Bulls, bears and dragons

Despite a recent rule change, there are still concerns over the ability to access money in Chinese investments

In November 2021, China launched a new stock market to provide an opportunity for the country’s small companies to raise money through public listings, but trading of 10 of the stocks on that first day had to be suspended due to overwhelming demand, with one stock surging by a whopping 494%.

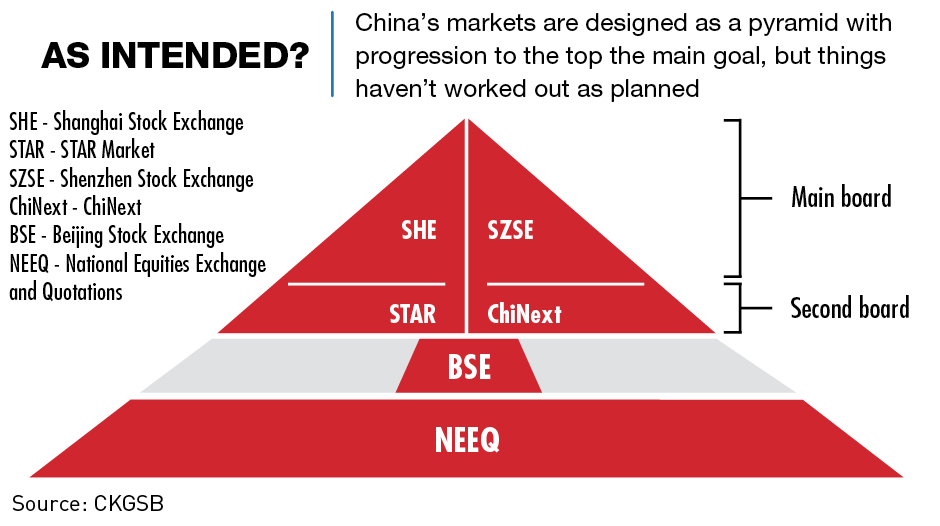

The Beijing Stock Exchange (BSE) was launched to act as a stepping stone for low-value Chinese businesses on their way from non-listed status to a potential initial public offering (IPO) on one of the country’s larger exchanges.

But with just 169 companies listed on the board, the BSE hasn’t caught on in the way that it was hoped, despite offering a less rigorous listing process, less control on share price movements and better access for foreign investment than the more regulated exchanges of Shanghai and Shenzhen. For China, with its highly-centrally-controlled system, emulating the flexible market-driven exchanges in the West is not an easy process.

Upgrading the structure of China’s markets is particularly important now that Chinese companies are under increasing pressure to list domestically, as the country tightens restrictions on overseas listings and businesses listed abroad face increased scrutiny from regulators. But the underlying central control, and the concerns it raises particuarly for foreign investors, inevitably inhibits the future international competitiveness of the Chinese markets.

“China has learned a lot of lessons from the West in terms of markets and the country’s markets are in many ways successful,” says Fraser Howie, author and China analyst. “But the overriding requirement of control by the authorities is a factor that will continue to limit their development.”

Taking stock

Securities trading in China dates back to the 19th Century, with the first stock exchange established in Shanghai in 1891. All markets were closed after the Communist Party took power in 1949, but today’s Shanghai Stock Exchange was launched in 1990. China’s capital markets have come a long way since then.

“There’s been an acceleration over the past few decades,” says Thomas Gatley, a China strategist at Gavekal Dragonomics in Beijing. “Equities have turned from being a side-show, a casino, into something operating at a vast scale.”

