By Dr. Li Haitao, Dean’s Distinguished Chair Professor of Finance, Associate Dean for Chinese MBA, Cheung Kong Graduate School of Business

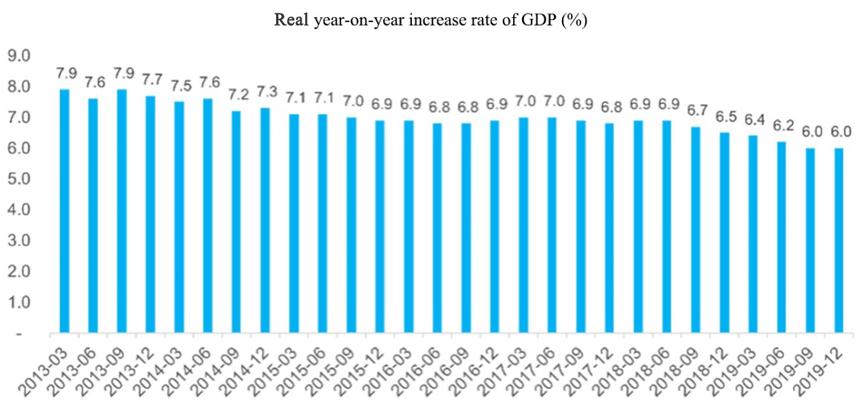

In 2019, China’s economy seemed stable, but encountered headwinds. According to China’s National Bureau of Statistics, China’s real GDP growth in 2019 was 6.1%, 0.6 percentage point lower than the previous year. Economic growth showed a quarter-on-quarter downward trend, dropping to 6.0% in the third quarter of 2019, just within the 6.0 to 6.5% target range set by the government for the year.

Chart 1: Steady Decline of Domestic Economic Growth in 2019

The three major drivers of China’s economic growth – consumption, investment, and net trade – all performed poorly in 2019.

Consumption growth continued to slow moderately, with total retail sales of consumer goods up by 8.0% year-on-year in 2019, one percentage point lower than in the previous year. Data showed that the decline in automobile consumption, which had contributed most to overall consumption, slowed, reducing from -2.4% year-on-year in 2018 to -0.8%. Real estate investment was resilient, while manufacturing investment dropped sharply, with fixed-asset investment, previously China’s major engine of growth, rising by 5.4% year-on-year, 0.5 percentage point lower than the previous year. While real estate industry regulations have not been loosened, investment in the industry has maintained unexpected resilience, with year-on-year growth of 9.9%, up 0.4 percentage point on the previous year. Impacted by the counter-cyclical policies, infrastructure investment rose by 3.3% year-on-year, up 1.5 percentage points from the previous year. Manufacturing investment rose by only 3.1% year-on-year, 6.4 percentage points lower than the previous year, impacting the performance of total investment.

Foreign trade was the biggest drag on the economy, with USD import-export volumes down by 1.0% year-on-year in 2019, reflecting growth of 0.5% in exports and a 2.7% fall in imports.

In fact, China’s economy started to slow down in the second half of 2018. On top of a falling total factor productivity caused by demographic change, financial deleveraging and the China-US trade war have also added short-term downward pressure on growth.

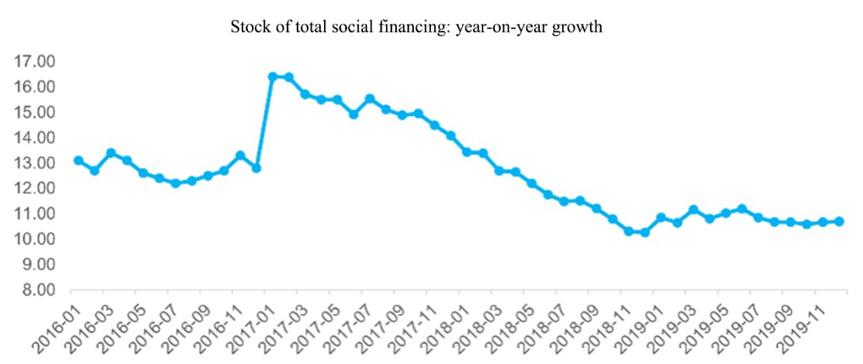

The financial deleveraging policies in new asset management regulations have lowered growth in social financing, tightening financial conditions. In November 2017, the People’s Bank of China, China Banking Regulatory Commission, China Securities Regulatory Commission, China Insurance Regulatory Commission and State Administration of Foreign Exchange jointly issued a draft of new regulations on asset management. These 29 new regulations clarified and unified regulatory standards in response to problems related to asset management in various financial institutions, including irregular business development, regulatory arbitrage, multi-layer nesting of products, rigid redemption terms, evasion of financial supervision and macro-control. The release of the draft initiated a financial deleveraging; growth in total social financing balance declined to 10.3% in December 2018 from 14.5% in November 2017

Based on historical data, the year-on-year growth of total social financing balance is an immediate indicator of real economic growth. Once financial policies are tightened, nominal GDP growth tends to slow within 2-3 quarters. Thus the decline in economic growth since 2018 can be viewed as a result of the tightening financial conditions caused by financial deleveraging.

