An abrupt slump in China’s exports in the first half of 2013 raises questions over the role of exports as the country’s main economic growth driver.

Business last year was the worst that Yang can remember since she began working for Yongli Suitcase in Wenzhou, a coastal city renowned for its freewheeling entrepreneurialism, eight years ago.

The RMB 40 million of goods the luggage maker exported in 2012 was a far cry from the heady days four years earlier. “The best year for our company was 2009, when we exported RMB 100 million,” says Yang, a salesperson who only gave her family name. Yongli’s struggles typify the reversal in fortunes that many small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs) have suffered in recent years. In the boom times, few Chinese cities soared faster or higher than export-rich Wenzhou, which came to be regarded as a bellwether for the economy.

Wenzhou was one among many hotbeds of private enterprise in China, where success grew from the bottom-up development of family-owned SMEs that perfected the art of low-cost manufacturing for overseas customers. But just as beleaguered exporters in Wenzhou are now staring down the barrel of an uncertain future, questions are now mounting over the role of exports as a driver of Chinese economic growth on a national level, now and in the future.

Trade figures for June added to the anxiety after they came in well below expectations. Exports fell on an annual basis for the first time in 17 months, declining by 3.1% according to customs data from that month. Imports were down 0.6% versus an anticipated 6% rise. In July exports rebounded with a 5.1% rise and again in August with a 7.2% rise, but the sudden fall in June has still left China watchers and China businesses unsteady and considering the best long-term game plan.

The June collapse in trade fanned fears China was headed for a severe slowdown. “If the softness in the trade sector persists, China is unlikely to achieve its trade growth target of 8% for this year,” ANZ bank’s China economists Liu Ligang and Hao Zhou said in a research note in July.

If exports have been China’s bread and butter for decades, what happens to exporters when an economic slowdown coincides with a government-backed campaign to re-balance the economy away from exports and toward domestic consumption?

Factory to the World

In China, missing trade targets would have seemed inconceivable several years ago. Exports have boomed over the past two decades and played an oversized role in Chinese economic stability. The value of exports stood at $91.7 billion in 1993, before more than quadrupling to $440 billion in 2003, according to customs statistics. In the month of December last year alone, export value reached a historic high of $199.2 billion.

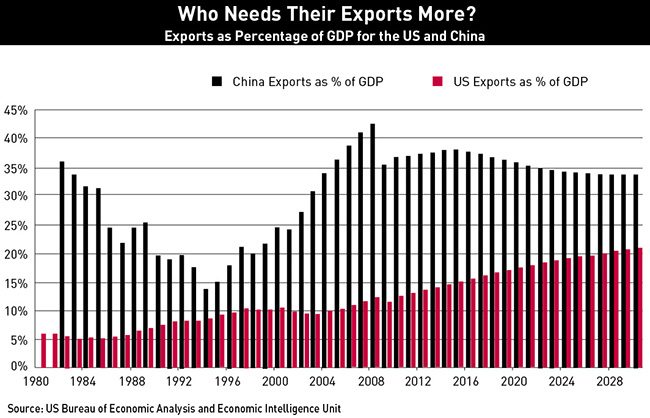

World Bank data shows exports of goods and services represented 11% of China’s GDP in 1980, two years after the country adopted its reform and opening-up policy. That share swelled to 16% a decade later and reached 39% by 2005.

That ratio is very high when judged against developed economies and China’s emerging peers. Exports accounted for just 14% of GDP in the US in 2011, the highest for more than three decades, according to the World Bank. Exports as a share of India’s GDP measured 24% last year, the nation’s highest percentage in more than 30 years. Numerous other countries have higher shares than China—Malaysia’s was 87% last year, for instance—but the GDP for those nations are only a fraction of China’s GDP, and none have had the same impact on global trade in terms of scale.

Beyond the simple fuel that exports have provided to China’s GDP growth are the productivity gains and technological advances made by export-oriented SMEs as they churned out goods to sate foreign demand. Those benefits rippled out to the wider economy as China emerged as the new global factory.

