Cities across China are pouring investments into research and development in a bid to transform themselves into world-class innovation hubs. An “innovation race” is heating up among China’s leading cities, particularly in the Pearl River Delta. Some smaller players are also trying hard to catch up. Will they be able to compete with the likes of Shanghai and Shenzhen?

Cities across China are pouring investments into research and development in a bid to transform themselves into world-class innovation hubs. An “innovation race” is heating up among China’s leading cities, particularly in the Pearl River Delta. Some smaller players are also trying hard to catch up. Will they be able to compete with the likes of Shanghai and Shenzhen?

The news surprised no one, but when the Hong Kong government confirmed on March 1 that Shenzhen, the city next door, had overtaken the former British colony to become the largest city economy in south China, the shock still resonated strongly. After all, only 40 years ago, Shenzhen didn’t exist.

Now, the startup city has a population of 15 million, more than double that of Hong Kong. The gross domestic product (GDP) of Shenzhen reached $355 billion in 2017, compared to Hong Kong’s $340 billion. Many in Hong Kong saw the milestone as confirmation that their city was falling behind its dynamic rivals across the Chinese mainland border, and there have been urgent calls for action to keep up.

Hong Kong’s Financial Secretary Paul Chan has unveiled sweeping reforms to the city’s budget, including a 13.5% year-on-year increase in expenditure and a 500% rise in the amount of funding set aside for promoting innovation. For the traditionally laissez-faire Hong Kong government, the changes represent a striking shift in approach toward state interventionism. In his budget speech, Chan justified the switch in stark terms.

“To shine in the fierce innovation and technology race amidst keen competition, Hong Kong must optimize its resources by focusing on developing its areas of strength,” he said.

In doing so, Hong Kong is tacitly paying tribute to the extraordinary success achieved by its neighbors in the Pearl River Delta. Formerly famous for cheap, low-end manufacturing, cities such as Shenzhen and Guangzhou have reinvented themselves over the past decade to become globally-competitive innovation hubs.

Shenzhen in particular is gaining a reputation as China’s answer to Silicon Valley, home to a dynamic startup scene as well as world-leading tech companies including content and social media giant Tencent, telecommunications group Huawei and drone maker DJI. Together, Shenzhen-based companies accounted for over half the patents filed nationally in China in the first half of 2016.

According to Chen Xiangming, Director of the Center for Urban and Global Studies at Trinity College in Hartford, Connecticut, the key to Shenzhen’s transformation has been aggressive promotion of high-tech industries.

“What Shenzhen has done is single-mindedly focus on doing one thing better than anybody else, and that’s innovation,” Chen tells CKGSB Knowledge. “It has very strong supportive policies for research and development.”

Hong Kong is far from alone in attempting to learn from Shenzhen. As Chan suggested in his speech, cities across China are now aggressively promoting R&D in an attempt to shift their economies toward an innovation-led growth model.

“Senior government officials eventually figured out that [Shenzhen’s] mysterious weapon is innovation,” says Lin Jiang, Professor of Economics at Sun Yat-sen University. “The cities’ competition might end up being based on innovation: how much they’re expending on R&D.”

For decades, the fierce competition among China’s cities—which many consider a key force driving the country’s fast economic growth—has focused mainly on large-scale fixed-asset investment. A shift toward competing on innovation is likely to have far-reaching consequences. Which cities will emerge as the winners and losers from this new struggle, however, is far from certain.

The Magic Solution

For cities on the Chinese mainland, the shift toward promoting high-tech industries is largely born of necessity. As Jeongmin Seong, Senior Fellow at the McKinsey Global Institute, explains, the twin engines that have driven much of China’s economic growth over the past decades—a huge demographic dividend and fixed asset investment on a vast scale—are gradually losing steam.

“China’s working age population started declining in 2012,” explains Seong. “Meanwhile, the return on [fixed asset] investment—the capital efficiency—is declining as China’s economy matures. At the same time debt levels are rising. The debt-to-GDP ratio has been soaring, especially since the 2007 global financial crisis.”

He adds, “So, China needs a new engine, which they believe is innovation.”

China’s top leaders have placed increasing emphasis on promoting high-tech industries in recent years. President Xi Jinping calling innovation “the primary force driving development” in his landmark address at the 19th National Congress of the Chinese Communist Party in October. As a result, municipal officials in almost every Chinese city are under pressure to promote innovation, according to Lin.

“The State Leader has stressed the all-importance of R&D, innovation and making China more creative,” Lin says. “The lower-level governments have no choice but to follow what the State Leader said.”

An additional factor driving Chinese cities to implement pro-innovation policies, Lin explains, is the tough competition for promotion that exists among Chinese government officials of the same rank: local officials are keen to impress their superiors by out doing their peers.

These competitive pressures have been effective in driving officials to achieve fast economic growth in the past, and it may help accelerate China’s emergence as a high-tech power. “Cities are competing. And that’s a good competition, because innovation and competition go hand in hand,” Seong says.

However, Lin argues that these political forces are also creating problems in some cities, because officials are too eager to achieve fast results. This is leading them to grasp for a simple, magic solution, which in many cases is pumping government money into research and development.

