Diverging Paths

China and India have shown solid growth in recent decades, but the other BRICS countries have not fared as well

At first glance, the BRICS organization seems like an odd group: five clearly disparate countries bundled together. But when economist Jim O’Neill coined the acronym BRIC two decades ago, he was looking at one clear commonality: Brazil, Russia, India and China were the world’s largest emerging markets. Back then in 2001, O’Neill boldly predicted that the grouping would overtake the six largest Western economies by 2050.

We are now almost halfway through that 50-year period and the world has changed drastically since those nations were first grouped together. For starters, they have a new member: South Africa officially joined the BRIC grouping (henceforth known as BRICS) in 2011. The context has changed as well: there have been global economic crises, political upheavals, a global pandemic and even a war waged by a key BRICS member. So how credible is O’Neill’s hypothesis at this point? Today, most people, including O’Neill himself, consider it to be at best a tall order.

“Much has happened in the two decades since the BRICs became a group to watch in the twenty-first century,” O’Neill wrote in 2021. “While some of them have surpassed expectations, others have fallen short, as have the relevant global-governance institutions.”

“From an investment perspective, BRICS made sense when it was formed,” says Mandira Bagwandeen, senior research fellow at The Nelson Mandela School of Public Governance, University of Cape Town. “But today, it’s unlikely that all five countries will get to where O’Neill had in mind.”

Foundational blueprint

The BRIC concept, originally formulated by O’Neill in a Goldman Sachs study in 2001, quickly became an analytical category that was most successfully used as a marketing tool for investors and as a basis for a number of funds and stock indices. At the time, the four countries represented a combined 8% share of world GDP, and the expectation was then that, in the coming decades, China would become the world’s factory, Brazil its food supplier, India its service provider and Russia its gas station. That’s not exactly how things played out, but nevertheless the countries together now account for around a quarter of global GDP.

The BRIC foreign ministers first met in 2006, and the first official summit was held three years later in Russia, where ambitious plans were unveiled. As a result, BRIC became something more than just a concept for the financial markets and an official organization was established, which is now headquartered in Shanghai.

“What transformed the BRIC concept from an investment thesis was the global financial crisis of 2008-2009,” says Zongyuan Zoe Liu, a fellow for international political economy at the Council on Foreign Relations in New York. “During this crisis, people started questioning the Western-led financial system because it was collapsing. BRIC stood for an alternative to the Western hegemony.”

South Africa was formally invited to join the bloc in 2011, transforming it into BRICS. At the time, the country had the largest economy in Sub-Saharan Africa, accounting for about a third of the region’s GDP, and its inclusion was intended to make the whole group more credible as a representative of the Global South.

Today, according to World Bank figures, the BRICS nations have a combined GDP of more than $24.7 trillion, around a quarter of the global total of $95 trillion. The five countries also represent 40% of the world’s population, dwarfing the G7 countries—the world’s most advanced economies—which make up only 10% of the global population.

Officially, the primary purpose of the BRICS organization is to broaden cooperation among members and enhance support for a multipolar world order. But due to the geographical disconnect, economies being at different stages of development, and a fair degree of ideological dissonance, things have not worked out as originally predicted.

“BRICS is really a loose semi-institutionalized, semi-partnership grouping,” says Liu. “People can put forward all kinds of agendas. No country is dominating the conversation. So, from that perspective, it is very different from the US’ financial system. Essentially, every country has veto power.”

But the group has been able to chalk up some accomplishments in the past two decades, the most notable of which is the establishment of the BRICS bank, called the New Development Bank (NDB), which lends money for infrastructure and other projects aimed at boosting growth.

The NDB has an initial authorized capital of $100 billion, which is divided into one million shares. The five BRICS nations initially subscribed 100,000 shares each, which endowed the bank with an initial $50 billion in capital. The remaining shares are either still unallocated or have been opened up to other countries, including Bangladesh which has 9,420 shares and the United Arab Emirates with 5,560 shares.