“Foreign demand boosted the manufacturing sector, and that resulted in a very big improvement in productivity,” says Qinwei Wang, a China economist with Capital Economics in London. “That improvement in productivity has been able to spread to other sectors, [and] has been able to help China achieve the fast growth over the past few decades.”

As for the sectors that comprise the majority of China’s exports, manufactured goods were still the leaders at the end of 2011 according to the official statistical yearbook from China’s National Bureau of Statistics. Manufactured goods totalled $17.9 billion in 2011, near all of the total exports of $18.9 billion.

“Chinese firms are shifting their positions upwards,” says Wang. “Before, they used to produce clothing and shoes but now they are starting to produce more electrical equipment—iPads, iPhones. data suggests that the value-added part of the exports is increasing. That’s a big trend, [and] it will continue to increase.”

Within manufactured goods, growth in low-end items like textiles, rubbers and metal products still reigned supreme ringing in at $3.2 billion, an increase of roughly $500 million from the previous year. But growth in higher end manufacturing goods was catching up. Growth in both chemical products—increasing by nearly $300 million from 2010 reaching $1.1 billion in 2011—and in machinery and transport equipment—increasing more than $100 million from 2010, reaching $9 billion—signalled a shift in weight from low-end products to more technically demanding heavy machinery, as experts point out is a result of improvements in productivity and technical expertise.

“Because the market is so competitive, it forces the domestic industry—which otherwise tends to be very protected by access to credit and connections with the government—into innovation, into better research,” says Michael Pettis, Professor of Finance at Peking University’s Guanghua School of Management.

“Without the export sector, I don’t think we could’ve assumed there’d be a lot of upgrading of Chinese manufacturing abilities,” says Pettis.

The surge in exports was felt at China’s ports and reflected in the trade balance. In 2006, Shanghai and Shenzhen were the only two mainland ports to make the global top 10 by container traffic, but they have since been joined by Ningbo-Zhoushan, Guangzhou, Qingdao and Tianjin, according to the World Shipping Council.

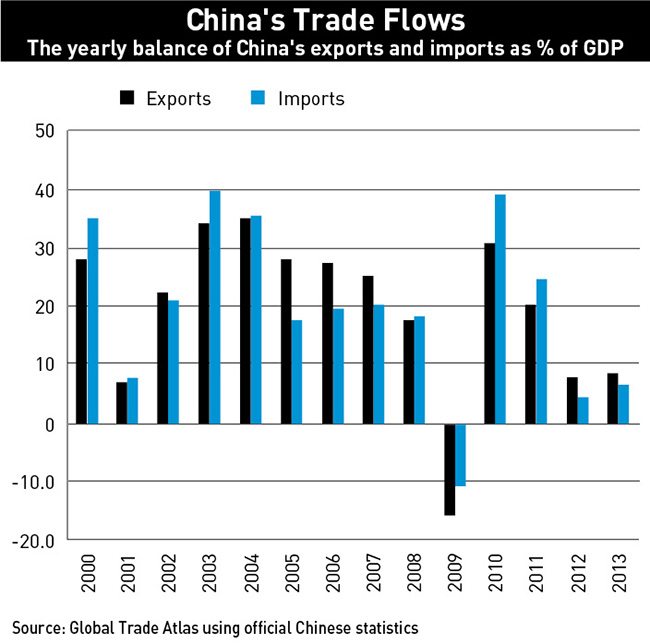

Exports have also charged China’s much discussed trade surplus, which peaked at nearly $300 billion in 2008, according to postings from the central government.

Withering Demand

Now China’s export sector is being buffeted by severe headwinds. “China faces relatively stern challenges in trade currently,” said customs spokesman Zheng Yuesheng after the release of June’s dismal trade figures. “Exports in the third quarter look grim.” Export value between January and March rose 18% from the same period in 2012. Year-on-year second quarter figures, however, show just 3.8% growth.

Wenzhou has been ground zero for this slump in exports. The local economy expanded 6.7% in 2012, more than one percentage point below national growth of 7.8%, government data shows. Last year’s growth was also down significantly from 11% in 2010 and 9.5% in 2011.