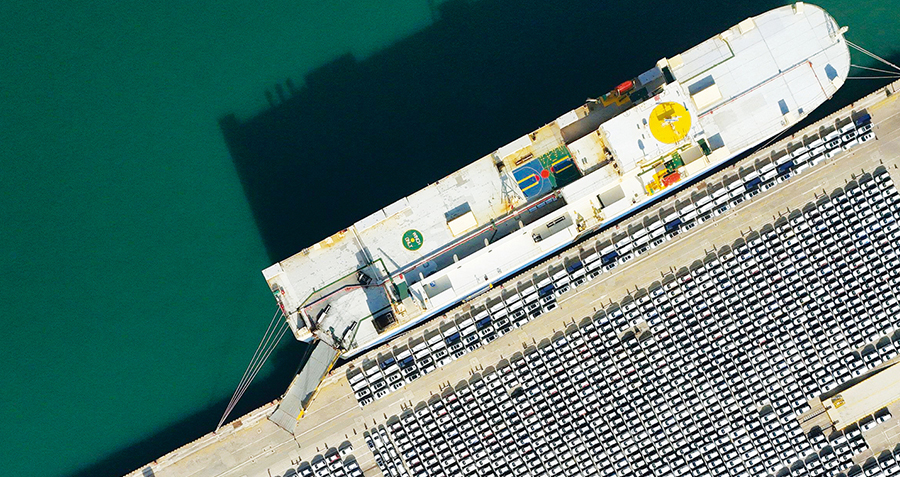

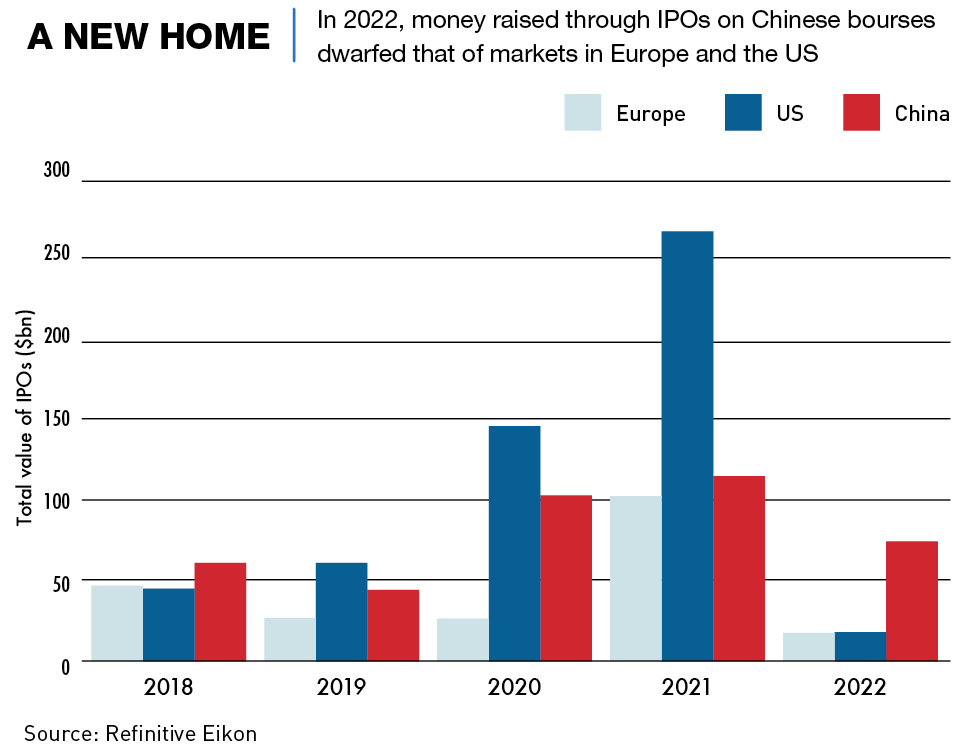

The Shanghai Stock Exchange now ranks third in the world by total company market capitalization, behind only the New York and NASDAQ markets. And in 2022, the Shanghai and Shenzhen bourses became the world’s first- and second-largest destinations for IPOs in terms of funds raised, thanks in large part to the government’s domestic listing push.