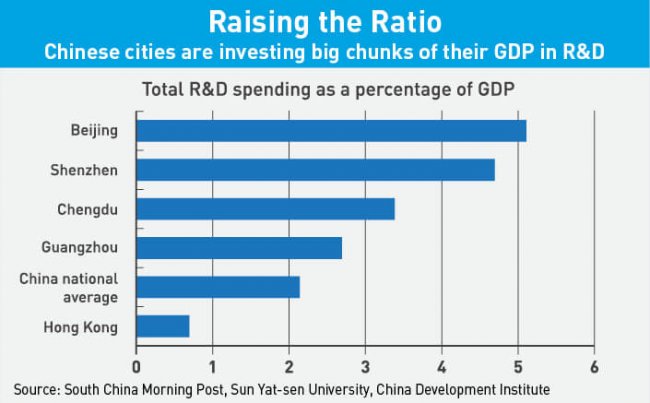

Governments across China have latched onto the fact that Shenzhen invests a whopping 4.7% of its GDP in R&D. This is an even higher percentage than world-leading high-tech powers Japan, Israel and South Korea, and far beyond the 0.7% of GDP that Hong Kong invests. Many cities have recently announced plans to raise their R&D to GDP ratio. Guangzhou has set a target of hitting a 2.7% ratio. Chengdu’s figure has already leaped above 3%, while Beijing’s has reached 5%. Carrie Lam, Hong Kong’s Chief Executive, also plans to double the Special Administrative Region’s ratio to 1.5% within five years.

“[City] government leaders believe that if they have the same [R&D ratio] figure as Shenzhen, they may achieve the same results. They sincerely believe that,” says Lin. “But they ignore what the real situation is: Shenzhen’s success is due to other economic factors.”

A Long-term Project

As Guo Wanda, Executive Vice President of the China Development Institute, points out, Shenzhen’s much-hyped 4.7% ratio is a symptom of success, rather than its cause.

“Shenzhen is different to Beijing and other cities like Shanghai because most of the R&D spending comes from private companies,” says Guo. “More than 90% comes from enterprises, especially private companies.”

This is not to say that the Shenzhen government has not played an important role in the city’s emergence as a tech hub. Local officials have been laser-focused on promoting innovation since at least 2000, using a mix of regulations and incentives to move out low-end manufacturers and replace them with high-tech startups. Crucially, it has not let the state crowd out the private sector.

The government has played more of a facilitator role, creating the right environment and incentives to encourage companies to innovate, as well as fair competition and attractive R&D subsidies. The city also has stronger intellectual property and contract protections than elsewhere in China. This has given Shenzhen’s private companies the security to invest big in innovation: more than 40% of DJI’s employees work in R&D. At Huawei and Tencent, the figure is over 50%.

Creating this kind of innovation-friendly ecosystem takes time, Guo emphasizes. “[The Shenzhen government’s] recent policies are not so important—it’s more an accumulation of innovation,” he says. “For example, Huawei was set up in the late 1980s.”

For Professor Lin, this offers an important lesson for other Chinese cities about the importance of allowing the market to play the decisive role in driving the allocation of R&D resources.

“A high [R&D to GDP] ratio may not necessarily mean high economic efficiency,” he warns. “For example, Guangzhou has an efficient market in comparison to Chengdu. If the Guangzhou government spends RMB 10 million, it may generate the equivalent of RMB 20 million in terms of the output of R&D in Chengdu.”

If local governments simply pump money into state-run projects, there is a risk that they “may crowd out some private sector investment,” says Lin. “Some companies may think, ‘the government is spending money [on R&D], why should I continue to spend money? I can just be a free rider.’”

Ten Shenzhens

According to Chen from Trinity College, Shenzhen may be an unsuitable model for other cities to follow in other ways, too.

“I’ve heard people say, ‘If China could create 10 Shenzhens, then China would be even more powerful,’” he says. “But that is an idealistic way of thinking. The circumstances, the coming-together that favored Shenzhen in such a unique way cannot be replicated elsewhere.”

For starters, there is Shenzhen’s status as a “miracle city” that was created by a stroke of a pen by former Chinese leader Deng Xiaoping in 1978. According to Chen, this not only ensured that the city government was “not polluted by the inefficiencies of the old centrally-planned economy”; it also helped create an open and diverse society in which 99.9% of the population is made up of migrants—the perfect breeding ground for an innovation hub.

“These arrivals were highly educated, highly entrepreneurial and highly risk-taking,” says Chen. “They went to Shenzhen to seek out new opportunities.”

Another advantage has been Shenzhen’s proximity to Hong Kong, which sits just across the Sham Chun River. “The Shenzhen officials took advantage of Hong Kong’s resources,” explains Lin. “Hong Kong’s financial circle wanted to help Shenzhen develop a high-tech center, because this is not a strength of Hong Kong.”

There has also been a certain amount of serendipity behind Shenzhen’s rise. In the 1990s, the city’s strategy was to compete directly against Hong Kong’s shipping and finance companies, according to Lin. But this plan was foiled by a deal struck between Hong Kong and Beijing soon after the city’s return to China, which forbade Shenzhen from undercutting Hong Kong’s core industries.