Since its founding, the NDB has signed more than 30 strategic partnership agreements with other international and national financial institutions and approved nearly $32 billion in loans to support over 90 infrastructure and sustainable development projects. It has since committed to lending a further $30 billion over the five-year period between 2022-2026 while also extending financing in local currencies by 30% as it attempts to shift further away from the US dollar.

The NDB’s portfolio features investments in areas such as clean energy, urban mobility, water, sanitation, transport and, social and digital infrastructure, which aligns with the goals of China’s Belt and Road Initiative of creating sustainable development projects.

Critics have highlighted the imbalanced weight and influence that China has in the bank, with the NDB’s headquarters located in Shanghai, Chinese credit rating agencies being the first to give the bank high ratings for its activities and the China Interbond Market issuing most of the bonds the bank has agreed to.

Another downside is that due to its limited membership, it has access to less funding than other similar multilateral development banks. Credit terms are also unclear, with ministries in Bangladesh appearing uninterested in a $5 billion loan from the bank, claiming that they are unaware of credit terms. Economists have been pushing for setting the scope of loans first, as it is said that loans are becoming more expensive.

“BRICS is a pragmatic group,” says Jinghan Zeng, Professor of China and International Studies at Lancaster University. “But that pragmatism doesn’t mean that BRICS is going to be the IMF. It’s about broadening their voice through their own institution while also using their institution to pressure existing institutions to change.”