“[China] has been developing and improving its multi-level capital market system, with the total market value continuing to grow and market activities maintaining a high level over the past 30 years,” says Nelly Su, leader of the China Capital Markets Advisory Group at KPMG.

There are three mainland entities in the Chinese stock market system—the Shanghai Stock Exchange (SSE), Shenzhen Stock Exchange (SZSE) and the National Equities Exchange and Quotation (NEEQ)—plus the Hong Kong Stock Exchange (HKEX).

The Shanghai and Shenzhen markets are mainland China’s oldest and largest bourses, mainly serving companies in traditional sectors like manufacturing, energy and property. By February 2023, the SSE had listed 1,676 companies on its main board, with a total market capitalization of ¥46 trillion ($6.74 trillion), and in 2019, it also launched a subsidiary board, the STAR Market. Designed to serve the country’s burgeoning tech sector, the STAR is now home to companies with an overall market value of around ¥6 trillion ($890 billion).

Similarly, the SZSE has around 1,500 companies listed on its main board, and a tech-focused subsidiary board called the ChiNext Market. ChiNext was set up in 2009 and is about double the size of the STAR Market.

The third mainland entity, NEEQ, is an exchange for over-the-counter trading of stocks in smaller ‘public limited companies,’ and is seen as something of an entry-level system for smaller companies to raise capital prior to listing on one of the larger bourses. The SME-focused BSE, operated by NEEQ, is the mainland’s smallest bourse, with just 169 companies listed and a total market value of ¥240.63 billion ($35.3 billion).

The HKEX is the largest of the Chinese exchanges in terms of the number of listed companies, topping 2,250, and is also the seventh-largest market in the world in terms of market capitalization. It also has the advantage of being a truly international market, with many Chinese companies holding dual-listed status on the HKEX and another Western bourse. The exchange is also often used as a tool for Chinese companies to receive the benefits of foreign investment, through the round-tripping of funds through Hong Kong back into the mainland market.

Financial functions

China’s markets, although growing at a rapid pace, function somewhat differently from those in other areas of the world, with heavy state influence on exchanges, as well as stringent limitations on the movement of money.

Chinese firms seeking to list on the Shanghai or Shenzhen exchanges have always required individual approval, but draft measures released in February 2023 will remove this requirement. Many Chinese companies also struggle to meet the three-year profitability targets required to be eligible for an IPO. These exchanges also impose share price movement limits to curb market volatility: generally, stock prices cannot rise or fall more than 10% in a day, 20% for firms traded on ChiNext.

“Chinese markets are shaped by the government’s broader strategic priorities,” says Gatley. “In other large markets in the world, the choice of who is allowed to list and the way in which investors engage with valuations and picking winners and losers in those places is not so strongly tied to the state’s thinking.”

The state’s influence on stocks was evident during the time of China’s strict zero-COVID policy, with large market swings resulting from perceived mixed messaging from the authorities. But perhaps the most obvious impact in recent years, was the fall in Chinese tech stocks after a regulatory crackdown on the sector was launched in 2020. Fintech company Ant Group was forced to abandon its public listing, undermining confidence in the markets.

“The price movements over the last year of Alibaba, Tencent, and the other internet platforms have been completely divorced from any reality of their market position and are a function of this extremely tough regulatory environment,” says Gatley.

The large number of speculative day-traders has also always amplified volatility in Chinese markets, especially as trading is dominated by reactions to sudden government announcements and the preference for more liquid and explosive stocks. “Because of capital controls, there’s a large amount of trapped domestic money that chases whatever return story is attractive at the time,” says Douglas Arner, professor specializing in economic and financial law at the University of Hong Kong.

Open for business?

There are also barriers for foreign investors looking to buy and sell Chinese stocks. Historically, purchasing stocks has been difficult—unlike the freely-accessible stocks on Western bourses—and the fact that the renminbi is not fully convertible, has meant that foreign investors have had to be cautious.

