China’s national sportswear champion, Anta, has set its sights on becoming the country’s new market leader. Will it be able to knock out the likes of Nike and Adidas to reach its goal?

Anta, the leading Chinese sportswear brand, is determined to make itself as well-known and trendy around the world as Adidas and Nike. With it being named an official sponsor of the 2022 Beijing Winter Olympics and President Xi Jinping having been seen wearing the brand, it might be a race it stands a chance of eventually winning.

In the Anta store on Shanghai’s renowned Nanjing East Road, sales personnel proudly stress Anta’s position as the number one Chinese sportswear brand and pitch their bestselling footwear, a lightweight and low-price sneaker for RMB 369 ($52).

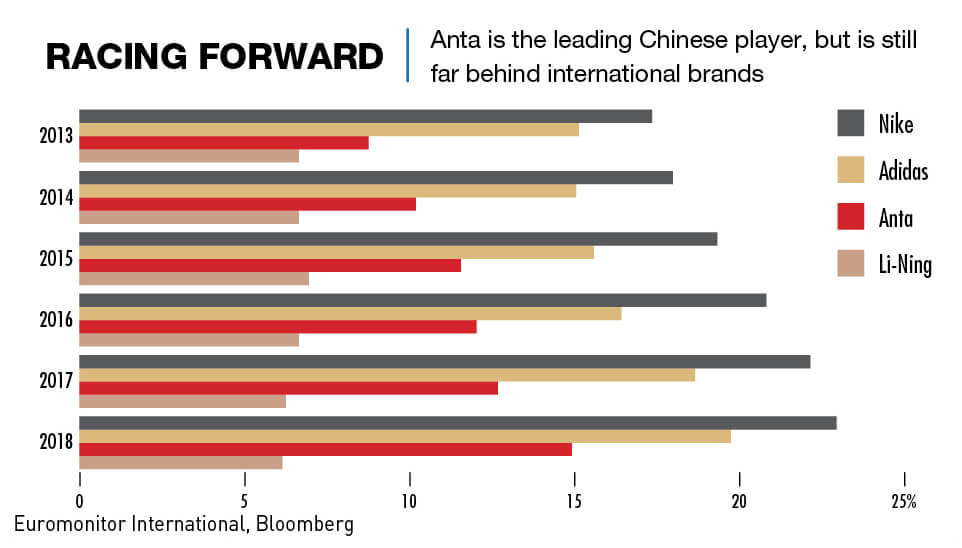

Anta has a 15% share of China’s sportswear market, but it is still behind the top global brands: Adidas has 20% and Nike 23%. “During the past November 11 shopping carnival [similar to Black Friday in the United States], Anta achieved RMB 1.83 billion ($261 million) in sales, with 63% growth year-on-year,” says Karen Dai, group project director at ISPO, a society that organizes a leading sports fair in Munich each year. “Anta listed number three in the sports category and their kids’ line listed number four in that segment.”

Anta’s game plan is to use the 2022 Winter Olympics to vault over Adidas and Nike to become number one in sportswear in China, a market which is currently worth $43 billion annually, but the company still faces a problem with market differentiation. “Domestically their brand has been well-received over the last decade or so,” says Mark Thomas, managing director at sports marketing company S2M Group. “They are in a fairly positive position, but are their products any different to Adidas and Nike?”

On your marks

Anta is a relatively young player in the global sportswear scene. It was established by company chairman Ding Shizhong in Fujian Province in the south of China in 1991. The last few years have seen rapid growth with headline figures for revenues and profits consistently increasing.

This is off the back of a rapid expansion in the sportswear market in China, which is expected to achieve annual growth rates of around 10% both in 2019 and 2020, according to Statista, a business-intelligence portal. Anta in 2018 reported revenues of RMB 24.1 billion, up 44.4% over 2017 .

In 2009, Anta bought the rights to the FILA trademark for mainland China, Hong Kong and Macao. The acquisition is a crucial part of the surge in its mainland China business, with an increase in revenues of 79.9% versus just 18.3% for Anta-branded products. FILA-branded goods now account for more than half of the company’s gross profit.