Chart 2: Decline in Growth of Social Financing Balance from Q4 2017

In March 2018, after initiating a seven-month trade investigation by Section 301 of the Trade Act of 1974, U.S. President Donald Trump signed a memorandum to impose an additional 25% tariffs on a range of high-end manufactured imports from China, including the aerospace, information technology, high-speed rail and new energy vehicle sectors. This marked the beginning of the China-US trade frictions. Since then, China and the US have imposed punitive tariffs on each other several times. Weak external demand caused by the rising tariff rates has also affected investment, employment and consumption and even triggered the discussion of the relocation of manufacturing industries. Manufacturing investment therefore also decreased.

At the beginning of 2020, many positive signals suggest that China’ economy will be able to maintain relatively stable high growth during the year.

A fine-tuning of monetary and fiscal policies allowed finance to expand again in early 2019. Since the first cut in the reserve requirement ratio at the end of March 2018, the People’s Bank of China made further 250 basis points (bp) and 150 bp cuts respectively in 2018 and 2019. On January 1, 2020, it announced a 0.5 percentage point cut in the reserve requirement ratio effective as of January 6, representing an injection of more than RMB 800 billion into the economy. In terms of fiscal policy, the central government implemented multiple rounds of tax and fee cuts in 2019. For example, in early 2019, the tax burden on micro and small companies was significantly eased, and six special additional deductions were introduced to individual income tax. In April, the government reduced the tax rate of its value-added tax and increased the tax deduction, easing the tax burdens for individuals and companies, especially for micro and small companies. Meanwhile, fiscal policy remained expansionary by increasing the local special debt. Reflecting this policy mix, year-on-year growth of total social financing balance reached a turning point in early 2019 at 10.7%, 0.7 percentage point higher than 2018.

Furthermore, after several rounds of consultations, China and the US finally concluded the phase-one economic and trade agreement, signed by Chinese Vice Premier Liu He and US President Donald Trump on January 15 2020, which should ease pressure on external demand. China committed to purchasing and importing no less than USD 200 billion of manufactures, agricultural and energy products and services in 2020 and 2021. The US committed to halving additional tariffs on USD 120 billion of Chinese goods to 7.5% from February 14. The two sides also reached a preliminary agreement on strengthening intellectual property protection, further opening up the financial sector and bolstering macroeconomic policy and exchange rate coordination. While China-US trade friction remains a perennial problem, this agreement should significantly ease pressure on Chinese growth due to the weak external demand in the short term, and increase exports and domestic manufacturing investment.

The COVID-19 outbreak presents the major threat to China’s economic growth in 2020. Identified as a public health emergency of international concern on January 30 by the World Health Organization, this epidemic continues to spread, and has impacted demand for goods and services in sectors including food and beverages, tourism and entertainment during the peak Spring Festival season. Continued spread of the epidemic is also likely to affect the resumption of industrial production after the holiday. But we think this will have a limited impact on China’s overall economic growth, since the government will implement offsetting supportive fiscal policy, and if the epidemic lasts, accommodative monetary and industrial policies should be sufficient to stabilize economic growth.

Thus, in 2020, we believe that China has numerous highlights to look forward to, in the fields of finance, consumer goods, manufacturing and technology.

Financial reform: still underway

Reform of China’s financial system passed a milestone in 2017, when a range of far-reaching financial market reforms were implemented by regulators. But in 2020, China’s financial system reform still remains “underway”, with continued calls to “crack hard cases” and focus on deepening the internal reform and scaling up the external opening-up.

Since 2012, China’s financial industry regulators have focused on financial innovation and liberalization. For example, the securities industry has held a series of innovation conferences, continually promoting innovation in multiple areas of business, and improving the industry leverage. Taking trust companies as representative of diversified financial institutions, they have rapidly grown into the economy’s major financing channel, given their advantage of having authorized licenses.

But this wave of financial liberalization is now creating potential risks. For example, the de facto mixed operation model adopted by commercial banks, China’s most important financial intermediary, converts large amounts of assets into off-balance sheet items using trust, asset management security, and investment fund subsidiaries, fueling the continued rapid growth of so-called “shadow banking”. This business model essentially involves non-bank financial institutions exploiting their licenses and differences between various regulators’ supervisory regimes to engage in cross-market regulatory arbitrage, allowing banks to circumvent supervisory restrictions on capital. But these shadow banks accumulate excessively high hidden leverage, and once the risks embedded in these off-balance sheet assets start to rise, their parent banks will bear the resulting losses, creating risks that are systemic to the entire financial system.