The city’s export sector has had little to cheer since Wen Jiabao, then Premier, paid an official visit to local factories in October 2011. Wen pledged financial support to small companies during his visit, which came after a startling number of bankruptcies stemming from a lending crisis. Scores of bosses who were unable to make payments on underground loans fled, with some even taking their own lives.

The desperation has spread beyond Wenzhou. “Last year was the worst year for us. We only exported $2 million, half of what we sold in our best year of 2002,” says a salesperson with an arts and craft maker in Zhuhai, a manufacturing hub bordering Macao and a ferry ride away from Hong Kong.

“Our products are mainly exported to the US and Europe. The economic recession in these places cut our orders by 20-35%,” says the salesperson, who asked not to be named as she was not authorized to speak to media.

Weak demand in developed markets was reflected in June’s trade data, which showed that exports to Europe, the US and Japan fell 8.3%, 5.4% and 5.1%, respectively.

“Foreign demand is not strong and there’s no convincing sign that it’s going to rebound,” says Wang.

The plummeting trade has laid bare the vulnerability of China’s key export industries. The value of Chinese textile and clothing exports rose by 20.1% in 2011 from a year earlier, but that growth rate slumped to just 2.8% in 2012 according to official customs data.

Problems Back Home

As foreign demand began ebbing and a prolonged economic slowdown set in, the Chinese government voiced its intention to rebalance the economy by stoking private consumption in the world’s most populous country. That will be easier said than done. Chinese households have borne the brunt of China’s export and investment-driven growth, according to Pettis. The household sector, he says, has been exploited over the past three decades to support the country’s rapid growth through “hidden transfers” of resources. “You can think of environmental degradation as a transfer. It reduces the cost for companies but it increases the health costs for households,” says Pettis. He singles out the undervalued Chinese currency, low wage growth relative to productivity gains, and low interest rates as the most important of these distortions, as they have effectively underwritten China’s trade boom.

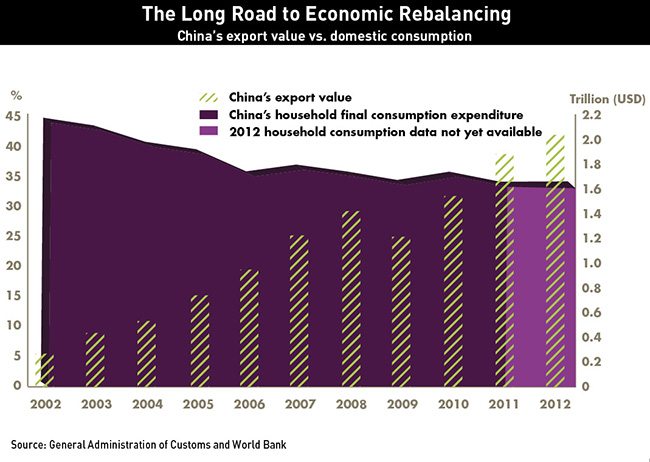

The consequences of China’s export growth at the expense of households can be seen in Chinese household consumption’s share of GDP. Household spending—excluding home purchases—stood at 51% of GDP in 1981, according to the World Bank. It has fallen steadily since then, and averaged 34.5% in the four years from 2008 to 2011.

“The household’s share has dropped and the state’s share has risen. Consumption is driven by households, so if the household’s share dropped, so did the consumption share,” says Pettis. Driving up consumption would involve eliminating the hidden transfers—which have subsidized the growth of China’s export sector—and growing the household share of GDP. That would shrink the Chinese state’s contribution to GDP—a notion that would be fiercely resisted by powerful vested interests.

Beijing’s attempts to engineer an ambitious shift from investment-led growth to a consumption-driven model have also coincided with weak domestic economic performance, either by default or design.