“To some extent, it [FILA] is still seen as a cheaper alternative to Adidas and Nike, but Anta has been working hard to create more of an image of a first-choice brand and has been fairly aggressive with its marketing,” says Ben Cavender, principal at China Market Research Group. “It has also used brands like FILA to try and move up-market and into street wear.” Financially, the latter strategy seems to be successful.

FILA is not the only foreign company Anta is using to fuel growth. In 2019, Anta purchased the Finnish company Amer Sports for $5.2 billion, bringing into the fold brands such as Arc’teryx and Wilson.

Another key part of the company’s strategy has been building sales through brand attachment via sponsorships that extend beyond local Chinese teams and sport stars to include names such as Filipino boxer Manny Pacquiao and Klay Thompson of the NBA.

The race is on

But the first obstacle to Anta’s global ambitions may not be Adidas and Nike but other Chinese brands, in particular Li-Ning, named after the athlete who became a gymnast star at the 1984 Summer Olympics in Los Angeles.

“First of all, Li Ning himself is a celebrity, a well-known sportsman who has won several Olympic medals,” says Haru, an online fashion commentator who blogs under the name Haruru. “This is something Anta could never compete with.”

He goes on to note that Li-Ning scored a big hit with its range unveiled at the 2018 New York Fashion Week and has garnered considerable street-cred for its cool clothing designs with a modern Chinese feel. Anta today could be seen as being where Li-Ning was around the time of the 2008 Beijing Olympics, of which Li-Ning was a sponsor, although Li-Ning’s efforts to capitalize on that event backfired.

“Li-Ning is an interesting case because going back five years, Li-Ning over-expanded its retail footprint in China and tried too hard to copy Nike,” says Cavender. “The Li-Ning of 2019 is in a much stronger place. It has embraced being a Chinese brand with unique Chinese design characteristics and has been setting the internet on fire with its street wear.”

He notes how Li-Ning had to scale back and re-evaluate before achieving a resurgence. Thanks to those efforts, the company is now booming with profits in the first half of 2019 nearly tripling. Its rise has been reflected in Li-Ning’s share price, which has risen around 170% since June 2018, compared to just over 50% for Anta.

Michael Norris, strategy and research manager at AgencyChina, a market intelligence firm, says that although Anta is currently more financially successful, it is Li-Ning that seems to epitomize the concept of “Cool China.” “By contrast, Anta’s products look and feel more functional,” says Norris. Cavender adds, “Anta is seen as a strong option. Still not the first choice for many, but it is definitely now viewed as a quality alternative to foreign brands.”

Relay race

Most sportswear companies rely on their own brand, but Anta stands out for its multi-brand approach. Along with the acquisition and licensing agreements already mentioned Anta also has a joint venture with Itochu for the Descente brand, and in 2019 it gained a family of brands from its Amer purchase.

“The multi-brand strategy also brings a growing reputation to Anta,” says Dai. “FILA keeps its 80% year-on-year growth rate, and other brands like Descente and Kolon are all running successfully in China.”

The multi-brand strategy has helped grow Anta’s bottom line, even though it also risks overshadowing the Anta brand itself in the market. Until the Amer Group purchase, Anta was largely dependent on the home market, but with several international brands now under the group’s control, it can make bigger forays into overseas markets. The multi-brand strategy has also allowed the company to target different market segments. “Anta is building up their brand matrix, from entry-level sports goods to premium outdoor and ski brands as well as sports equipment from the Amer Group,” says Dai.

The China-US trade war, and in particular a Chinese backlash against the NBA in late 2019 related to a politically charged tweet, have helped strengthen Chinese sportswear brands and manufacturers in their home market. This has come at a time of growing national pride and a greater willingness amongst consumers to support local brands.

“Both Anta and Li-Ning have been beneficiaries of the Guochao (national tide) trend,” says Norris. “Chinese consumers have responded positively to domestic sportswear brands aggressively adopting streetwear influences, while playing up local themes like folklore references or printing “Öйú” (China) in large characters.” He believes that Anta’s association with the 2022 Beijing Winter Olympics will, in the short term, help the company to further capitalize on this trend.

