Agriculture in China is still primitive and needs to be modernized quickly. But whose responsibility is that?

Wang Liang is a farmer in the northeast province of Heilongjiang, China’s top corn producer. Despite fertile soil, Wang says the small size of his plot limits his crop yield and income. Both took a hit last year when unseasonably cool spring weather delayed planting by two weeks.

“It’s not that my situation is bad, I just don’t earn very much money,” Wang says. “It’s the same for all of us here.”

Farmers like Wang are straining to feed China’s 1.3 billion people and the country’s export markets on just 7% of the world’s arable land. Urbanization further threatens capacity, as Beijing aims to move 100 million people from rural to urban areas by 2020. To meet expected food consumption needs that year, China must boost grain output by 10% over current levels, according to a 2013 Ernst and Young report.

Beijing recognizes the agricultural sector must be brought up to speed with developed nations, but the prevalence of small, fragmented land plots and unproductive farms render that task daunting. Further confounding the process is Chinese law, allowing farmers usage rights but not ownership, effectively cutting farmers out of the lucrative land deals engineered by local officials via a “collective ownership” scheme.

Despite those obstacles, reforms are underway. To begin, Beijing is creating a registration system that will record farmers’ ownership of their land and allow them to transfer usage rights. It also plans to professionalize the agriculture sector by training large numbers of farmers in modern agribusiness.

Foreign investment seems a likely antidote to stalled agricultural development, but China’s leadership sees food independence as a national security issue and chafes at the prospect of reliance on multinational companies to feed its own population, no matter how advanced their technology, hindering the role that such investment could play. That leaves the best prospects for agricultural modernization in the hands of domestic tech companies, private-equity firms and agribusiness entrepreneurs.

The Last Modernization

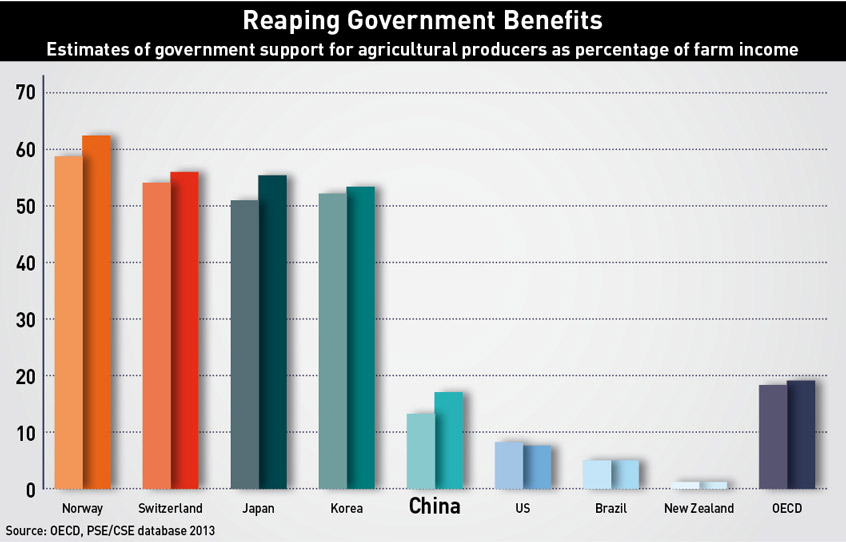

While China produces nearly one quarter of the world’s food, its agriculture industry is primitive, 108 years behind the US and 36 years behind South Korea, says the Chinese Academy of Social Sciences.

Agriculture contributes just 15% to China’s GDP, despite providing jobs to more than one third of its labor force. Compared to China’s manufacturing and services sectors which drew in $38 billion and $50 billion in foreign direct investment (FDI) respectively last year, agriculture, animal husbandry and fishery businesses attracted just $1.4 billion.

But for certain investors, Chinese agriculture offers opportunity. Singapore-based CMIA Capital Partners is raising $150 million for a private-equity fund that will invest in Chinese agribusiness. The cross border China-Israel fund Infinity is also investing in agriculture, backing firms operating in Beijing Eco-Valley, a newly established agriculture park in the capital.

Scale-up activity is already happening in the dairy industry. According to a Rabobank report published in October 2013, the focus on milk quality in China since 2008—that year, milk and milk products tainted with the industrial chemical melamine killed at least four babies and poisoned thousands more—has favored the rise of large-scale dairy farms. The share of production of farms, with more than 500 cows, grew rapidly from 17% of total milk production in 2008 to 27% in 2011. “KKR [a large US private-equity firm] did well in Modern Dairy. There is a view that this is how to make money,” says David Mahon, who heads a Beijing-based investment management firm active in China agribusiness.