A good start

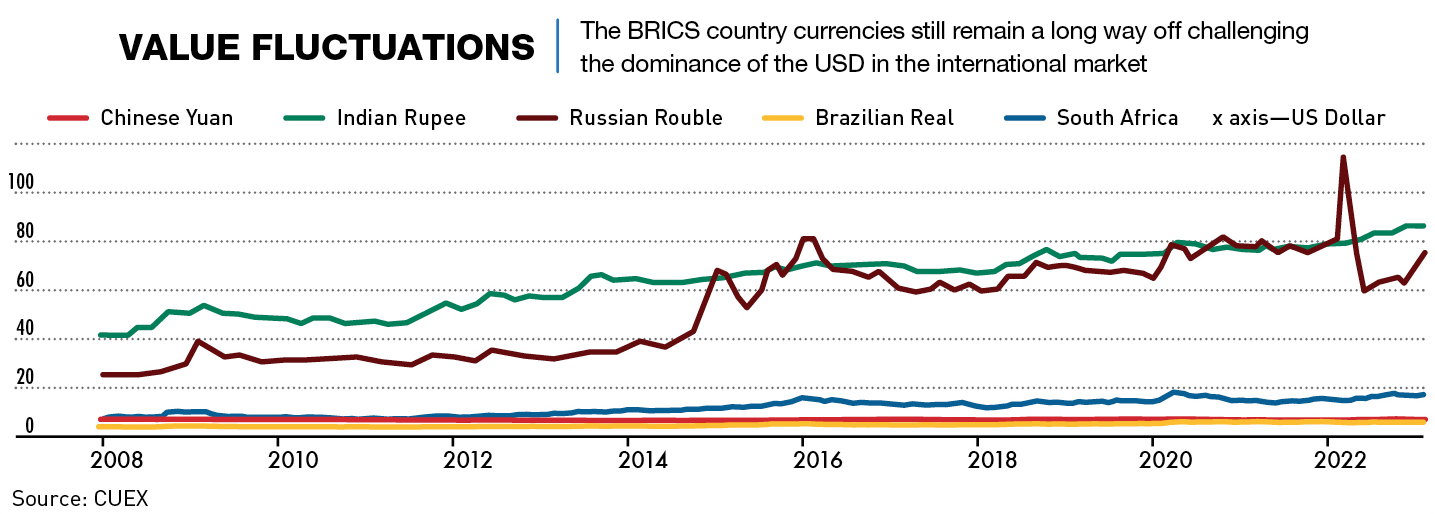

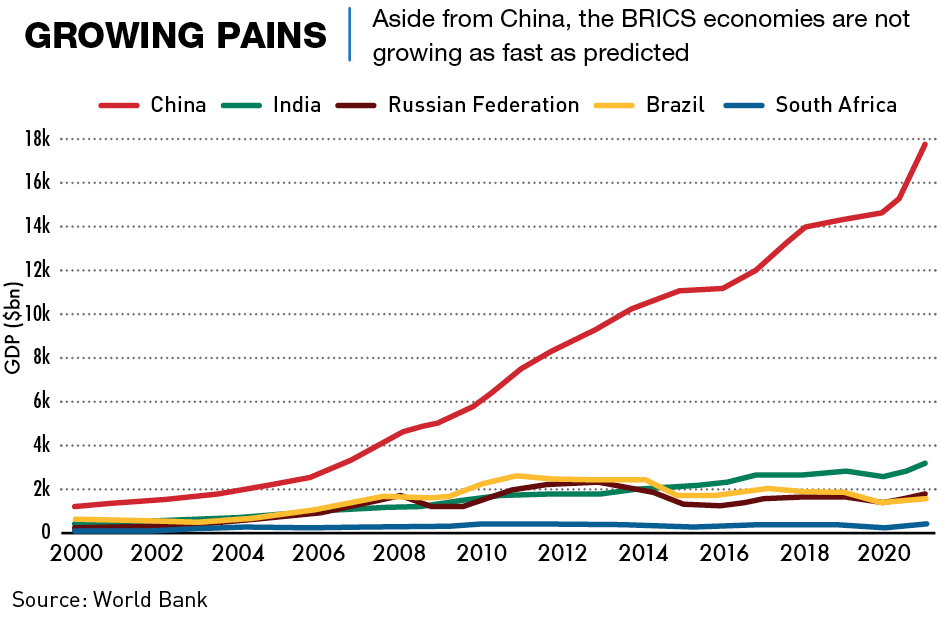

The BRICS countries emerged from the 2008-2009 financial crisis relatively unscathed, but aspirations of catching up with the West were set back by the commodity crash of 2014. And while collectively BRICS has moved back into growth territory, contributions from the constituents have been very uneven.

World Bank data has shown that Brazil, Russia and South Africa’s share of global GDP has shrunk since 2000, dropping to a combined 2.98% down from 3.16%. While at the same time, China and India’s share of the global economy as a whole has grown to 5.43%, up from 4.94% in 2001.

“The idea’s inception was based on the fact that these economies were clustered together because of their growth potential,” says Mihaela Papa, Adjunct Assistant Professor in Sustainable Development and Global Governance at Tufts University. “Yet when we look at the past two decades, their individual growth trajectories varied, especially in the last decade.”

Brazil, which had been experiencing robust growth, suddenly entered a recession in 2014 from which it is yet to emerge. Its manufacturing base has shrunk but services industries have not developed enough to achieve the levels of growth expected by O’Neill in 2001.

Russia meanwhile, formerly a superpower in its own right, has seen its economy plateau and decline, particularly since its 2014 annexation of Crimea, and compounded by the major shock of the Ukraine war and the sanctions that accompanied it. Prior to the conflict, the country’s GDP was just half the size of the state of California, despite being the most resource-rich state on earth.

South Africa, whose economy is handcuffed to the world’s commodity markets, has for years suffered from high unemployment, endemic inequality and massive corruption.

India has seen tremendous growth over the two decades, with a surge in foreign direct investment and a more commercially-minded government under Prime Minister Narendra Modi, but its economy today is still just one-fifth the size of China’s.

China, on the other hand, as the second-largest economy in the world, the largest consumer of energy and minerals, and the largest exporter of goods and services, has seen such consistent growth that it has actually changed the way that economic power is distributed globally. Its 2022 GDP of $18.32 trillion is more than double that of all the other four BRICS combined.