Chinese policy makers have been expressing concern regarding financial market risks since the end of 2016, further prioritizing mitigation of this risk at the 2019 Central Economic Working Conference. Overall policy underwent great changes in 2017, when “prevention and mitigation of major risks” was acknowledged as a priority among the “three tough battles” identified by Chinese president Xi Jinping in the Report of the 19th CPC National Congress. At the National Finance Working Conference in July, China decided to establish the Financial Stability and Development Committee, the highest coordinating and regulatory agency, under the State Council, which builds on the previous framework of separated operation and supervision to provide a regulatory mechanism for industries, eliminating cross-market regulatory arbitrage. In 2017, numerous financial supervision measures were introduced, most far-reaching of which was November’s exposure draft for new regulations in asset management, which heralded the beginning of China’s era of financial deleveraging.

Between 2018 and 2019, various types of risks affecting China’s financial system emerged. In the early days, when financial conditions were tightened, smaller manufacturers, especially those with little clout in the overall financial system, would be first to feel pressure, creating default risk. According to incomplete statistics, over 150 bond issuers on inter-bank markets and exchanges defaulted in 2019, involving capital of nearly RMB 120 billion (roughly USD 17.2 billion). Among them, around 40 bond issuers defaulted for the first time in the bond market. The distribution of defaults suggests that, due to various characteristics of China’s financial system, the tendency for private enterprises to default has yet to substantially improve. The soft budget constraints facing large state-owned enterprises and local governments leave private enterprises with only marginal access to financial resources; when overall financial conditions tighten, they are the first to suffer.

Risks continue to emerge in the financial industry in 2019, leading to the joint announcement of the takeover of Baoshang Bank, a medium-sized city commercial bank, by the People’s Bank of China and the China Banking and Insurance Regulatory Commission in May, an indication of these policymakers’ determination to contain these risks.

How will China’s financial system reform and opening-up continue in 2020? What important measures will be taken? We think China will focus on issues such as the integration of the dual tracks of the interest rate system, defusing financial risks, deepening capital market reform and promoting the opening-up of China’s financial markets.

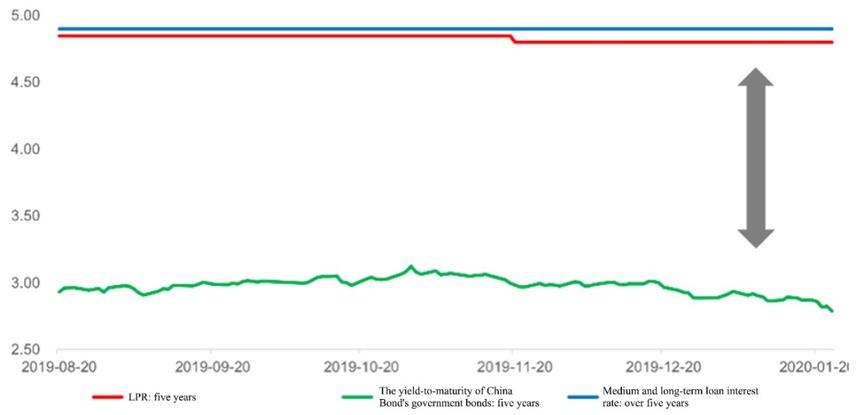

The central bank has been continuously cutting the reserve requirement ratio since 2018, which we expect will be more clearly reflected in pricing in 2020. That is, transmission channels for capital prices will be opened as the dual tracks of the interest rate system are integrated, reducing the real economy’s costs of financing. In fact, the “necessity of researching and introducing a benchmark loan rate switching scheme” was pointed out as early as Q3 in the 2019 China Monetary Policy Implementation Report. On December 28, the central bank made a formal announcement that the benchmark for loans using the existing floating rate would be converted to LPR, in a process beginning March 1, 2020, and completed by August 31. This switch to LPR should promote flexibility in the linkage between official and market interest rates, lowering the interest rates faced by the real economy.

Chart 3: Differences between Official and Market Interest Rates

Once implementation of new asset management regulations are completed in 2020, it is expected that existing assets will be handled more flexibly. The central bank’s 2019 China Financial Stability Report stipulated that 2019 would seek to prevent and defuse financial risks and 2020 would address the roots of the financial risks. Some small and medium-sized financial institutions may face less financial risks, but approaches to the disposal of risks are likely to be varied and market-oriented, with institutions such as toxic asset management companies expected to play an increasingly important role. We believe that the establishment of the higher level coordination and regulatory mechanism for mixed industry management now leaves very little room for financial institutions to conduct cross-market arbitrage and the pressure for off balance sheet assets to shrink to normal in future still remains.