The upshot was that instead of seeking to attract banks, Shenzhen chose to focus on luring venture capital funds. More than 500 VC firms are now based in the city, and they have played a hugely important role in developing its innovation ecosystem.

“The venture capital funds not only provided Shenzhen’s firms with capital; they also provided the entrepreneurship and supply chain management skills—the professional expertise that Shenzhen’s business firms needed,” says Lin.

Taking a Different Road

However, this does not mean that cities cannot succeed without the advantages enjoyed by Shenzhen. Chen points to the example of Guangzhou, just 140 kilometers northwest of Shenzhen.

As the provincial capital of Guangdong Province, Guangzhou has not been allowed Shenzhen’s relative freedom from bureaucratic oversight; nor has it benefited from a mass influx of budding entrepreneurs. But the city has been able to leverage its elite universities and research institutes to support a number of emerging industries, such as biotechnology and new materials. This helped Guangzhou achieve GDP growth of 7% in 2017, not far off Shenzhen’s 8.8%.

“Guangzhou’s educational resources and research capacity have allowed it to do fairly well—not as well as Shenzhen, but certainly better than any of the other cities in Guangdong—in becoming more innovative and competitive,” says Chen.

Smaller cities without the local talent pool provided by top-class universities, however, will often gain little from investing large government resources in R&D. “If you buy expensive R&D equipment and you don’t know how to use it, then you will hit that R&D investment target, but… there will be waste,” points out McKinsey’s Seong.

Lin suspects that in some cases, local officials may simply be investing for political reasons. “How can they show they are responding to the top leaders’ requirements [to promote innovation]? The only figure is the R&D ratio,” he says.

Some analysts worry that in China’s new era of innovation-led growth, less fashionable cities will find it even more difficult to compete with first-tier metropolises like Shenzhen and Shanghai, which tend to hoover up the best talent.

“When cities become big and become a magnet for talent, and also attract different groups of people like investors, entrepreneurs, marketing and manufacturing companies, there is a better chance for this city to become a big innovation hub,” says Seong.

Hooking a Big Fish

Instead, smaller cities may need to try a different approach to jump-start their development. One possible option is the route taken by Hangzhou, the capital of Zhejiang Province on China’s east coast. Not long ago, Hangzhou was known as a picturesque but run-of-the-mill Chinese city.

Today, it is famous as one of the country’s leading centers of innovation, often placed just below Shenzhen on the pecking order of China’s leading tech hubs. The rapid rise of Hangzhou can be explained in one word: Alibaba.

China’s biggest tech company was originally based in Shanghai, but in the late 1990s Hangzhou was able to convince the company’s chairman, Jack Ma, to relocate. The key attraction of moving out of Shanghai for Ma, explains Lin, was that his company would be a big fish in a small pond: the local government would go out of its way to make sure that the company was able to secure access to bank loans and other means of support.

“Hangzhou’s officials made a good choice, because Hangzhou at that time had no more financial or technological resources than any other provincial city,” says Lin. “Alibaba’s arrival provided Hangzhou with good opportunities.”

Over the past decade, an entire e-commerce ecosystem has developed around Alibaba in Hangzhou, which has also driven the development of related industries like cloud computing. Hangzhou also benefits from the fact that it is a quieter, pleasanter place to live than many Chinese megacities.

“Hangzhou is a clean city with beautiful scenery, a bit like the [San Francisco] Bay Area in the United States,” says Lin.

Growing Together

Ultimately, however, China Development Institute’s Guo believes that smaller cities should not look to beat tier-one tech hubs, but rather feed off their success. If towns are well-connected to a major city, for example, it is easier for them to attract high-level talent.

Seong seconds this point. “Cities can compete with each other, but they can also complement each other,” he says.

The Chinese government aims to support this by connecting Beijing and Shanghai with the towns and cities surrounding them, as well as creating a Pearl River Delta Greater Bay Area. This will link together south China’s major cities—including Hong Kong, Guangzhou and Shenzhen.

According to Guo, these projects could make a big difference to a lot of China’s less fashionable cities. “Cities should be connected to each other,” he says. “The central government should have an ambitious strategy about regional integration.”

The Greater Bay Area could even offer a possible solution to Hong Kong’s innovation woes. The city has struggled to promote innovation in part because it offshored its industrial base to the mainland during the 1990s and 2000s.

“The people in Hong Kong feel that they’re playing catch-up in trying to redevelop their capacity to innovate,” Chen says. “But it’s difficult to do it because Hong Kong no longer has that strong manufacturing base—that foundation that Shenzhen has built up and is able to sustain.”

However, new transport links such as the Guangzhou-Shenzhen-Hong Kong high-speed railway and the Hong Kong-Macau-Zhuhai Bridge are eroding the barriers between Hong Kong and its neighbors on the mainland. The new railway will run from central Hong Kong to Shenzhen’s Futian business district in just 20 minutes.

With its deep reserves of talent and business know-how, Hong Kong may find a new role: not as a competitor to the PRD’s other great cities, but as the nerve center of this emerging new mega-region, which looks set to become one of the centers of the global tech industry.