“There is no argument that China’s stock markets are now huge, yet they still remain somewhat separate from global financial flows,” says Howie. “But access is now possible.”

The various different classes of shares available in China represent companies’ ownership structure, incorporation location and the exchange it is listed on, but most importantly, their availability for purchase. A-shares, for example, are RMB-denominated stocks of companies incorporated in the Chinese mainland and listed on one of China’s stock markets, and make up the majority of shares on mainland Chinese bourses—there are over 3,600 A-share companies. A-shares are available to non-domestic investors through the Qualified Foreign Institutional Investors (QFII) or Renminbi Qualified Foreign Institutional Investors (RQFII) channels.

There are also B-shares, which are shares issued by Chinese companies that are traded in either USD or HKD on the China exchanges. These shares are available to any trader with foreign currency bank accounts. Around 35% of the shares traded in China are B-shares.

In 2014, in response to the fall in overall listed company valuations, the government introduced measures to make an investment in China stocks by both domestic and international investors more attractive. The Stock Connect scheme, which links the Hong Kong bourse with those in Shanghai and Shenzhen, has since become the main route for international investors to buy mainland securities. The scheme was expanded in December 2021, boosting the number of mainland stocks eligible for trading through the link from 1,458 to 2,516, but A-share trading through the Stock Connect scheme only accounts for about 4.3% of total trades.

The Chinese bond market has also become more accessible to foreign investors, who can trade fixed-income securities more easily and freely than ever before. One example is China’s rollout of so-called low-carbon transition bonds to fund decarbonization efforts, in 2021.

“It’s easier for a foreign investor to invest in China,” says Arner. “In the past five-to-10 years, we have seen a growing amount of institutional investment both from pension funds and social security funds, as well as mutual funds and asset managers.”

Increasing support

China has also recently shown a desire to further liberalize its capital markets, starting with some of the newer exchanges such as the STAR Market being much less heavily regulated than others—share price movements are not restricted and a company simply has to meet the conditions of the exchange to list. For Shenzhen’s ChiNext sub-board, the government has loosened rules on IPOs and scrapped previously challenging profitability requirements.

The largest change in policy will be effected as a result of a number of draft measures announced in February 2023, which will result in the approvals system for listing on the Shanghai and Shenzhen exchanges being replaced with a registration-based system. These regulations will shift the decision on company listings away from the China Securities Regulatory Commission and into the hands of exchanges themselves.

“The registration-based IPO reform marks a key milestone in China’s reform of capital markets,” says Su. “It has borrowed from international best practice in alignment with Chinese characteristics and China’s stage of development. The reform is market-oriented to create a freer market for a disclosure-based, open and transparent end-to-end IPO system.”

The overall price-to-earnings ratio of China’s stocks has fallen sharply in recent years, suggesting a lower level of investor confidence in the Chinese economy. At 13 times earnings, P/E ratios are down more than 60% on the Shanghai Composite Index from two decades ago. In comparison, the average P/E ratio for the S&P 500 is 19.

A key factor is the strict controls on the convertibility of the Chinese currency, which both inhibits foreign investors from coming into the market, but also encourages Chinese investors, restricted from exporting their cash, to pump their money into mainland bourses. “The A-share market is relatively impervious to what the rest of the world thinks about China, as it’s all domestic,” says Andy Maynard, head of equities at China Renaissance in Hong Kong.

Other measures introduced by the government in recent years to increase money flows include the removal of the $300 billion overall ceiling on total asset purchases under its Qualified Foreign Institutional Investor (QFII) scheme. That freed global investors to purchase securities without a hard limit. Restrictions on moving investment capital back out of China have also been loosened, with a three-month lockup period being scrapped.

China’s markets also received an outside boost in June 2017, when Morgan Stanley started including A-shares in their MSCI Indices. Originally with an index inclusion factor (IIF) of just 5% in the Emerging Markets index, this was increased in November 2019 when they increased the A-share IIF, and therefore investor exposure to the Chinese market, to 20%.

