China’s economy is facing headwinds, but is easing monetary policy going to reverse the momentum?

For many China analysts, that seems to be evitable: gross domestic product (GDP) only grew by 7.3% in the third quarter, the slowest rate since the global financial crisis; the official manufacturing purchasing managers index (PMI) was at a five-month low in October, and a flash reading of the index in November by HSBC stands at a new low of 50.0.

But will easing monetary policy solve the problem of sluggish growth? The answer is a clear “no”, says Gan Jie, Professor of Economics at the Cheung Kong Graduate School of Business. According to ‘A Report on China’s Industrial Economy’, Gan’s survey of 2,015 industrial firms conducted in October, only 3% of all firms included “financing” as one of the constraining factors for their fourth-quarter production. Instead, the most common concern, shared by 63% of firms, is “lack of orders”. “Financing is clearly not a bottleneck for growth in the industrial sector,” Gan says.

The survey results make sense if one looks at the bigger picture: despite a series of targeted credit easing, China’s newly added bank loans have been stagnant since July compared with the same period last year; monthly total social financing figures have been significantly lower than those for the same period in 2013.

According to the survey, only 10% respondents said they borrowed new loans in the third quarter, and 88% said that they didn’t have the need for capital. In the past two months, People’s Bank of China (PBOC), the country’s central bank, has pumped more than RMB 769 billion into the banking system through mid-term lending facility operations, but given the industrial firms’ low appetite for capital, enhanced liquidity alone is unlikely to induce healthy expansions.

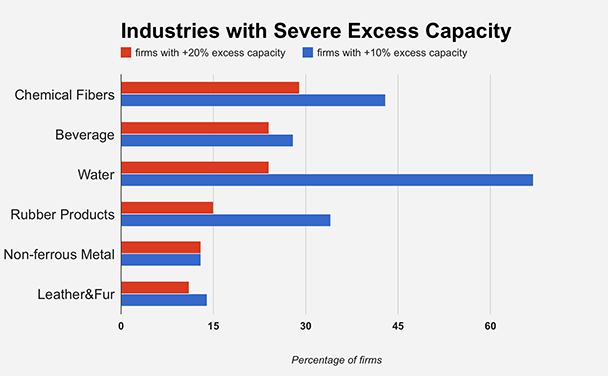

On the other hand, weak demand has caused excessive capacity for nearly half of the firms (49%) in the third quarter, according to the survey. Forty six pecent of the firms reported that supply exceeded demand in their domestic market, higher than the 42% percentage recorded in an earlier survey done by Gan in July and August.

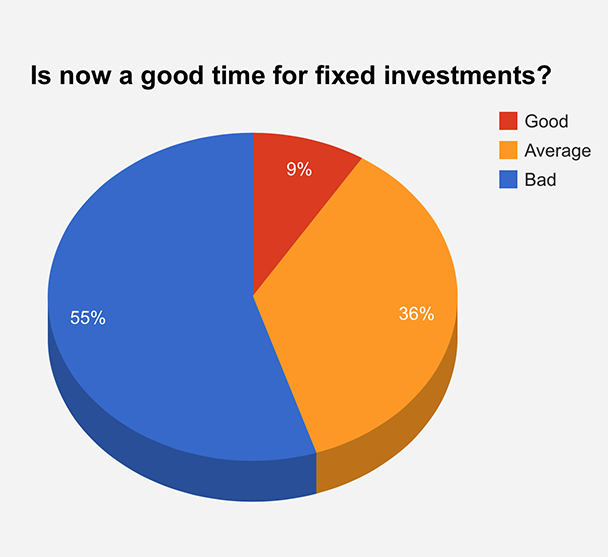

A comparison between the diffusion indices for overcapacity in the second and third quarter showed that the situation is worsening for capital goods and intermediate goods producers, according to the survey, reflecting that firms hesitated to make new investment to expand their businesses.

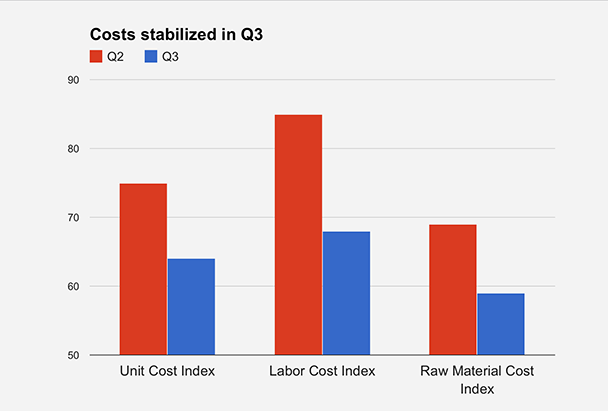

Another reason for firms’ reluctance to invest is rising costs and thin margins—37% of firms reported higher labor costs and 24% said raw material costs went up. Although cost increase stabilized relative to the previous quarter, output prices did not go up due to anemic demand. Average price index stood at 51, meaning that firms were unable to raise product prices to reflect increasing costs.

To help absorb excessive capacity, Beijing is encouraging infrastructure construction, especially railway projects. In the past few weeks, the National Development and Reform Commission, the country’s top economic planner, has approved projects to build eight new railroads, which are worth RMB 350 billion in total.

However, a spending binge is far from a long-term solution, says Gan Jie. “In the short term, it [infrastructure spending] will help [boost industrial demand], but it’s important that the money is spent on the things you actually need,” she said. She adds that she believes that there might be good opportunities for China to participate in infrastructure development in its neighboring nations, a subject vividly discussed during the recent Asian-Pacific Economic Cooperation meetings in Beijing. About two weeks prior to the meetings, 21 countries signed a memorandum in Beijing agreeing to establish an Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank, in which China will take the lead and invest $50 billion.

Another determinant of China’s industrial need is real estate, which has been undergoing a major correction since the beginning of 2014. Home prices in major Chinese cities continued to fall year on year in October, but the speed at which prices are dropping has slowed.

Gan says that the warming up of real estate would help absorb demand and spur growth, but the “golden age” of the sector has gone. “The key [for the market] is location,” says Gan, who believes that housing prices may remain resilient in first-tier cities, but not so much in third and fourth-tier cities. “I wouldn’t bet on real estate to save the Chinese economy.”