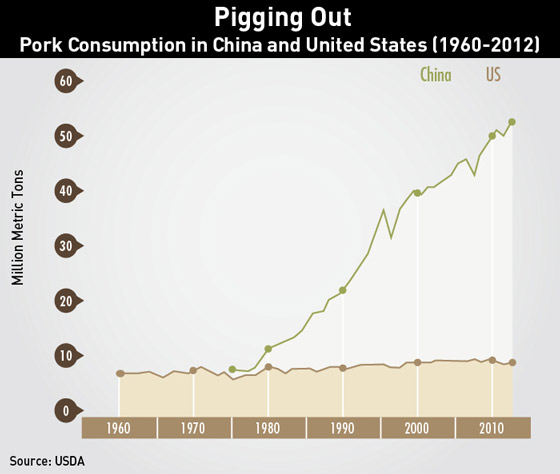

Pig farming is also scaling up, as Beijing seeks to curb rising prices in the world’s largest pork market. The Jiahua Pig Breeding Farm in Zhejiang province, which raises 100,000 pigs a year, is one of the largest new industrial hog farms. In the future, China aims to source 80% of its pork from scaled-up farms that produce at least 500 pigs annually.

For now, massive agribusinesses like Jiahua comprise just 2% of China’s hog farms and 40% of its pork is still produced on small backyard farms. Most Chinese rural households each till about half a hectare, an area roughly the size of an American football field, sub-divided into five or more separate plots. The prevalence of these small, fragmented plots presents one of the biggest challenges to bringing China agribusiness up to first-world standards.

The Farm-Town Blues

China’s current agricultural system does not provide farmers with the income necessary to spur productivity, nor does it encourage the development of skills needed in modern agribusiness.

Small land plots are one reason for that, preventing farmers from generating significant profits for themselves or investors, says Ma Wenfeng, an analyst at China Agribusiness Orient Consultants in Beijing. “It’s a bad cycle,” he says. “Farmers earn just enough to get by and have no spare income to invest in education that could boost their productivity or know-how.”

The productivity issues are evident in the most ubiquitous crops and products. The current per-hectare yield of soybean and corn in the US is double that of China, while cows in the US, which in some instances are scientifically bred, produce four times as much milk on average as those in China.

The fragmentation of rural land also inhibits scale. “Farmers are free to rent land and build scale, but it is not easy to put together a large, contiguous plot because land is so fragmented,” says Bryan Lohmar, China Country Director of the US Grains Council. “Plots are different in every village.”

And while private-equity firms like CMIA may be bullish on China’s agribusiness potential, concerns around fraudulent accounting may be stymieing the capital that could otherwise alleviate some of the farmers’ income pressure.

“It’s very hard to verify what is and isn’t there,” says Mahon. The hog producer AgFeed is a case in point. Filing for bankruptcy in July 2013, AgFeed acknowledged “fictitious sales” logged between 2008 and 2011 and is alleged to have underreported revenue figures of divisions for sale by tens of millions of dollars between 2008 and 2010.

Restrictions on foreign investment in the agriculture sector, which Beijing classifies as a “strategic industry”, further hobble efforts to scale up. For instance, regulations prohibit foreign firms from producing genetically modified crop seeds in-country and only allow them to produce non-modified seeds in a joint venture in which the Chinese party is the controlling shareholder.

“China is walking a razor’s edge on this,” says Fred Gale, a senior economics researcher at the US Department of Agriculture. “They are afraid their own seed industry will die on the vine if multinationals have free reign because their technology is so far ahead, but they know they need the best technology to increase productivity.”

But before the seed industry can blossom, farmers need reassurance that their land rights won’t be completely negated on the whim of local officials that sniff a lucrative business deal. Despite improvements on the issue of land grabs, disagreements between farmers and officials still weaken development opportunities.

Facing tough conditions, younger farmers are increasingly opting to work in cities, where personal incomes are three times those in the countryside. According to the National Bureau of Statistics, China’s rural population dropped by 12.61 million to 629.61 million as of the end of 2013.

“Farmers are more willing to buy a truck and be a trader than buy a tractor and be a farmer,” Lohmar says.

The farmers themselves remain largely unskilled, presenting another major challenge to strengthening Chinese agribusiness.

Sliver Linings

In a bid to professionalize farming practices, the Ministry of Agriculture announced in August last year the construction of farmer-training bases in 100 counties. The bases are expected to train 100,000 professional farmers over the next three years. Some of them may be urban residents with the aspiration to operate a farm as a business.

“Nobody educated would have wanted to go to the countryside as recently as five years ago,” says Gale of the US Department of Agriculture. “That meant being a bumpkin.” But he feels that stigma is fading.