2020 will be the first year of “full openness” for China’s financial markets. According to the Opinions of the State Council on More Effectively Using Foreign Investment, issued in November 2020, China will shorten the approval time on the operations of foreign-controlled businesses, and allow foreign entities to own up to 51% shareholdings on securities, funds, futures and life insurance joint ventures. We have already seen that some leading global financial institutions were issued shareholding licenses. Thus, from 2020, Chinese financial institutions will be competing directly with global their peers, and should consider whether their years of experience in the Chinese market will enable them to compete and attract customers with better products and services.

Consumption upgrading: an unstoppable trend

Rapid growth of disposable income has given the Chinese population increasingly strong purchasing powers for high-end consumer goods and services, as growth in the domestic luxury market and Chinese tourists’ overseas travel consumption clearly reveals.

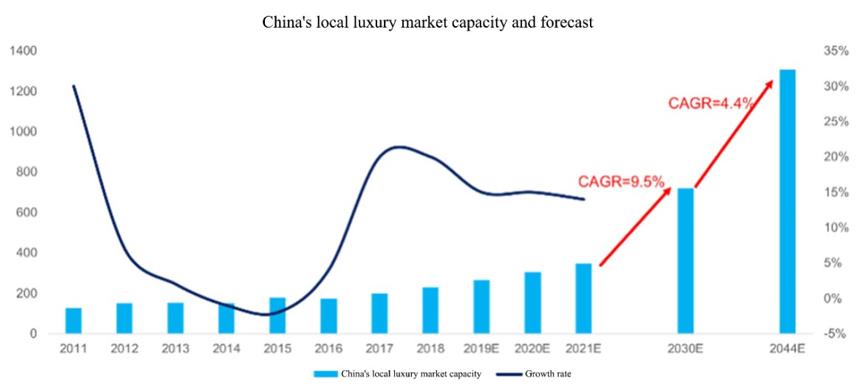

According to Bain & Company, China’s overall luxury market was worth about 23 billion euros in 2018, and will sustain a compound annual growth (CAGR) of 9-10% until 2030. Major global luxury brands have successively entered the Chinese market since the 1990s and China now represents one of the most important luxury markets worldwide.