Tepid demand has also set in as the cost of doing business in China rises. The government has embraced higher wages to spur consumer spending, with minimum wages up by 60% since 2009 in spite of the economic slowdown. Research from brokerage CLSA shows nominal manufacturing wages have soared 165% since 2005, while the touted productivity improvements have offset only around 40% of that salary growth. Economists say that relative to manufacturing productivity, Chinese wages are quickly catching up with the US. More expensive labor has fed speculation that manufacturers will seek to ‘reshore’ production in the US, as costs saved by making goods in China evaporate.

“Many people are worried about the outlook of China’s exports. One argument is that the fast growth of wages will damage the competitiveness of export firms. [But] Chinese firms can still leverage the improvements in productivity to offset the increase of wages,” says Wang.

Along with rising labor costs, recent appreciation in the renminbi has also taken its toll on exporters. China’s currency has gone from being controversially weak to uncomfortably strong, strengthening against the US dollar by about 5% annually since Beijing reformed exchange rates in 2005. So far this year, the renminbi has gained around 1.5% against the dollar, more than last year in total.

Government to the Rescue?

The alarming slowdown in June’s exports fanned speculation that Chinese policymakers would offer some help to ailing exporters. While China’s leadership has firmly ruled out a large-scale fiscal stimulus, Beijing did announce supportive measures at the end of July for exporters. These included streamlined customs procedures, fee cuts and tax exemptions.

“It’s moving things in the wrong direction because if [the central government] cuts taxes, then it’s going to have to turn somewhere else for those tax revenues. And the typical somewhere else is the household sector. It has the same impact as depreciating the currency—it basically forces up exports at the expense of the household sector,” says Pettis.

As Pettis notes, there is a disconnect between the public campaign for consumption growth and the measures policymakers are actually taking, which means exporters may not have to contend with a full-on economic shift for quite some time. But certain government stances on economic transition are unavoidable, particularly when treading currency valuation, which would be the quickest way to boost exporters.

A spate of large companies failing due to a stumbling export sector could see Beijing spring into further action, to stave off a potentially destabilizing round of mass layoffs. But devaluing the currency to improve the price of Chinese goods sold abroad is likely not in the cards, according to Pettis and Wang.

“The reason I never believe [currency depreciation] would happen is because that means instead of rebalancing the economy, China is taking steps to make the imbalances worse. Remember, the heart of the imbalances are very low interest rates, low wage growth and an undervalued currency,” says Pettis.

Stabilising the currency, rather than devaluation, may be fair game according to economists with foreign banks. “The renminbi has appreciated too quickly… and negatively affected export growth,” said Ma Jun, Deutsche Bank’s Chief Economist for Greater China, in a July research report. “We believe that the People’s Bank of China will be instructed to keep the renminbi more stable in H2 [second half].”

The prospects for China’s export machine will hinge upon the rest of the world, with the US playing the dominant role, says Pettis. “The US is starting to recover. Europe isn’t. I don’t think Japan is going to be a lot of help for the next few years. It really depends on the US recovery, and the US recovery is happening but it’s weak, so I think [exports] could easily be derailed by trade actions of other countries.”

Exporters and manufacturers are also taking action to insulate themselves against further losses. Besides the switch to higher-value exports in the form of machine tools or electrical and electronics systems, Chinese firms are shifting low-end production to either other regions in Southeast Asia, or China’s hinterland, to take advantage of cheaper labor. “It makes you more competitive and also profit margins are higher,” says Wang. “Also China is moving some production from the coastal area to the hinterland, where they have cheaper labour. And those laborers in the coastal areas are more productive, so they can be used for other high-end production.”

The country is likely to downsize, not abandon, its role as factory to the world. “Chinese firms are still holding up,” says Wang. “The bigger picture is that China’s exports sector is experiencing adjustment, but not in a worrying way. Export growth is going to be in line with economic growth or slightly under.”

But such optimism is in short supply in the quiet workshops of Wenzhou. “Our rising labor costs and the yuan’s appreciation have squeezed our meagre profits,” says Yang from Yongli Suitcase.

“However, we have to make the products for our customers. We have to pay our debts. We hope things will be better in the future.”