Beijing is also encouraging farmers to “franchise” their lands to large farming entities, farmers’cooperatives and agricultural enterprises. According to Agriculture Minister Han Changfu, China will commence land registration in more areas in 2014, aiming to roll out the scheme nationwide in 2015 and complete it within five years.

“Many farmers do not trust the current system to guarantee their land rights, so they hesitate to rent their land out,” says Ruan Wei, a senior economics researcher at the Norinchukin Institute in Tokyo. Once farmers feel more secure that their land will not be reappropriated against their will, they will be more likely to rent it out, which will boost their incomes, she adds.

Improved ownership clarity and structure augurs promise from investors, particularly from newly interested technology firms. Joyvio, a subsidiary of the Lenovo parent Legend Holdings established in 2012, has become China’s biggest producer and distributor of blueberries and kiwi fruit in less than two years following its acquisitions of existing fruit companies in China and Chile. The company has said it aims to implement global standards and to make farmers more cognizant of food safety issues. Joyvio says it is even mulling the use of IT systems to monitor farmer activity.

“That was a smart move,” Mahon says of Joyvio’s acquisitions. “They bought proven producers of kiwis and blueberries, which are fruits with some of the highest profit margins.” Their antioxidant properties make them popular with Chinese consumers, and in the case of blueberries, a reputation as a potent aphrodisiac, Mahon says. “That’s a high selling point”.

But other tech firms’ forays into agriculture have yet to flourish. The IT firm NetEase, which earns most of its revenue from internet gaming, released a statement last month explaining why the pig farm it launched in 2012 had progressed less than expected. “Agriculture is a brand new field for NetEase, and managing a complicated supply chain is not what an internet company is good at,” the statement said. The initial plan announced in 2009 was to set up a farm that would raise 6,000 to 10,000 pigs annually with a target opening date in 2012. As of December 2013, the farm was still in an experimental stage and had only raised 400 pigs with 100 head nearly ready for slaughter.

Farms of the Future

Investment from the tech sector plays into Beijing’s overall strategy to reboot farming in China with a new set of actors, capital and concepts, says Gale of the US Department of Agriculture, but will take decades to come to fruition. “As NetEase found out, agriculture is a long-term and very complex process that is harder than setting up a website,” he says.

Meanwhile, land reform will be slow coming, says Ruan Wei of the Norinchukin Institute in Tokyo. Local governments rely on land sales to boost GDP, “one of the most important criteria for evaluation by Beijing”, she says.

And in spite of the land grabs, some farmers have bought into the idea of collective ownership. A survey conducted last year by John Donaldson and Forrest Zhang, professors at the Singapore Management University, found support for China’s current land system among rural Chinese households in Fujian, Heilongjiang, Henan, Shandong and Yunnan. According to their research, most farmers believe state ownership is “more egalitarian than private ownership.”

A more immediate problem for Chinese farming is the disappearance of arable land and corresponding spike in agriculture imports. The widening rift between China’s 95% grain self-sufficiency target and the actual rate of less than 90% prompted the central government to pledge in December that China would follow “a national food security strategy based on domestic supply and moderate imports.”

Yet that goal may well prove elusive. China would need an additional 40 million hectares of arable land—almost 25% of the existing total—to grow sufficient crops to replace imported volumes, according to the Australian Farm Institute. Pollution is a major part of the problem. Vice Minister of Land and Resources Wang Shiyuan told reporters at a recent press conference that some 3.33 million hectares of China’s farmland—an area as large as Belgium— is too polluted to grow crops.

The Safety Net

Since Beijing sees investing in agribusiness as “a kind of social responsibility”, domestic investors can expect high-level backing, including favorable lending terms from the China Development Bank, Mahon says. In a nod to Chinese consumer preference for foreign goods, Heilongjiang-based Beidahuang Group reached a deal to develop 300,000 hectares of land for farming in southern Argentina in 2011. Entrepreneur Zhang Renwu is now China’s largest alfalfa supplier, sourcing the crop from two farms he purchased in Utah.

In Mahon’s view, Chinese policymakers face a dilemma: consumer demand for foreign food products outstrips that for those made in China, but Beijing must still safeguard the interests of its own farmers. Chinese consumer confidence in domestic agriculture and the government’s ability to regulate it was badly shaken by the 2008 melamine scandal in the dairy industry and has yet to recover, he says.

In that sense, opportunities remain for foreign firms in China agribusiness “It can be done, but China has to be seen as not compromising its own domestic industry,” says Mahon. “The smart thing [as a foreign investor] is to say let me build five hog farms and an abattoir, which is classified as industrial and can be taxed,” he says. “There you have a strong story, you have integrated value.”