Chart 4: China’s Domestic Luxury Market Set for 9-10% CAGR

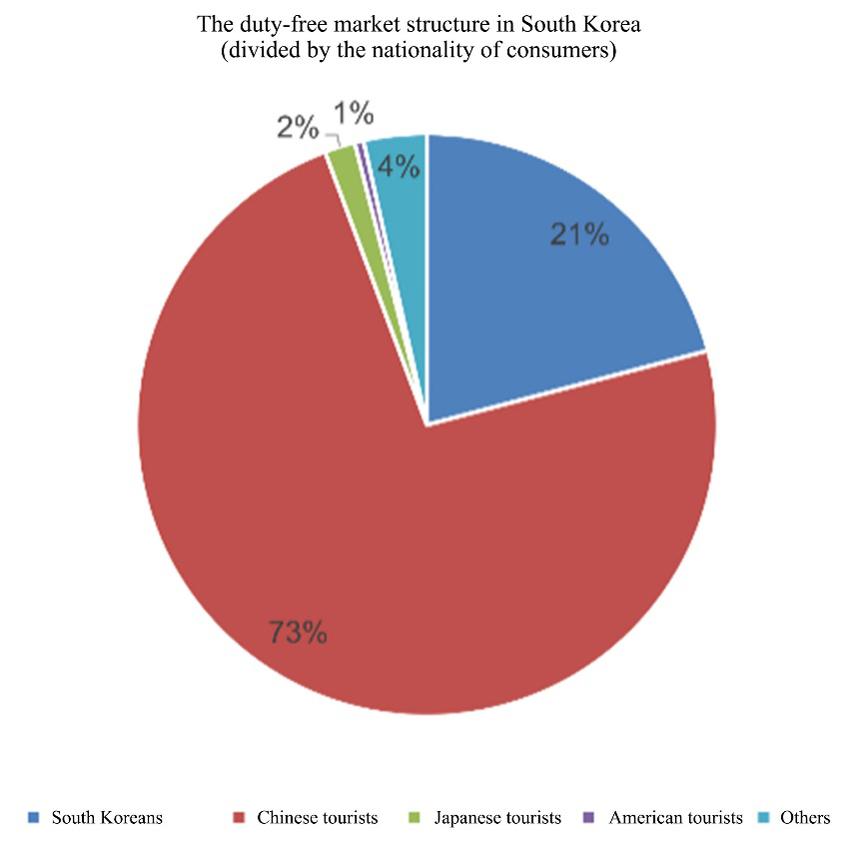

The purchasing power for high-end consumer goods for the Chinese is also reflected in their consumption while travelling. Broken down by consumers’ nationality, Chinese luxury consumption accounted for 25% of the world total in 2012, increasing to 32% in 2018 to surpassing the United States’ 22%. China has thus become the most important luxury market in the world. According to Nielsen 2017 data, Chinese tourists’ per capita consumer spending on overseas shopping was USD 762, 1.6 times that of non-Chinese tourists. Statistics from relevant South Korean government departments indicate that Chinese have become the largest consumers in the South Korean duty-free market, spending a total of over RMB 80 billion in 2018, and accounting for 73.4%.

Chart 5: Dominance of Chinese Tourists in South Korean Duty-free Market

In addition to pursuing global luxury goods, the Chinese are also avid consumers of domestic luxury brands. Moutai, the luxury brand with the highest cultural recognition in China, has increased its retail price to RMB 2,000-3,000 per bottle, surpassing prices for even the most famous European and American spirits. The stock price of Kweichow Moutai, an A-share listed company producing the Moutai Liquor, surged tenfold over the past decade, achieving the fourth highest market capitalization on the Shanghai and Shenzhen exchanges, and surpassing long-established European alcoholic beverages company Diageo as the world’s new “king of liquor”.

Reflecting a sustained high economic growth, China’s per capita GDP exceeded USD 10,000 in 2019, another major achievement. According to China’s National Bureau of Statistics, China’s GDP in 2019 was RMB 99.0865 trillion, 6.1% higher than the previous year, with per capita GDP exceeding USD 10,000, at USD 10,276, based on the annual average exchange rate. Chinese services consumption should now begin to rise steadily: in other markets, when per capita GDP has exceeded USD 10,000, consumption patterns have rapidly shifted away from goods towards education, culture, entertainment, medical care and other services, and from consumption of staples towards discretionary consumption.

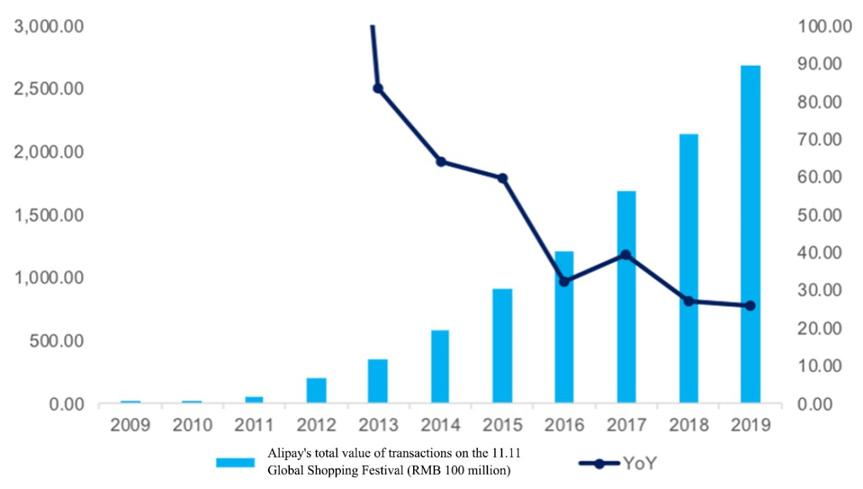

Chinese residents’ overall spending power should not be underestimated: the e-commerce sector was still capable of achieving year-on-year growth exceeding 20% from an already-high base in 2019, and the total value of transactions increasing 25.7% year-on-year during that year’s 11.11 Global Shopping Festival, to reach RMB 268.4 billion.

Chart 6: Increase of Singles Day Transactions by 25.7% year-on-year to RMB 268.4 Billion