“Anta has understood how nationalism can benefit them,” says Thomas from S2M. “They’ve positioned themselves strongly toward domestic athletes, national teams and now as an Olympic sponsor. They’re focusing on where there is relevance to their marketing in China because most of their market is currently domestic.”

He notes that purchases by Chinese consumers of sportswear are largely not about using the clothing for sport but are more aspirational. Shifts in Chinese society toward more active and leisure-focused lifestyles have helped build the market for this type of clothing.

While Anta’s official sales growth figures have been phenomenal, some market observers, including several short-seller research firms, have identified potential problems in its reported financials. “The numbers behind Anta’s growth story have been questioned,” says Norris. “Blue Orca, GMT Research and Muddy Waters have each published research interrogating Anta’s financial statements.”

It is to some extent unclear how the two brands, Anta and FILA, balance the two company’s accounts. FILA is certainly much more visible in the market, especially in first-tier cities. “I think the answer is one of scale,” says Thomas. “FILA is a genuine global brand, whereas Anta is still pretty much restricted to Chinese domestic markets. Most of their [Anta’s] global growth will come from acquisition rather than the organic growth of the Anta brand itself.”

Running the world

Anta is aiming to be not just a competitor to Adidas and Nike at home but also around the world, but few Chinese companies have so far managed to make the jump to become globally competitive. One of the only ones to have done it organically is Huawei while most others, including Bytedance, Geely and Lenovo, have done it via acquisitions. In many ways, Anta’s approach is like that of automaker Geely, which buys existing brands and operates them as separate entities.

“Outside the core brand, Anta’s overseas acquisitions may prove more successful in winning over European and North American consumers than a fully-fledged market entry,” says Norris.

Achieving success internationally as well as domestically also has to do with corporate management. According to Thomas, part of the reason Li-Ning failed in its first attempt to go global was that it tried to do too much too quickly without the product lines and quality to support it. Anta, he believes, is in a far better position now than Li-Ning then.

“What (Anta founder) Ding Shizhong understood is that you may have a good idea or concept but you need the right people in your business to run it,” says Thomas. “And he has employed a lot of very good, competent seasoned professionals in this market.” One notable early appointment was James Zheng, who formerly ran Reebok’s China operations, as president in 2008.

The finishing post

Although Anta seems to have positioned itself well, there are still many hurdles ahead to achieve global success. The company is likely to benefit in the run-up to the next Winter Olympics, but it needs to be careful not to repeat the mistakes of Li-Ning and make sure it masters the mainland China market first. “Companies like Nike are effectively marketing organizations that happen to sell shoes, so it is very difficult for an outsider to break into that top position in the market,” says Cavender, noting that it may take some time for Anta to be in a position to compete globally.

Through acquisitions, the company has made far greater inroads into the overseas sportswear markets than its Chinese competitors without having to bear the associated marketing costs of trying to take the Anta brand itself global. Tempering the future success of this approach is also the increasingly stringent Chinese government controls on overseas acquisitions above $50 million. However, Anta’s Amer Group purchase was subject to these controls and was approved, and so these restrictions may not be unsurmountable.

There is now already some knowledge of the Anta brand overseas thanks to sponsorship of athletes like Klay Thompson, but many of these deals, such as with his associated KT shoe line, have been about riding the popularity of the NBA with Chinese fans. The recent NBA tweet issue shows that such associations can be problematic for a Chinese sports brand, both at home and abroad.

Anta has a plan and they have the determination but getting into the lead position is not going to be easy for two main reasons—the general global perception of Chinese products as being low-quality goods and the deep consumer loyalties attached to Adidas and Nike.

If Anta’s ambitions of becoming a global household name are to be realized, it is going to be a long road. “They’re not ready for it yet, maybe in five to 10 years’ time,” says Thomas. “First, they don’t have the revenue to get one of the marquee athletes. Adidas and Nike have so much more to spend, and secondly they don’t have the distribution channels to benefit from it.”