawnshop mentality” of traditional lenders in his Shanghai forum speech.

“The bigger banking partners that Ant has—and the banking system as a whole—did not like Jack Ma coming through and showing them up,” says Clendenin. “It was foolish for Ant to think that it could move into an industry where some of the biggest players are state-owned and threaten the businesses of banks without repercussions.”

The banks had watched with distaste as the new payment platforms siphoned off fees that used to go to banks—in 2018 state-owned banks lost RMB 318 billion in non-cash merchant fees to online and mobile payments, a figure that rose to an estimated RMB 402 billion last year, according to Kapronasia.

The billions of RMB in savings parked by consumers with fintech apps has also taken a bite out of the lucrative customer deposits that banks hold and use to fund loans. Ant reported RMB 4.1 trillion in assets under management as of mid-2020. While this was a fraction of total RMB 6.47 trillion of household deposits, it was growing fast.

Platforms such as Alipay and WeChat Pay have quickly penetrated everyday life to the point where they are part of the social fabric. This has raised thorny questions over their influence and social responsibility, in much the same way that Western governments are fretting over the blanket power of Facebook, according to Yan, the UBS analyst.

“Chinese culture has historically trended toward saving and being financially conservative. But the younger, internet-savvy generation has been influenced by the online lenders and their easy-access credit,” she says.

Leading digitalization

The looming regulatory shake-up for China’s fintech landscape does not seem to have killed off Ant’s potential listing entirely. And while heightened regulatory scrutiny will put the brakes on the fintech giants to some extent, there is still plenty of room for them to grow, with rising incomes feeding steady growth over the coming years in the country’s personal investable assets, insurance premiums and consumer and business credit segments.

“When it comes to the digitalization of finance, China is the most advanced,” says Bill Deng. “But all of it has just happened in the background and people are getting used to this digital lifestyle … their mindset has changed. It’s likely to be the same elsewhere.”

When it comes to Ant’s prospects, Deng is sanguine about his former employer’s ability to bounce back from the recent uncertainty. “It is not by accident that Ant has become so big,” he says. “It’s because they had support from the regulators. Both sides know this, so even if there are obstacles in the communications right now, each will do what is necessary to ensure Ant and the whole fintech industry continue to succeed.”