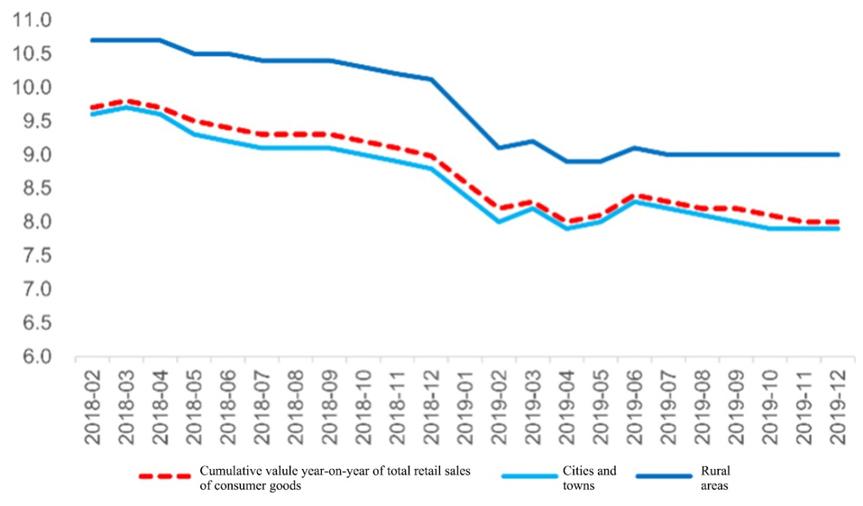

Increasing disposable personal income is driving rapid growth in the consumption capability of residents in China’s lower-tier cities and rural areas. According to official statistics, growth of consumer goods retail sales in rural areas reached 9.0% in 2019, continuing to outpace urban areas. Pinduoduo, which champions mass consumption in China, is competing in an e-commerce market highly monopolized by giants such as Alibaba’s Taobao and JD.com with some success, via its unique customer targeting and pricing strategies, acquiring customers via official WeChat accounts and mini programs, and an emphasis on “ultra low prices” and “group buying”. According to JIGUANG Big Data, in 2018, nearly 65% of Pinduoduo users were from third- and lower-tier cities; Pinduoduo’s rise can be seen as a close reflection of increasing national purchasing power.

Chart 7: Growth of Sales in Rural Consumer Goods Outstrip Urban Areas

China’s consumer market is also seeing the presence of innovative business models. In high-end consumption, duty-free channels are attracting customers back from their previous overseas consumption. As for the mass consumption, new models such as e-commerce live-streaming and social influencer marketing have helped revive brands that otherwise lacked marketing channels.

The flourishing of the tourism market for Chinese consumption raises concerns that China’s high import taxes may be the major factor driving this consumption outflow. But in addition, relatively low purchase frequencies for luxuries in emerging Asian market, leads overseas brands to tend to set higher prices for Asia than for European and American markets. Bain statistics indicate that 73% of Chinese luxury consumption occurs outside China. But we think that this situation is changing. As Chinese consumers become more important than before in the global luxury market, European and American brands have begun to equalize their Asian market pricing. More importantly, China’s duty-free consumption channel is developing rapidly, and set to continue its expansion and reinvigoration, as measures including further easing of offshore duty-free policies and the establishment of more inbound duty free shops are introduced.

Since 2017-18, major Internet platforms have adopted a “content + special offers” strategy which has consistently attracted users, and influencers who are followed by millions of fans online have become opinion leaders of the new era. Survey data attests to the great purchasing power of these fans. Having already exploited monetization via advertising and tipping, major online influencers have set their sights on e-commerce. Their live-streaming emerging as a new force during the 2019 Singles Day, the world’s largest online shopping event. More than 50% of online stores participating in live-streaming events increased their profits, contributing to an increase in the aggregate transaction value to nearly RMB 20 billion. Social influencer marketing has increased more rapidly in consumer subsectors where this channel has greater influence. For example, by over 90% in the food sector and over 80% for beauty products.

Advanced manufacturing: forging ahead

After years of uninterrupted development, “Made in China” has undoubtedly contributed to China’s reputation. Despite ongoing concerns over outward relocation of manufacturing due to the escalation of China-US trade frictions, China still offers a manufacturing solution that is second to none.

This is evident in the manufacturing of mobile phones. Under pressure from rising labor costs and punitive tariffs levied by overseas markets, Foxconn, Xiaomi, Huawei and other enterprises have established Indian and Brazilian factories to balance their portfolios, but with disappointing results. Indeed, while mobile phone suppliers began moving to India in 2017, a complete mobile phone supply chain has yet to be established there. Although the Indian government hoped that cell phone companies would drive development of local suppliers, shortages of skilled workers, low productivity and poor quality have led to continued reliance on components and raw materials imported from China, and after tariffs, India-produced cell phones are more expensive than imported ones. Brazil too has failed to impress. Before Foxconn’s factory in Brazil began operating, it was predicted that prices for iPads and iPhones would drop by as much as 30% due to tariff reductions and exemptions. But their final prices remain nearly double those of the United States, primarily because of poor quality in production technology, which has inflated overall production costs.

An examination of China’s manufacturing sectors reveals that the value added of technology-intensive industries, such as pharmaceuticals, electronics and special equipment, is growing faster than that of capital and labor-intensive manufacturing industries, such as steel and textiles. This, coupled with years of industrial upgrading, reflects the Chinese manufacturing industry is “big but not strong”, in comparison with the United States, Japan, Germany and other manufacturing heavyweights. For example, while Chinese enterprises lead in manufacturing computer and other electronic equipment by market share, their profit margins remain much lower than those in the United States and Japan, suggesting that they continue to focus on low value-added sections on the industrial chains.