“You could go as far as to say that China alone is BRICS,” says Bagwandeen. “Brazil, Russia and South Africa’s growth rates have not fared very well over the years, and the other BRICS economies are significantly dwarfed by China.”

Relationship goals

China’s massive rise has also impacted the relationship between all the BRICS members. “Not every BRICS country benefited equally from the grouping,” says Liu. “Essentially, China can be without BRICS if it comes down to it, but BRICS cannot be without China, and this fundamentally affects the relationships between the countries. BRICS has also seen damage to its reputation because of Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, making Russia more of a liability to the group right now.”

“None of the BRICS members have openly criticized China or Russia over US-China tensions or the Russia-Ukraine war,” says Bagwandeen. “Brazil, India and South Africa have to play a very careful balancing act. China and Russia are valued political and economic partners, especially in the Global South, so they wouldn’t want to rub them the wrong way.”

Longer-term challenges remain, including the volatility of commodities markets and the world economy, the economic impact of climate change and environmental degradation, an aging population in the case of China and coming to terms with the implications of digitalization. How they react to these challenges will determine how each of these players will fare in the lead-up to O’Neill’s 2050 target.

“Major long-term economic development challenges for all BRICS countries include managing and adapting to climate change and being proactive about the AI revolution and its impact on trade flows and labor,” says Papa. “What we need to examine is whether these countries are making investments that can help them operate in a world facing climate stress and the Fourth Industrial Revolution.”

“Having massive populations and cheap labor used to be an advantage for these countries,” says Liu. “But they are slowly losing that advantage.”

While the fate of the five players diverged in ways which were never predicted, the BRICS as a concept and as an organization has still managed to stay together with an interlinked financial infrastructure that provides cohesion and value to some extent.

This includes the Contingent Reserve Arrangement, which can provide liquidity for member countries in times of economic crises, and individual alternatives to the SWIFT system. These tools have, to some extent, offered a safety net for Russia—after being kicked out of the SWIFT system in February 2022—and China, with Chinese entities being at increased risk of being sanctioned as part of the US-China decoupling process.

The New Development Bank, and the over $30 billion that it has already lent, has also been crucial in supporting infrastructure and sustainable development projects in BRICS and other developing countries. There are a large number of important clean energy, urban mobility and transport projects that would not have been possible without NDB funding.

“Those are indeed emerging markets’ attempts at establishing their own alternative financial governance body, as an alternative to the existing legacy institutions like the World Bank and IMF,” says Liu. “For a country to raise capital in the international market, you have to be evaluated based on sovereign risk and customer credit rating. So if you don’t necessarily have a good credit rating, in many ways, you cannot raise funds cheaply, or at all.”

Future expansion

At the 2022 BRICS summit hosted in Beijing, China’s leader Xi Jinping compared the BRICS economic bloc to a “giant ship” sailing forward “against raging torrents and storms.” But huge disparities in the economic might of BRICS members and their deep differences on various issues have raised questions about the accuracy of this metaphor.

Russia and India characterize themselves as allies in many ways, and Russia also has a comprehensive partnership and strategic cooperation with China, a major rival to India. India has long regarded China as a threat, and the two countries have occasionally been embroiled in border skirmishes. China is viewed as being fundamentally supportive of Russia, despite the invasion of Ukraine presenting a problem for its partners in many contexts, including BRICS.

Brazil and South Africa, on the other hand, are leading powers in their own regions. Moreover, despite disagreements, it is highly unlikely that Brazil will leave the BRICS group, as the country is highly dependent on Chinese imports and therefore needs to maintain good relations with Beijing.

“Geopolitical tensions have had a dual effect,” says Papa. “On one hand, they increased distrust among BRICS, and now it is less clear what BRICS stands for. On the other hand, they have led to broader realignments around BRICS in contemporary politics. BRICS has candidate countries and needs to decide how—and whether—it makes sense to scale its operations and what kind of members would be a good fit.”