The MSCI move is reflective of the global equity balance, but given the level of government influence over Chinese markets, it also exposes global shareholders to the risks and unpredictability associated with government policy changes—a risk not replicated to the same degree in Western market exposures.

But without solving access issues and removing the markets from overbearing government influence, central government policy will continue to be the biggest factor in the growth and competitiveness of the country’s equity markets. “There is a view that the safest way to invest in China is to follow the sectors the government wants to support at any given point in time,” says Arner.

“From an investor perspective, the major drawback of investing in China is that the most important thing going on is what the government wants to do,” he says. “Reading the policy tea leaves is very important.”

International concerns

Confidence in Chinese securities has also been tested by concerns over the quality of audit work. US regulators threatened to delist over 200 Chinese companies from American stock markets—until they were granted the previously unheard-of permission to inspect the audits late last year, somewhat cooling the dispute.

There are also still strict rules governing access to corporate information and the disclosure of financial information outside of China. “This undermines trust in Chinese markets,” says Gatley. “For stock pickers, there are questions around corporate governance and auditing. It’s certainly not as good as elsewhere in the world.”

Arner agrees. “The key to the sustainable development of the Chinese markets is going to be improving the quality of financial information that companies produce and that investors have access to.”

Other major concerns include a swathe of geopolitical issues, including the decoupling of China from the West, as well as concerns brought on by the Russian invasion of Ukraine. Foreign investors dumped Chinese shares last year on the back of fears that Western countries would sanction Beijing if it supported Russia in the conflict.

Although the initial concerns over possible sanctions have passed, the future direction of Chinese markets are still heavily dependent on the state of US-China relations. “Prior to the trade war, the direction was pretty good,” says Gatley. “It is tough to say whether we are still on that pathway.”

Debt difficulties

Closer to home, there are concerns over the outsized role that SOEs play in the market as they control more than 56% of the corporate assets listed. Given their highly-leveraged nature—in 2016 China’s SOE liabilities equaled two-thirds of total assets—worsening economic conditions can often have a direct impact on Chinese markets. And given China’s currently slowing economy, this current market makeup could pose a threat to Chinese stocks.

“You are seeing slower growth rates across the Chinese economy and less effectiveness from additional levels of debt and leverage in generating growth in the Chinese economy,” says Arner. “It is a very strong possibility that additional debt in a more slowly growing economy is likely to result in lower performance from Chinese companies.”

However, given their SOE status, they enjoy a level of protection from the government that may make them impervious to failure. And for Maynard, he sees Chinese markets as more driven by growth stocks than SOEs. “As a contrary indicator, it may be true that SOEs are under pressure and more exposed to an economic slowdown,” says Maynard. “But I believe Chinese equities should continue to perform strongly as China’s economy re-opens.”

The number of private firms in China has quadrupled in the past decade or so, reaching 44.57 million in 2021, reflecting the grassroots dynamism inherent in the country’s economy.

Outlook so-so

China’s markets are now huge and play a significant role in China’s economy, but it’s still not settled what this role is, how they are regulated, and how they fit into the global financial structure. The extent to which the markets become less centrally controlled and more reflective of the market force-driven exchanges in the West will be determined by the play of forces pulling in two different directions: the determination of the Party to maintain strong central control vs the dynamism of markets that are set free and allowed to react to market forces.

For Su, China’s markets have a key role to play within the bounds of governmental priorities, “China is a socialist market economy, and its capital markets should play a more active role in demonstrating and implementing medium and long-term national development plans.”

But for others, the prevailing opinion is that this state control will likely hamper market development. “China’s markets have made huge progress in opening up access to allow foreign capital to invest, foreign institutions can basically access all aspects of the capital markets now according to the latest rules,” says Howie. “But government influence remains significant and even after such opening, market forces still play a limited role.”