In September 2018, the prominent Japanese business weekly Toyo Keizai compared Chinese and Japanese competitiveness across 50 fields and found that while China surpassed Japan in smartphones, AI, new-energy automobiles and fintech, Japan remained ahead in established manufacturing industries including robotics and industrial machinery, high-speed railways, medical robots and automobiles. As further industrial policies are implemented, China’s advanced manufacturing upgrading should continue, with financial support for advanced manufacturing enterprises from domestic capital markets in particular, expected to contribute to accelerating this upgrading. But more importantly, Chinese enterprises must increase their R&D investment, in order to accumulate “hard power”.

The new-energy automobile industry can be seen as a harbinger of Chinese manufacturing’s ascendancy. Benefiting from years of vigorous promotion and a series of supportive government policies including subsidies, tax exemption and right-of-way advantages, China’s new-energy automobile market has grown rapidly. According to Marklines statistics, Chinese new-energy automobiles’ sales volume increased robustly from 19,000 units in 2013 to 1.229 million units in 2018, a five-year CAGR of 130%, far exceeding the world’s 18% average over that period, which made China the world’s largest market for new-energy automobiles in 2018.

Chart 8: China’s Leading Role in New-energy Automobiles

As the Chinese new-energy automobile industry has flourished, enterprises in its industrial chain have begun to excel in international markets. Based on OEM data, 13 of the world’s top 20 best-selling new-energy vehicle models in 2018 were Chinese made, from manufacturers like BYD, Chery, BAIC, SAIC Motor and Geely. In terms of power batteries, the key link in this industrial chain, domestic Chinese enterprise CATL achieved 21.9% market share in 2018, after surpassing Japanese battery manufacturer Panasonic to become the world’s largest power battery system provider as early as 2017. BYD, another Chinese enterprise, ranked third, followed by South Korean battery manufacturers such as LG Chem and Samsung Electronics.

The new-energy automobiles sector should remain one of Chinese manufacturing’s key sectors in 2020. On January 7, 2020, Tesla’s Shanghai-based Gigafactory 3 delivered its second batch of Model 3 to customers. As Tesla’s second vehicle assembly factory after the one in California, it came on stream within a year of construction, far faster than overseas media and even Elon Musk expected. With Tesla actively participating in China’s new-energy automobile market, domestic Chinese new-energy OEMs and suppliers will need to step up their game.

Technological innovation: catching up fast

As 5G began to sweep the world in 2019, Chinese companies have continued to prove themselves, catching up quickly to their American and European peers, and even becoming global leaders in some areas. In China’s A-share market, technology was undoubtedly one of the best-performing sectors in 2019, attesting to the strength of Chinese enterprises in the 5G era.

However, looking back, scientific and independent technological innovation has not always gone smoothly in China. In the 3G era, the European-led 3GPP established and developed 3G’s WCDMA standard, which now has the highest base station coverage worldwide. And the United States established the 3GPP2 to develop the competing CDMA2000 system. While China had been able to develop its own 3G communications standard, this has lagged behind those of the US and Europe. China completed 3G spectrum allocation and issued 3G licenses in January 2009, and the three major Chinese operators carried out commercial tests in March that year. But 2009 was the year the world’s first pre-commercial 4G service was launched in Sweden. Therefore, during the 3G era, China’s communication network lagged a decade behind international leaders. However, during the 4G era, FDD-LTE and TD-LTE—LTE technologies developed and led by China based on TDD—became the major mobile communication standards, a breakthrough of increasing China’s influence on telecommunications, and reversing years of weakness in international standard setting.

Chinese enterprises are ready for the 5G era. According to IPlytics statistics, China ranks first worldwide in 5G patent applications with 34%, well ahead of South Korea’s 25%. While Huawei has invested over RMB 100 billion in R&D, ranking fifth worldwide on the 2018 EU Industrial R&D Investment Scoreboard. Hence, there are reasons to believe that China may lead the global popularization of 5G.

Through 5G, China is expected to accelerate its development of consumer and industrial applications as the 5G era makes new application scenarios possible, permitting for example faster and smoother user experiences for VR and AR-enabled consumption. China Broadcast Network has also been granted a commercial 5G license, so the radio and television industry stands to benefit from 5G upgrades to existing broadband access scenarios and mobile Internet, enabling provision of higher-quality, more attractive content through new entertainment technologies including UHDV. In industrial application scenarios, 5G networking’s peak data transmission rates run as high as 20Gbps, with users experiencing data transmission at up to 1Gbps. In addition, with air interface latency of less than 1ms, millions of connected devices per square kilometer, and movement at up to 500km per hour, can be supported. High-performance 5G networks thus can support the special requirements of industry application scenarios, and serve as infrastructure of the digital transformation in a wide variety of industries, by, for example, permitting large-scale IoT communication connectivity for far more terminals. Other application scenarios might include IoT, blockchain, smart agriculture, smart cities, energy Internet and smart homes. Ultra-reliable, low-latency communications also greatly improve the precision of communications, suiting various applications such as autonomous vehicles, smart power grids, telemedicine and industrial automation.