Since 2013, non-BRICS countries have been invited to attend the annual summit,

and, in 2017, China proposed a “BRICS Plus” framework, naming countries like Indonesia as potential new members. Other countries that have expressed interest in joining an expanded BRICS-plus framework include Nigeria, the United Arab Emirates, Saudi Arabia, Kazakhstan and Thailand.

“A lot of people think that countries like Indonesia would make a good addition,” says Zeng. “But adding countries to BRICS needs to be considered carefully to avoid what happened when the idea was created. It did not have a methodologically sound approach to explain why some countries were included and others not. BRICS also represented a phenomenon that today isn’t as significant as it was before.”

“When we are looking at these countries that want to join BRICS, they are also not on an equal playing field at all, just like the original BRICS countries,” says Liu. “These countries wanting to join shows that they have a hedging strategy in mind; they need an insurance policy against things like Western sanctions.”

Alternative options

For other emerging countries looking to join international groupings, there are alternatives to BRICS including other inter- and intra-regional alliances such as the MIKTA—an informal partnership between Mexico, Indonesia, South Korea, Turkey and Australia created in 2013—IBSA—India, Brazil and South Africa—and the Shanghai Cooperation Organization (SCO).

“The formation of informal groups is now a common way of doing business beyond the state level, so we are likely to see more of such groups in global governance,” says Papa. “Since the BRICS countries are divided on security issues, other groups like IBSA may become more appealing to these countries.”

The SCO, for instance, is a Eurasian political, economic and security forum founded in 2001 that is now comprised of nine member states: China, India, Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, Russia, Tajikistan, Pakistan, Uzbekistan and Iran.

“The SCO follows the old idea of having a group of countries which agree with each other and support each other,” says Zeng. “But I don’t think organizations like this will work in the future. Of course, we need geopolitically-based organizations like the SCO, but can they evolve into something like BRICS? Or will they become something different? It is still too early to tell.”

MIKTA is a grouping of foreign ministers of the member countries and aims to support effective global governance. IBSA is a forum, formalized in 2003, used as a platform for its three members to discuss political and economic issues.

“Other than BRICS, there are no significant groupings that really stand out,” says Bagwandeen. “There were talks of MIKTA in 2013, but when you look at the group’s makeup, they will more often than not dovetail and support the G7 when it comes to voting on problematic issues. BRICS can be considered the multilateral muscle of the developing world.”

Whether these alliances can replace the role that BRICS plays depends on whether they can find a way to effectively address common issues faced by the countries.

“It depends on how the world’s political landscape might eventually evolve,” says Zeng. “When it comes to climate change, for example, China and India support each other. But when it comes to other issues, they don’t. So instead of moving from a bipolar world to a multipolar world, you see an issue-based world order. It is different from how we understand the world now.”

Increasing insulation

Some analysts argue that BRICS members likely realize the group is a limited-purpose partnership, in which political barriers will always get in the way of it reaching its full economic potential, but still feel it has value, albeit in a limited way. Globalization on the wane, each BRICS member nation prefers to pursue its own geopolitical and economic interests.

Long-term, there is potential to step up economic growth and trade between the member countries by intensifying their integration. In the meantime, BRICS will likely continue to be a group of emerging nations that exists to discuss global issues of mutual interest.

“Over the next 10 years, volatility will be high,” says Liu. “I think this will not necessarily be driven by economic and financial markets but by geopolitics. So I would advise my clients or investors looking into BRICS countries to be cautious in terms of pricing.”

“BRICS will still exist in 2050, but how much weight and power it has to influence the global political and economic system is the question,” says Bagwandeen.

“Not every country in BRICS is going to achieve what Jim O’Neill had in mind,” says Zeng. “But some of them still have considerable potential, like India and China. So we cannot say that O’Neill’s hypothesis was wrong, but you can see that some countries are on track to achieving the original goal while others are not.”