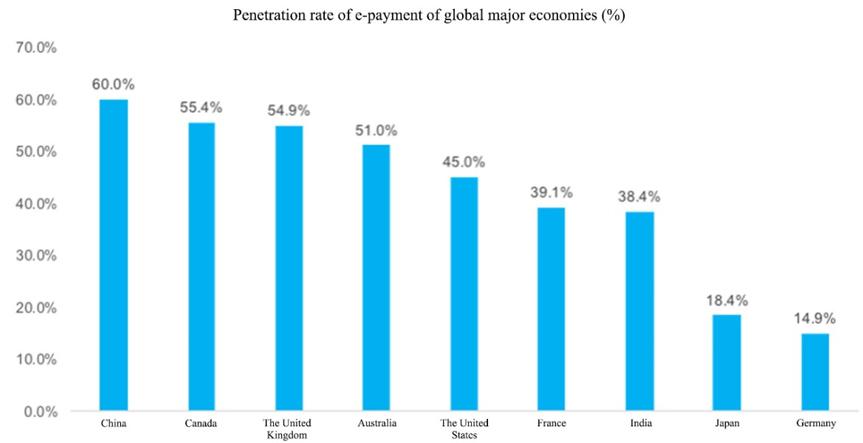

China has undoubtedly become a leader in fintech and related fields. The rapid spread of e-payment in China is supported by the continuous promotion of Internet giants such as Alibaba and Tencent and the construction of infrastructure such as QR code payment systems. According to World Bank statistics, the Chinese economy is a global leader with the highest e-payment penetration rate. Relying on payment portals, Chinese fintech giants such as Ant Financial have been engaged in innovation and iterative improvement of their products and services for around 15 years, and have already assembled a portfolio of products fulfilling many of their consumers’ financial needs, including small and micro loans, wealth management, insurance and securities trading.

Chart 9: China’s Leading Role in E-payments

China’s fintech giants have begun to share their experiences with fintech enterprises elsewhere, especially in emerging markets, and thus disseminating the notion of inclusive finance. Indeed, “globalization” was one of the three important strategies advanced by Ant Financial in December 2019. By sharing its technology and business model, Ant Financial is creating value and fulfilling innumerable emerging market consumers’ and enterprises’ digital technology needs. Through the adoption of a “technology export + partnership” model, Alipay has established nine local “Alipay” applications in India, Pakistan, Bangladesh, Thailand, Philippines, Malaysia, Indonesia, South Korea and Hong Kong, most of which have become locals’ preferred e-payment method. With investment and support from Alipay, Paytm, an Indian e-commerce payment system, has become the fourth largest e-payment worldwide, with users growing from less than 30 million in 2015, at the beginning of the partnership, to over 400 million at present. Chinese fintech giants are set to continue driving innovation and evolution in their industry, as consumer service technology continues to develop and the concept of inclusive finance deepens.

But we must note that many Chinese industries that have failed to invest adequately in R&D in the past, and enterprises lacking innovative technologies, are often the first to fall victim to dramatic changes in their industries. The pharmaceutical and automobile industries are two such examples.

The pharmaceutical industry is strongly affected by its regulatory environment. Because the new drug approval process in China is very time-consuming, and patent protection for new drugs is very strict, Chinese pharmaceutical enterprises prefer to sell generic drugs as their prices are high, thus discouraging the incentive to invest in R&D. In addition, the structure of medicine sales in China is distorted, with many layers of added prices between pharmaceutical factories and hospitals. This has formed “grey” areas on the profit chains, which for many years, have encouraged Chinese pharmaceutical enterprises to “emphasize sales over R&D”. However, a series of changes in policies since 2018, for example targeting quantity drug procurement, is changing the situation facing both new and generic drugs. Sharp price reductions may push generic drug manufacturers into becoming general manufacturers in the future, where only the innovative ones will be able to earn market shares with new drugs.

The automobile industry faces threats from the market opening-up. Chinese automobile enterprises seldom invest heavily in the R&D of core technologies, instead most of them copy existing car models. In 2018, President Xi Jinping relaxed restrictions on foreign ownership of manufacturing companies, including those in the automobile industry. As China gradually opens automobile enterprises to foreign investment, local automobile companies will inevitably face competition from international peers. In this environment, China’s automobile industry can only prosper by investing more in R&D or by proactively joining hands with international automobile giants.